Charting Progress IV

Fifty years of Bangladesh in charts

This post is the last in a series that shows Bangladesh’s economic evolution since liberation. The first part of the series looked at economic growth, poverty, and employment. The second part delved into the drivers of economic growth. The third was concerned with the society. The focus in this post is on macroeconomic management.

In the wake of the pandemic, many economies are experiencing inflation unseen in a generation. Particularly in the west, well supported by their governments during the pandemic through job guarantees and welfare payments, cashed up consumers are buying stuff online at record volumes. But firms are not able to meet the jacked up demand because repeated pandemic waves and lockdowns around the world are disrupting the supply chains. Inflation has been the result.

Bangladesh was, of course, created amidst supply disruptions of a colossal magnitude. The Liberation War had damaged every road, railway track, bridge and culvert, and telephone and electricity grid in the country. Production shrank by a fifth in the wake of the war. The new nation was buffeted by further debilitating shocks: first came the oil shock after the Yom Kippur War of 1973; then came the disastrous flood of 1974.

Faced with these shocks, a combination of inexperience and ineptitude —there were relatively few Bengalis in the higher echelon of Pakistani bureaucracy —and ideological inflexibility —the new government shunned advice and assistance from western donors and multilateral agencies — meant runaway inflation. Prices rose four-folds between 1972 and 1975, far higher than our neighbours in South and Southeast Asia (Chart 1).

Just pause and reflect on that for a moment. Prices of essentials, the proverbial rice-lentil-oil-salt, rose four-folds. Freedom must have tasted bittersweet for those who experienced it.

Of course, Bangladesh is not the only country to have experienced this kind of multiple-fold rise in prices in a short span of time. For example, Indonesia experienced a nearly fifty-fold rise in prices in the early 1960s, while Vietnam experienced a 650-fold rise in the late 1980s. Closer to our time, Zimbabwe and Venezuela have experienced such events.

These hyperinflationary episodes are, however, rare and reflect severe economic and political crises.

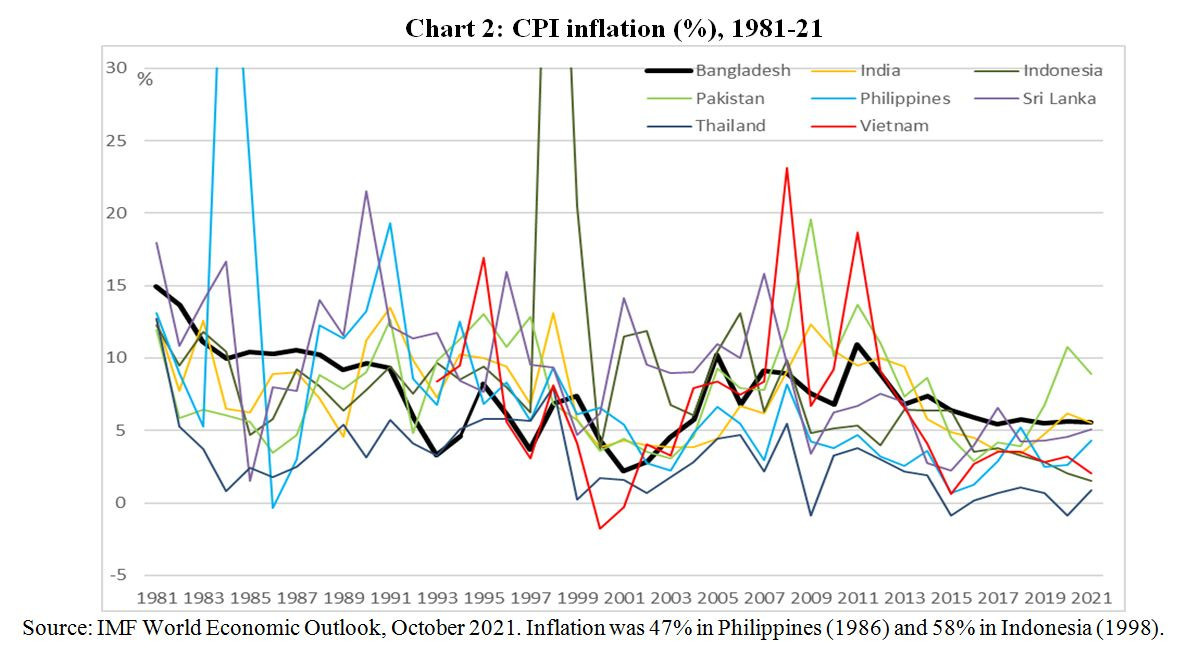

After the immediate post-war period, Bangladesh did not have any such crisis. Over the past four decades, inflation in Bangladesh had not been particularly out of line with what our neighbours had experienced (Chart 2).

It’s not that we have not been hit by disasters in these decades. For example, the 1974 flood affected nearly 53,000 square km of land. The 1988 flood was worse, affecting nearly 60,000 square km. And 1998 was even worse, with 91,000 square km of land inundated. Meanwhile, a severe tropical cyclone hit Chittagong in 1991, killing tens of thousands.

Why has the country avoided crises even in the face of worse disasters?

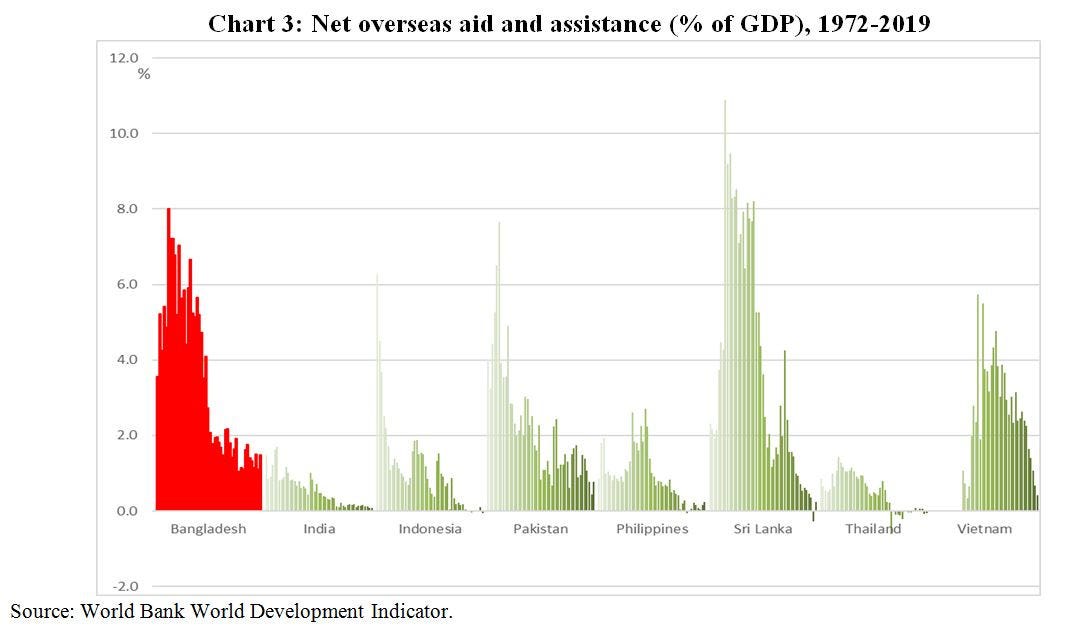

Foreign aid and assistance helped in the earlier decades. Chart 3 shows that Bangladesh receives more aid, relative to GDP, compared with our neighbours.

However, at less than 2% of GDP, foreign aid and assistance has not been as significant a factor in more recent decades.

Bangladesh has avoided economic crises, exemplified by inflationary episodes, because we have become better at disaster management, which is well understood, as well as macroeconomic management, which is perhaps less appreciated.

For developing countries, the ability to maintain exchange rate stability is a key marker of macroeconomic management. Sudden and large exchange rate depreciations are particularly disruptive in developing countries, as they make imports of essential items such as food, fuel, and capital equipment more expensive. Countries with foreign currency denominated debt are hit further with a depreciation because the debt burden rises with a cheaper currency.

Chart 4 shows major depreciation events —defined as 20% or larger depreciation against the US dollar in a year —in Bangladesh and a few selected neighbours. The taka suffered sharp depreciations in 1975, 1976, and 1982, but has avoided such a shock since then.

In fact, over the past two decades, the Bangla currency has remained relatively stable compared with those of our neighbours (Chart 5).

A sharp depreciation in the exchange rate usually means the country is unable to meet its international obligations —import bills, and repayments of loans in foreign currency.

For developing countries that manage their exchange rates (including Bangladesh and the other ones that we are looking at), foreign exchange reserves expressed as the months of imports is considered a good indicator of a country’s ability to meet international obligations. Specifically, if a country has reserves that cover less than three months of imports, it is considered to be at risk of depreciation unless corrective measures are taken.

Chart 6 shows that Bangladesh’s stock of reserves did dip below the three-months threshold in the 1980s and 1990s. But it avoided depreciation through adroit macroeconomic management. Of course, in more recent decades, the stock of reserves has been well above the threshold.

Now, one way to avoid the need to meet international obligations is to not import or borrow in foreign currency. But economic isolation of that nature is usually extremely costly in other ways. Often, imports represent key inputs into the production process of goods that are ultimately exported —Bangladesh’s readymade garment sector is an example. Further, imports force domestic producers to be more competitive, which benefits households. That is, countries that shun imports for so-called self-sufficiency end up being poorer than those that are open to international trade.

Shunning imports is a poor way to avoid an economic crisis. Acquiring foreign currency through exports, foreign direct investment, and remittances are much better. Exports and foreign investment led industrialization is a tried and tested path to economic development in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and China over the past century.

The emergence of the Bangladeshi garments industry notwithstanding, Bangladesh doesn’t export much, nor receive much foreign investment, compared with our neighbours. Relative to GDP, remittances have, however, been a more significant source of foreign currency in recent decades (Chart 7).

Public debt service burden, expressed as a percentage of foreign currency earnings, is another indicator of whether a country faces difficulty in meeting international obligations. The higher this ratio, the more the country’s foreign exchange earnings are taken up in paying down public debt. Chart 8 shows that Bangladesh is favourably placed in terms of public debt service burden.

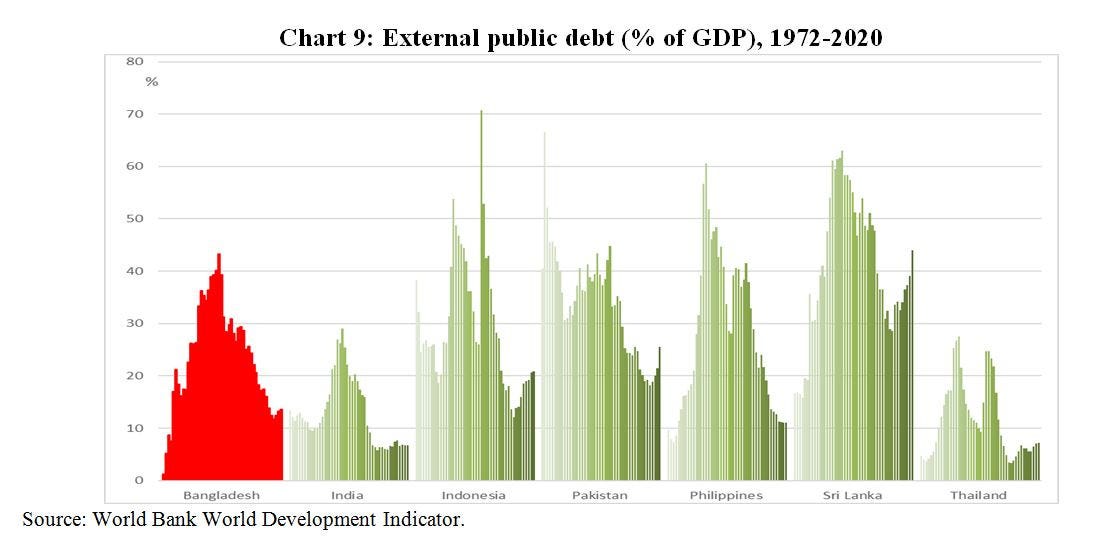

This is partly because the country’s foreign currency denominated debt has been declining relative to GDP over the recent decades (Chart 9).

Further, Chart 10 shows that the total debt-to-GDP ratio has remained relatively stable, and favourable compared with our neighbours.

That is, over the past couple of decades, successive governments have been able to manage our public finances reasonably well in the sense that the state has operated within its means. This is, however, a mixed success, because the state’s means have remained meagre. Chart 11 shows that the government collects merely a tenth of the incomes generated in the country as revenue.

Bangladesh performs much more poorly than our neighbours when it comes to domestic revenue mobilization, a situation that has not changed much in the past four decades. Whether it’s the perilous nature of the law enforcement or the dilapidated state of the public universities, a state that taxes so little is not likely to govern much, if at all.

And as a result, five decades after its birth, Bangladesh still performs poorly in cross-country risk analysis, such as the Inform Risk Index, a global risk assessment for humanitarian crises and disasters.

Chart 12 shows that it’s not that Bangladesh is more exposed to natural or man-made disasters. It’s that the country is considered more vulnerable, partly because it lacks institutions to cope with disasters.

Like the rest of the world, Bangladesh is looking down the barrel of climate change. We have proved more resilient than anyone might have expected five decades ago. However, unless the state can generate more revenue through taxes, we will remain vulnerable to a crisis.

This series was published in the Dhaka Tribune throughout 2021.