Charting Progress II

Fifty years of Bangladesh in charts.

This post is the second in a series that shows Bangladesh’s economic evolution since liberation. Part 1 covered GDP per capita, poverty and inequality, and the labour force.

Over time and across countries, differences in living standards ultimately come down to the differences in productivity. Productivity growth in developing countries, in turn, reflect two processes: structural changes in the economy; and adoption of new technologies and better practices from more advanced economies (the so-called ‘catch up’ growth). Bangladesh has been experiencing both processes over the past few decades.

First consider the structural change. Barring the resource rich countries, sustained economic development over the past few centuries have all involved people moving from relatively less productive rural farms to higher productivity jobs in city factories. Bangladesh is no exception. Whereas two-thirds of workers tilled the farm in the early 1990s, less than two-fifths worked in agriculture by 2019. Meanwhile, industry’s share of total employment doubled to over a fifth in that time.

The transformation is also visible in terms of output (Chart 1). Whereas agriculture constituted a third of the country’s output in the early 1980s, by the late 2010s it had shrunk to about an eighth. Over the same time, industry’s share had risen from about a fifth to a third.

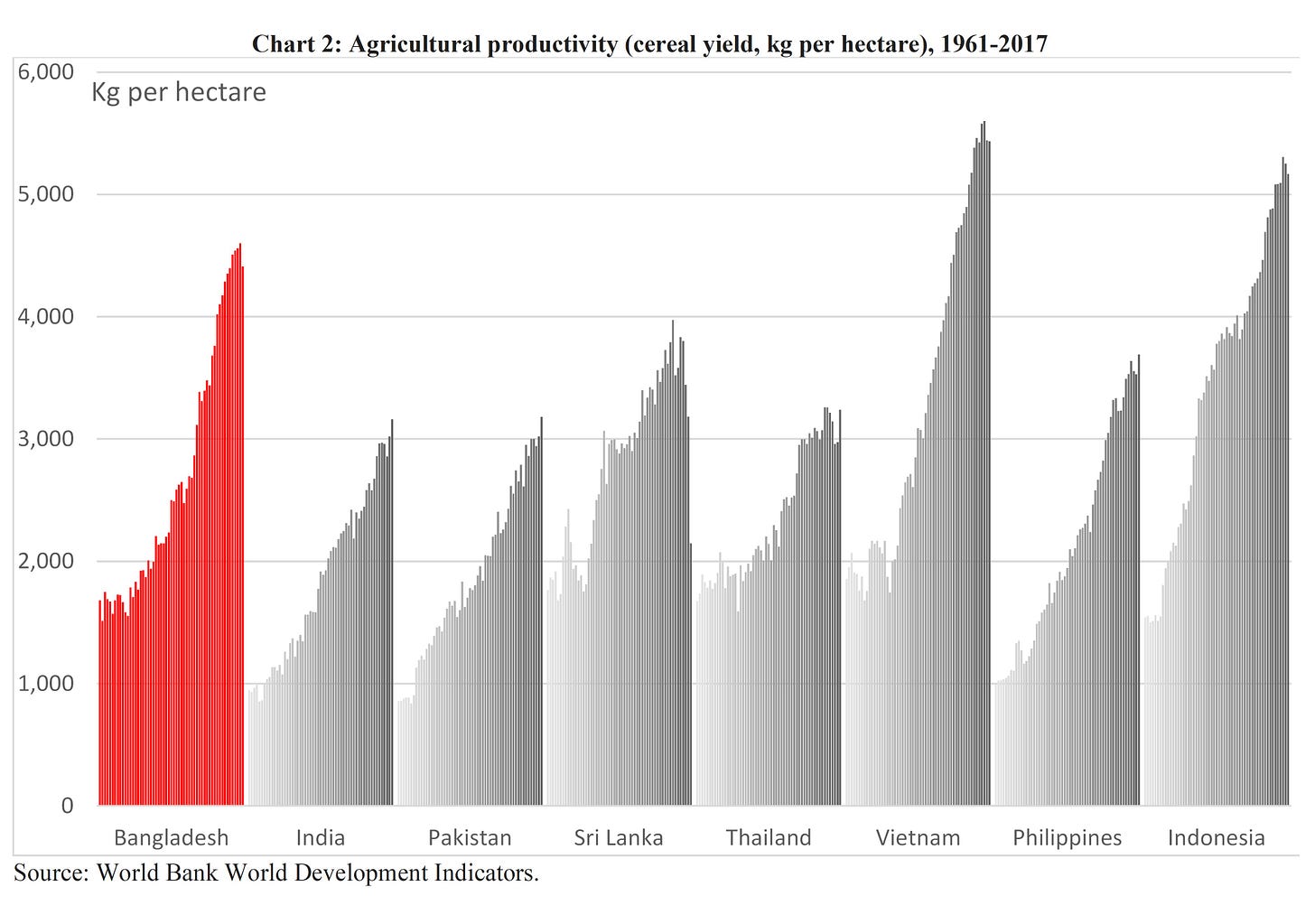

In addition to this structural change, economic development involves productivity improvement within each sectors of the economy. Let’s start with agriculture. Unsurprisingly for a densely populated delta, many more people are crammed into farms in Bangladesh than elsewhere, making the average Bangladeshi farmer less productive than their peers in neighbouring countries. But the average Bangladeshi farm has kept pace with (or outpaced) those from the neighbouring countries over the past half century (Chart 2) by adapting green revolution practices from developed countries to the local circumstances.

It’s a more mixed picture in the industry sector (Chart 3). On the one hand, the average Bangladeshi worker in this sector has been more productive than their Pakistani or Vietnamese peers. On the other hand, they have fallen behind those from elsewhere in the region.

Economic Complexity Index is a measure of how sophisticated a country’s economy is in terms of goods and services produced. More sophisticated countries are ranked higher. Bangladesh has fallen behind our Asian neighbours over the past quarter century (Chart 4).

The garments sector has undoubtedly played a positive role in Bangladesh’s development process. But there is a clear need to diversify the country’s production. Unfortunately, such diversification may be more difficult than commonly perceived. Bangladesh still has a reserve army of millions of rural poor, and women’s share of total employment is still lower than Vietnam or Thailand. As a result, left to market forces, there is little incentive for industrialists to venture out to more risky enterprises.

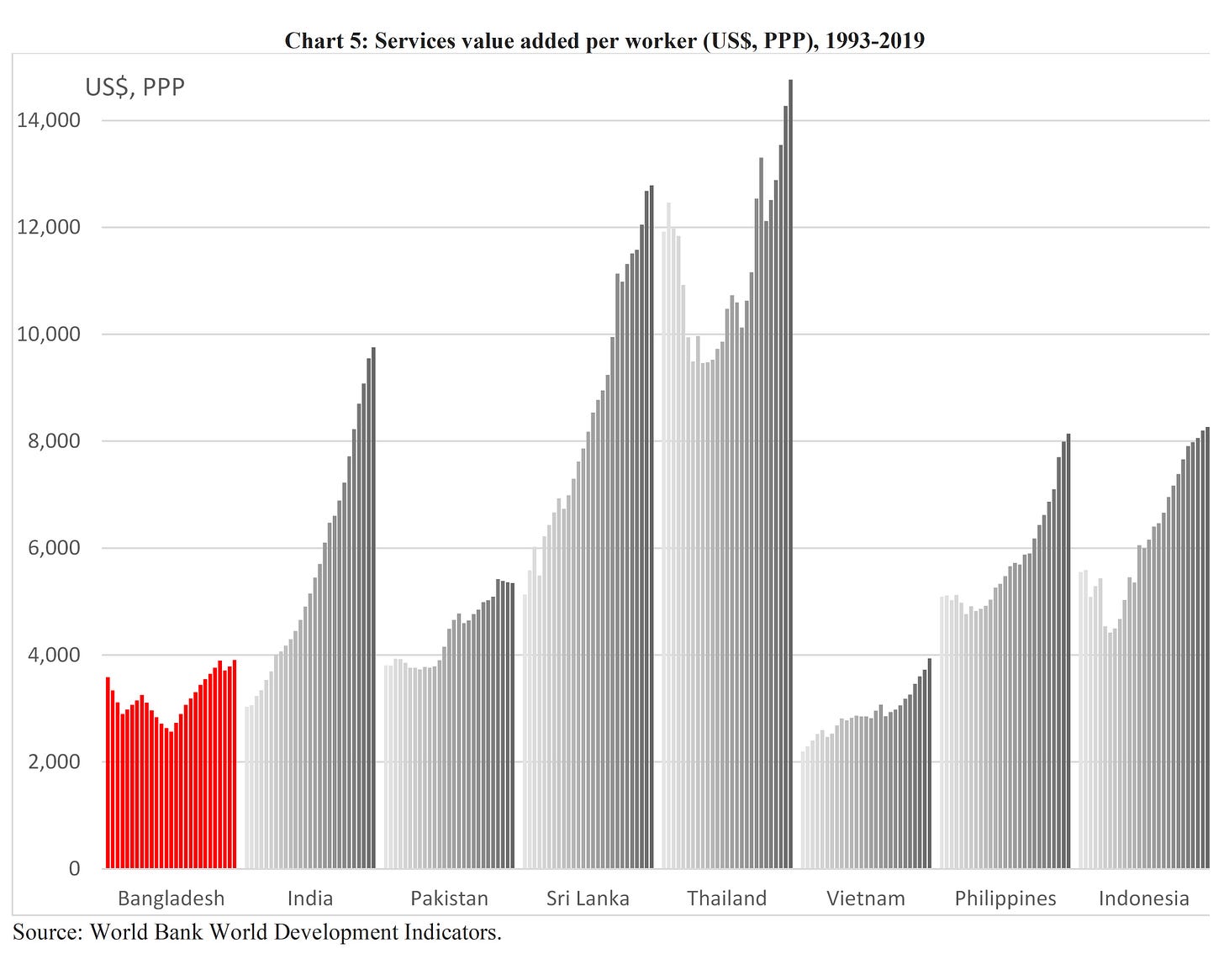

Meanwhile, productivity picture is even more dire in the services sector, which accounts for the bulk of the economy. Services are economic activities such as retail and wholesale trade, transport and communication, finances, health and education, and other such transactions. How people have availed services have changed markedly over the decades. People have long stopped bullock carts as means of transportation, for example. Consumer products that were not available in Dhaka a few decades ago are now available even in rural grocery stores. And smart phones are allowing for all sorts of economic opportunities unimaginable even a decade ago. That is, productivity within services sector have grown over the decades as well. But when compared with the neighbours, Bangladesh’s service sector appears to be woefully unproductive (Chart 5).

Bureaucracy, corruption and nepotism, lack of competent and qualified managers, political interference in dispute settlement, inadequate infrastructure — one can think of many reasons why our service sector remains so unproductive. Sadly, these same reasons also applied five decades ago.

Countries that are open to foreign trade and investment tend to create more jobs, and their workers tend to be more productive. On both counts, Bangladesh is behind Southeast Asian neighbours.

Consider exports. Poor countries typically tend to export agricultural commodities. Starting with Japan in the early 20th century, followed by Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong in the decades after World War II, to China in the past few decades, export-driven industrialisation has brought prosperity to billions. In each of these cases, exported products changed over time, starting with readymade garments, then moving on to toys and light electricals, followed by complex electronics and heavy machinery, eventually to hi-tec products.

Bangladesh have started down the path of exports-led industrialisation in the past three decades (Chart 6). In the late 1980s, jute products amounted to nearly a third of the country’s exports, and other agricultural produces formed another quarter. By 2020, agricultural produces contributed to only 5% of total exports. This industrialisation, however, remains practically solely dependent on readymade garments, which accounted for nearly three-quarters of total exports in 2020.

Exporters operate in a highly competitive global economy. A country that exports a relatively large share of goods and services that it produces is likely to create more jobs in the formal economy, and its workers are likely to become more productive over time compared with a country that doesn’t export much. And Bangladesh still doesn’t export much (Chart 7).

The discerning reader would have noticed that Vietnam exports more than produces. How can that be?

This reflects the fact that Vietnam imports a lot of goods that are than reprocessed into exports. Indeed, this is exactly how the garments industry in Bangladesh operates. By importing the intermediate goods for assembly and re-export, local producers tap into the global supply chain. This, in turn, allows local businesses to adopt better technologies and management practices. Further, imports create competition for domestic firms, pushing them to become more efficient over time. All of that lead to more jobs and more productive workers.

While Bangladesh has a higher import penetration than some of our neighbours, it still remains relatively closed to imports (Chart 8).

Another source of high productivity jobs is foreign direct investment, particularly in the manufacturing sector. When foreign companies set up factories in a poorer country, not only do they hire local workers, over time, many of these workers eventually go on to create their own businesses, generating more jobs and income. Bangladesh, however, does not receive much foreign direct investment compared with the neighbours (Chart 9).

The early years of Bangladesh’s economic policy was dominated by an intellectual paradigm that shunned exposure to foreign trade and investment. While the statist, socialist ideology was abandoned long ago, in practice, Bangladesh still remains a relatively closed economy.

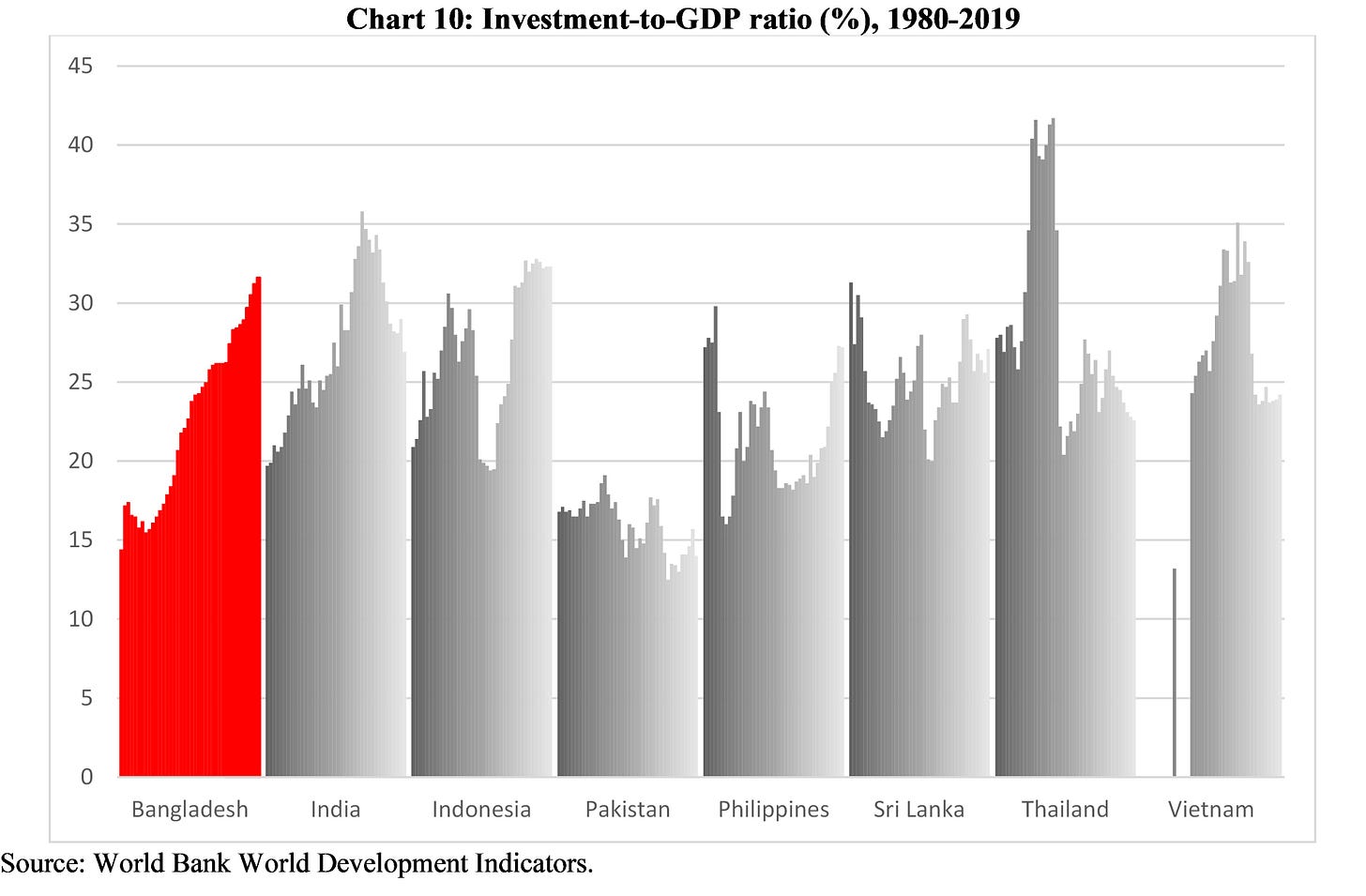

Unfulfilled potential is one way Bangladesh could be described. And this description appears even more apt when the country’s investment records are considered. Over the past quarter century, investment-to-GDP ratio in Bangladesh has risen steadily, to be relatively high compared with the neighbours prior to the pandemic (Chart 10).

To put simply, investment is deferred consumption. When a family puts some money into savings account, buys some assets, sets up a business, or spends on education, the family is investing. Instead of spending that money in consuming goods and services today, the money is put to some use such that the family will have more income, and thus more consumption, tomorrow. Of course, a family only puts aside money for tomorrow only if it believes that tomorrow will be a better day.

Similarly, the higher the share of investment –in new machinery and factory, or infrastructure such as roads and bridges or electricity grid – in the economy, all else equal, the faster the economy is expected to grow. When a country has a low investment-to-GDP ratio, such as Pakistan for example, it implies that its private sector is not confident about future, and its government is preoccupied with the troubles of today. It is reassuring that at least from the macroeconomic data it would appear that Bangladeshis have been hopeful about the future.

When it comes to finances, however, hope and confidence can all too often turn into frenzy and bubble. Similarly, history is full of seemingly productive public investment turning into white elephants of inefficiency and waste. This is why sharp rises in investment-to-GDP ratio can be a cause for concern –such rises are often followed by sudden, painful reversals (such as Indonesia and Thailand in 1997). Fortunately, investment-GDP ratio had been rising gradually, not suddenly, in Bangladesh.

Let’s pause here to reflect. Over the past quarter century, both the private sector and the government has been investing steadily, but foreign-direct-investment has been meagre, and the country hasn’t diversified out of garments.

What’s going on here?

There are two complementary answers. First, Bangladesh needs to maintain relatively high level of investment for years, decades, to come. Second, merely investment is not enough to fulfill the country’s potential.

Consider electricity. Electricity consumption per person had grown 30-folds between 1971 and 2014, and yet the average Bangladeshi was not consuming much electricity compared with the neighbours (Chart 11). That means, a Bangladeshi family still can’t have the amenities that an average Indonesian family can enjoy. And an average Bangladeshi entrepreneur can’t risk ventures that their Vietnamese peers can.

Clearly Bangladesh needs to continue to invest on power plants and electricity grids. But that itself won’t be enough if it takes four times as many days for a firm to get electricity in Bangladesh than Vietnam (Chart 12).

Or let’s consider ports. Liner Shipping Connectivity Index is a measure of how connected a country’s ports are with global trade, based on the number of ports and their capacities, as well as vessels, their size, and the shipping companies and liners. Others in the region have become more connected with the world in recent years, but Bangladesh hasn’t (Chart 13).

Of course, Bangladesh needs to invest more on ports. And yet, that’s not enough. Logistics Performance Index measures a country’s ability to trade. Countries are rated on a scale of a maximum of five. In 2018, Bangladesh’s score was 2.6 against Vietnam’s 3.3.

Let’s consider a couple of other measures. In 2019, it took 274 days on average for a firm to build a warehouse in Bangladesh. In Vietnam, it took 166 days. In the same year, it took the average firm 400 days to settle a contract. In Bangladesh, it took 1442 days.

In 2019, according to the World Bank, Vietnam was the 70th best country to do business in, Bangladesh was 168th.

Bangladeshis are optimistic about the future, and deserve a more enabling environment.

These charts were first published in the Dhaka Tribune.