Charting Progress III

Fifty years of Bangladesh in charts

This post is the third in a series that shows Bangladesh’s economic evolution since liberation. The first part of the series looked at economic growth, poverty, and employment. The second part delved into the drivers of economic growth. The focus in this part is on the society.

At the beginning of the 1970s, with 75 million people packed in a delta the size of many small American states or smaller European countries, the then East Pakistan was described by a western journalist as a country where people are crammed in like matchsticks in a box.

Five decades on, Bangladesh has added another 90 million or so more people to its citizenry.

That’s a lot of people, but nowhere near what many demographers expected five decades ago.

Donor agencies and international organizations typically projected that the new country would see its population double before the end of the century, and perhaps add another 100‑150 million by the 2020s.

The reason there are around 165 million Bangladeshis instead of 250-300 million is because Bangladeshi women have had far fewer children over the past decades than expected by demographers.

In the early 1970s, each Bangladeshi woman had, on average, seven children. By the late 2010s, the number had dropped to two.

The decline in fertility rate was not unique to Bangladesh.

But compared with neighbouring countries, the process had started later, and the decline had been steeper —from having one of the highest fertility rates in the region, it now has one of the lowest (Chart: Fertility Rate).

One reason why women used to have many more children in the past is because many of the newborns did not survive beyond infancy.

In the then East Pakistan, of every thousand infants, around 150 perished.

By 2019, the number had dropped to almost 25.

Again, this positive development is not unique to Bangladesh. Again, Bangladesh had started later than neighbours, and is making significant progress (Chart: Infant Mortality Rate).

One key reason why children survive more than in the past is because of immunization and preventative public health measures.

For example, hardly any child aged 12-23 months was immunized for measles in the early 1980s.

By the late 2010s, most were. Again, Bangladesh wasn’t alone in achieving this feat, but it started after others and achieved relatively more (Chart: Immunisation Rate for Measles).

Not only do the children have higher survival odds, they are also expected to live far longer.

In 1971, a newborn Bangladeshi would not have been expected to see the country’s golden jubilee.

A Bangladeshi born in 2019, on the other hand, is expected to live for more than 72 years.

Again, the rise in life expectancy is not unique to Bangladesh.

But again, the process had started later in Bangladesh, and the pace of achievement has been faster (Chart 4).

One could cite other indicators of immunization or access to sanitation and so forth, but the pattern is pretty clear.

In the early 1970s, Bangladesh was a laggard in terms of health outcomes.

By the late 2010s, this was no longer the case.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, the average Bangladeshi had similar health outcomes as other countries in tropical Asia, even though the Bangladeshi earned less than half to three‑quarters of the income of their neighbours.

Macroeconomic stability allowed successive post-1975 governments to improve people’s lives.

The 165 million Bangladeshis, on average, earn three times as much as the 75 million East Pakistanis. They also live far healthier lives. This is an achievement worth celebrating.

Bangladesh’s evolution from the war-ravaged beginning to a fully-fledged developing economy has also been accompanied by significant social changes over the past five decades.

Consider, for example, where most Bangladeshis live.

For generations, the eastern Bengal delta had nurtured a rural society, its bucolic beauty celebrated in songs and poems.

In 1970, nine of ten East Pakistanis still lived in the countryside —a far higher proportion than in our neighbours. People started leaving their villages after independence.

By 2020, Bangladesh had a higher urbanization rate than India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Vietnam (Chart: Urbanisation Rate).

Towns and cities are the places of higher education, centers of governance, and investment in modern economic activities.

That’s why incomes are higher and more amenities are available in urban areas. As the saying goes, lights are brighter in big cities.

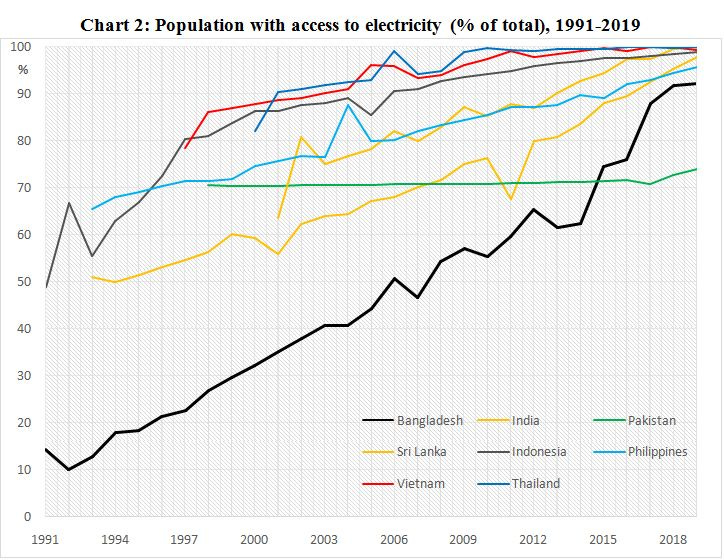

Of course, brighter lights require electricity. Even in the early 1990s, only one in every 10 Bangladeshis had access to electricity.

By 2019, nine out of ten did.

Although this is still slightly lower than most of our neighbours, the pace of electrification has been much more rapid than elsewhere in the region (Chart: Electrification Rate).

Even more remarkably, it’s not just the townsfolk that received electricity connections in the past three decades.

In 2019, 89% of the country’s rural population had access to electricity, up from less than 2% a quarter century earlier.

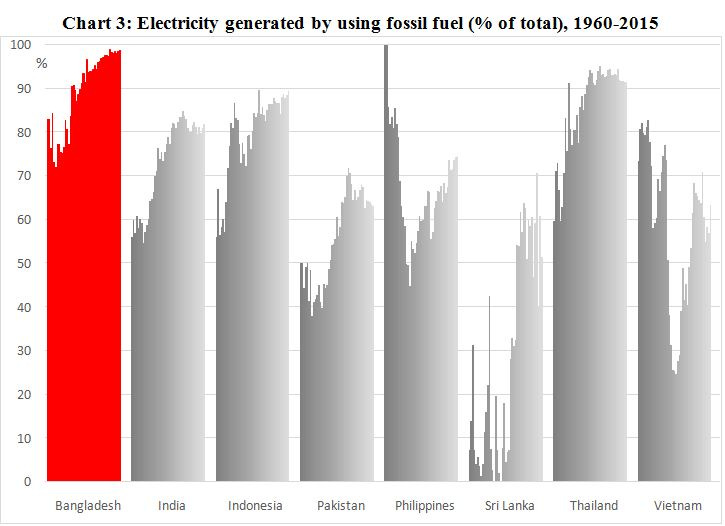

There is, however, a less positive side to this rapid electrification.

A higher proportion of electricity is generated from fossil fuels in Bangladesh than elsewhere in the region (Chart: Electricity from Fossil Fuel).

It is remarkable that a country that is one of the most vulnerable to climate change had less than 0.3% of its electricity from non-hydro renewable sources in 2015.

Also remarkable is the fact that hydroelectric sources played a relatively small role in the electrification process, generating less than 1% of the country’s electricity in 2015.

Of course, the Kaptai dam, the main source of the country’s hydroelectricity, had a far more insidious effect in terms of fomenting ethnic violence in southeastern Bangladesh.

Over the past few decades, rural Bangladeshis moved just not to the towns and cities near them, but many have also travelled across international borders and seas to work in the Gulf, Europe and elsewhere.

Remittances they send back have cushioned the country from macroeconomic shocks, and buoyed living standards of family members in the countryside.

And it is relatively less expensive to send remittances to Bangladesh (Chart: Transaction Cost of Sending Remittance).

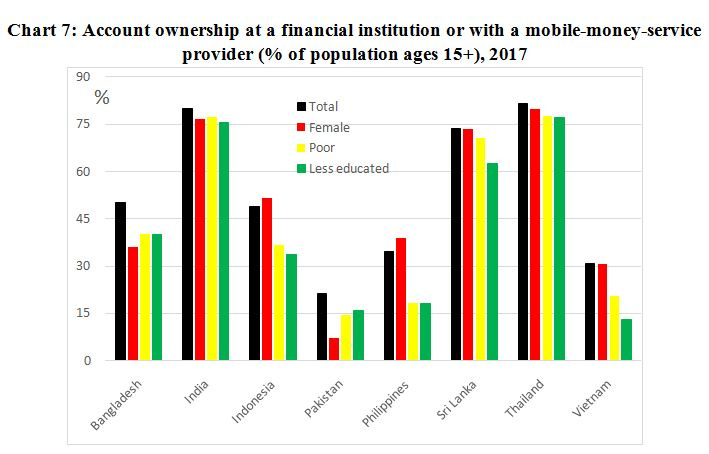

Technology has, of course, played a role in the social transformation. Mobile financial services, for example, allow individuals a range of consumption and business options that were not feasible only a few years ago.

In 2017, about half of Bangladeshis had an account with a mobile money service provider (Chart: Account with Mobile Money Providers) —more than Pakistan or Vietnam, but not as much as in India and Sri Lanka.

Crucially, even the poorer people, women, and the rural population had access to these services.

A visitor from the then East Pakistan would find modern Bangladesh completely unrecognizable. Part of that is, of course, due to global technological change.

A visitor from the then West Pakistan (or India, or any other neighbouring country for that matter) who would have returned to the country after five decades would also find a country that has transformed beyond imagination.

But it’s also worth stressing that Bangladesh is still has a long way to go. There are many aspects of life where progress has been less rapid than one might have thought.

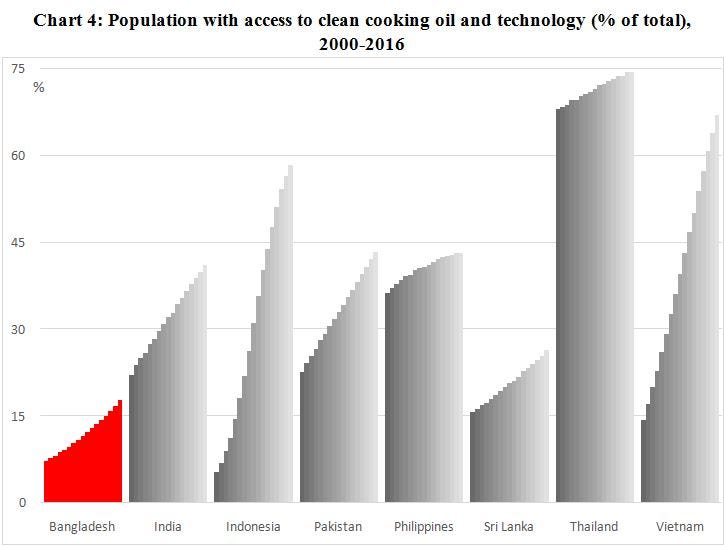

Take for example how we cook.

Less than one in five Bangladeshi had access to clean cooking oil and technology in 2016, much lower than elsewhere in monsoon Asia (Chart: Access to Clean Cooking Technology).

The rise of the country’s garments industry, employing millions of women, is well known.

But less than a third of Bangladesh’s workforce is women, whereas in Vietnam the fraction is closer to half.

One disturbing reason why Bangladesh still lags behind is because it still leads in an insidious indicator —adolescent fertility.

Shockingly, even in 2019, there were 80 births per 1,000 girls aged 15‑19 years (Chart: Adolescent Fertility Rate).

In fact, Bangladesh is not the easiest place for children (Chart: Children in Marriage and Employment).

The urbanization and electrification notwithstanding, in 2013, 5% of Bangladeshi children aged between 7 and 14 worked.

Fewer children of that age worked in India and Indonesia. And we aren’t talking about light tasks for pocket money here.

These kids toiled for 36 hours a week on average.

As bad as these factlets are, they are nowhere near as shocking as the fact that even in 2019, over 15% of Bangladeshi women aged between 20-24 had their first marriage before turning 15.

Over 15%! In India it was about 5%, in Pakistan less than 4%!

All the achievements of the past decade means little if we still expect so many children get married and raise children of their own.

As the world transitions from the COVID-19 pandemic to the so-called industrial revolution 4.0, how is Bangladesh positioned?

Not very well, judging by the paltry share of medium and high tech goods in the manufacturing exports bucket (Chart: Complex Manufacturing Exports).

One reason Bangladesh is not climbing up the value-added ladder might be because our workers are less skilled than their peers elsewhere in monsoon Asia. And it’s not hard to understand the reasons for that.

Less than a third of adult Bangladeshis were literate in 1981. The adult literacy rate rose to nearly three-quarters by 2019. But the definition of literacy here is being able to sign one’s name —hardly the stuff that will help Bangladesh become a dynamic emerging economy.

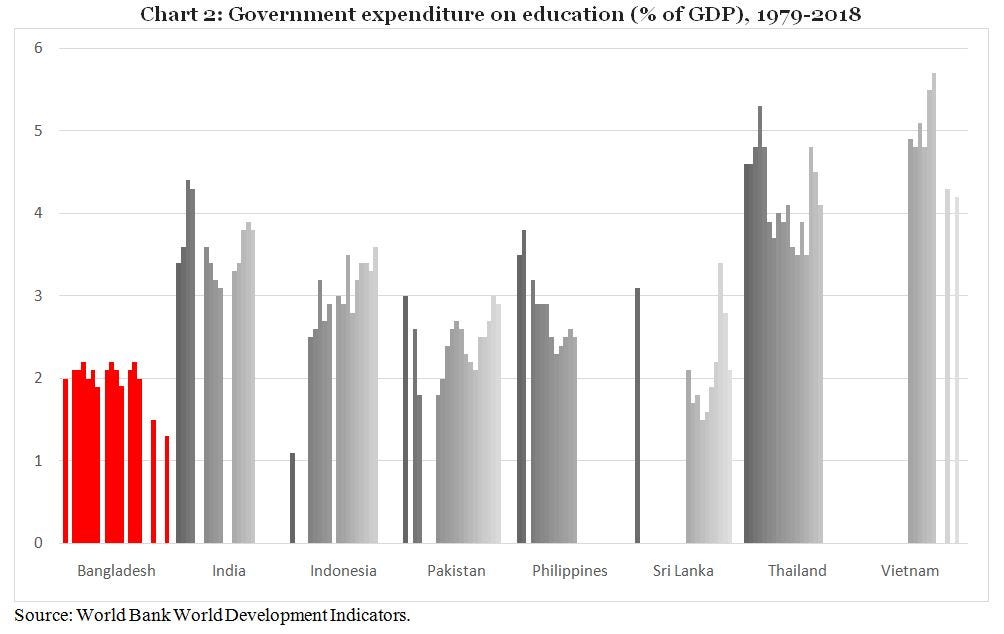

The unfortunate truth is that the Bangladesh government just does not prioritize education as much as many of our neighbours do (Chart: Government Expenditure on Education).

It’s not surprising then that each Bangladeshi primary school teacher must teach many more students than their peers in the region (Chart: Pupils per Teacher in Primary School).

This is not to say that simply increasing the expenditure on education will do. Far from it. The quality, as well as the quantum, matters. Rather, the point is that, contrary to Pink Floyd, we do need more education!

Perhaps what our workers lack in formal education, they can make up through ingenuity and self-learning. Who needs school when every Bangladeshi has access to a cell phone (Chart: Cell Phone Subscription Rate), right?

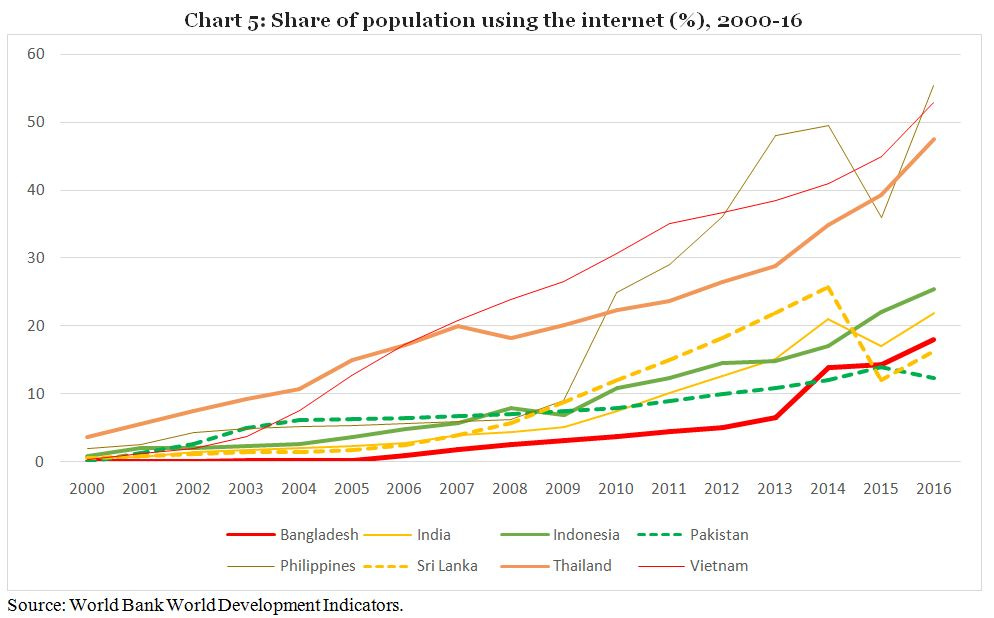

Of course, workers across the region also have access to cell phones, even more so than in Bangladesh. And more importantly, for all the hypes about a digital country, Bangladesh remains overwhelmingly offline (Chart: Share of population using the Internet).

These charts were first published in the Dhaka Tribune. All data are from the World Bank World Development Indicators.