With the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, economic activities have been severely affected around the world as lockdowns, quarantines, social distancing and other health measures were introduced. The pandemic itself, combined with the public health measures, created an unprecedented economic shock.

Bangladesh has not been immune. But relying on the official GDP figures to gauge the strength of the recovery is unsatisfactory because the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics publishes national accounts only anually.

The series of charts presented here anlyses trends in the following indicators to assess economic conditions: electricity generation; industrial production; exports; imports; credit to private sector; tax revenue; development and non-development expenditure; remittances; workers going overseas; wages; inflation; rice prices; residential rents; interest rates; credit to public sector; foreign reserves; and, stock prices.

Some of these indicators contribute to GDP, while others are correlated with GDP. Then there are measures that, while not directly linked with growth, can still point to the health of the economy or lack thereof. All these indicators are presented as a set of charts on a quarterly basis, and first published in Netra News (see: March 2021; June 2021; and September 2021. Each chart is accompanied by a brief note, and an overall assessment is offered.

The first two instalments, in March and June, confirmed the anecdotal evidence that at least the urban and formal sectors of the economy ground to a halt in 2020, and were yet to show any signs of durable recovery in early 2021. Further, these indicators contradicted the official GDP growth estimates of 5.2% in 2019-20 and 6.1% in 2020-21 (In Bangladesh, financial years are from July 1st to June 31st)

In August, the BBS revised down the official GDP growth figures for both financial years. Chart A shows that the economic growth in 2019-20 was the slowest since the late 1980s. This sharp economic slowdown is consistent with the indicators considered in this series.

The picture for 2020-21, however, is more mixed. According to the revised national accounts, at least a partial economic recovery did take place in that year. Indeed, the indicators considered in our series also point to a recovery, albeit patchy and uneven across different sectors, in the summer of 2021. However, neither the partial indicators nor the BBS GDP figures fully take into account the economic impact of the delta variant. The December update of this series should shed more light on this.

There is one major caveat: the indicators only represent the urban, formal economy, and not the rural, agricultural, and the informal sectors. For all the development of the past 50 years, Bangladesh is still a poor country with a major rural economy as well as a large informal sector. While it is hard to see the informal sector thriving when the formal economy is sluggish, the lack of any explicit indicator of the agriculture sector presents an important shortcoming of the analysis presented.

Overall Assessment

Bangladesh economy, already slowing before the COVID-19 recession, was recovering in the summer of 2021, albeit in an uneven manner. Production and external sector indicators recorded the strongest rebound. In contrast, private investment and government expenditure were yet to recover. The early signs point to a further economic slowdown because of the delta variant outbreak, but the full extent of the damage is yet to show up in data. Policies remain supportive of growth. Stock market appears to be optimistic.

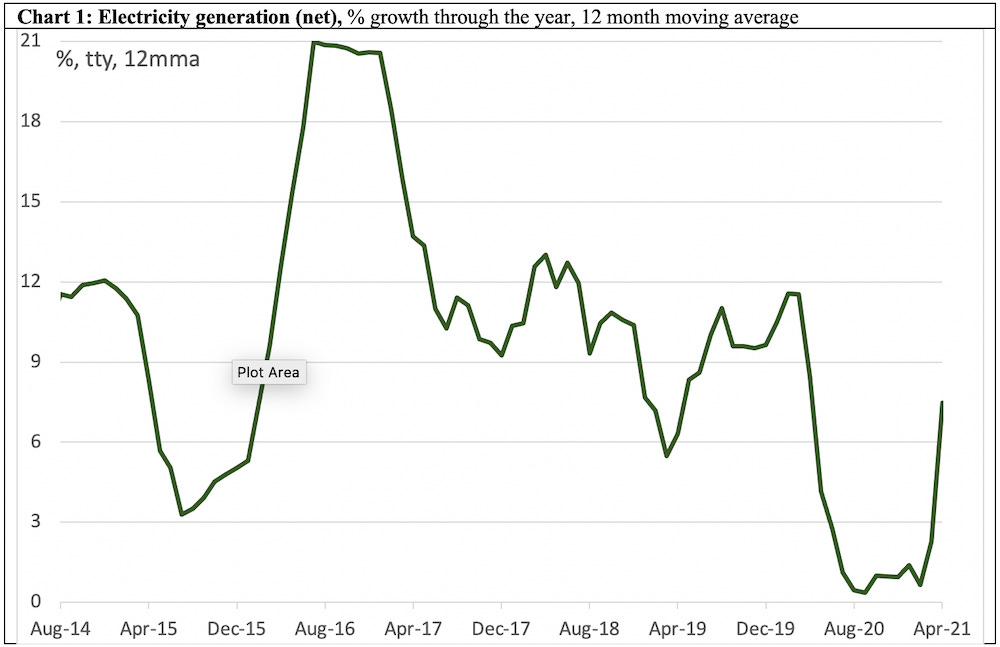

Chart 1: Electricity Generation

Growth in electricity generation is an oft-used correlate of economic activities. Of course, at any point in time this indicator can grow at a different pace than the overall GDP, for example it will grow faster when new electricity capacity comes on line. Prior to Covid-19, electricity generation was growing by 9-11% a year. After stagnating for nearly a year, it grew by by 7.5% in the year to April 2021, pointing to an economic recovery.

Chart 2: Industrial production

Growth in industrial production directly contributes to economic growth. Industrial production in medium and large manufacturing (which covers the readymade garments sector) was already slowing well before the pandemic, with growth in the series declining from a yearly pace of over 15% in the year to the mid-2019 to less than 9% before the pandemic. After nearly a year of stagnation, it had started recovering, growing by 7.3% in the year to April 2021.

Chart 3: Exports

Exports are, of course, a component of GDP. Like industrial production, exports growth started slowing well before the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, exports tanked last year during the height of the global lockdown last year. By December 2020, exports stopped declining on a year-ended basis. Exports were making a healthy recovery in the summer of 2021.

Chart 4: Imports

Mechanically, imports detract from GDP growth — though imported goods and services are either consumed or used for production, and thus indirectly contribute to economic growth. Too fast a growth in imports means the economy is on an unsustainable trajectory. But if import growth is too sluggish then it implies weakness in domestic consumption and investment. Imports were already slowing sharply in the second half of 2019, consistent with the pre-Covid economic weakness in other indicators. Imports also staged a healthy recovery in the summer.

Chart 5 Credit to private sector

Credit to the private sector is a leading indicator of investment by firms and businesses. While too fast a pace of growth in this indicator might signify unsustainable exuberance in the corporate sector, a sustained slowdown signifies a poor investment outcome. Credit to the private sector started slowing in early 2018, with no clear sign of bottoming out as of July 2021.

Chart 6: Tax revenue

Governments typically tax household consumption (including that of imported goods) and household and corporate incomes, all of which contribute to economic growth. Tax revenue growth slowed in the second half of 2019, and then collapsed during the lockdown. Tax revenue recovered strongly in the summer, growing by 19% in the year to July 2021. Strong growth in tax revenue is consistent with the recovery seen in some of the other indicators.

Charts 7 and 8: Development and non-development expenditure

Both development expenditure and non-development expenditure contribute to economic growth. Both collapsed during the lockdown, and neither appeared to have recovered as of May 2021.

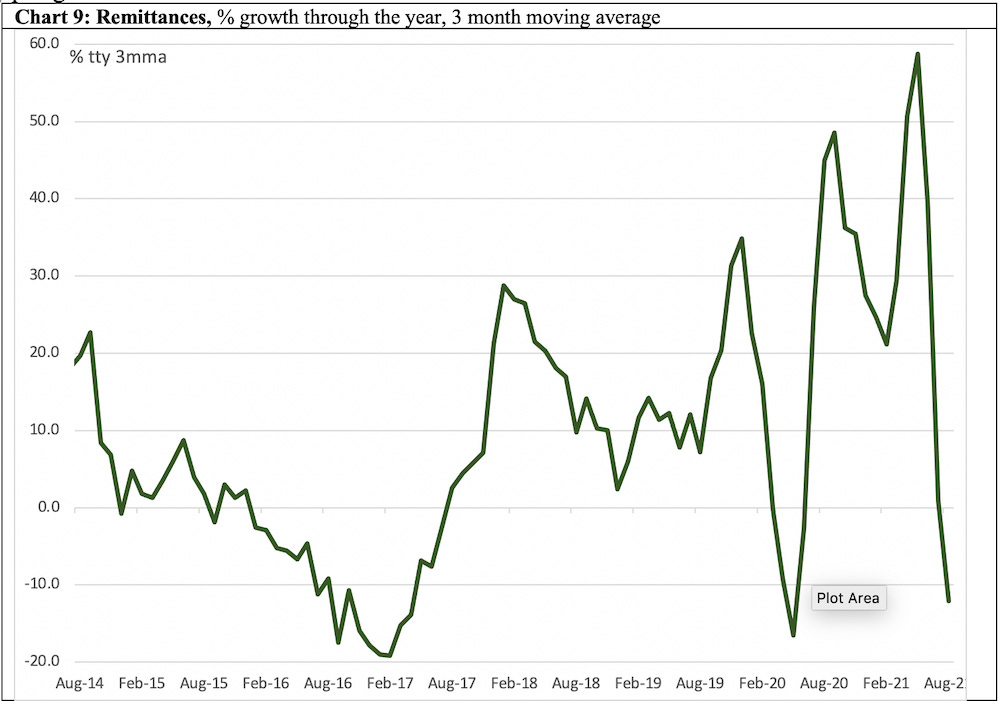

Charts 9 and 10: Remittances and Overseas Workers

While not directly measured in GDP figures, remittances from overseas workers are an important driver of economic growth in Bangladesh. Remittances initially collapsed as the pandemic hit, but then rebounded strongly in the second half of the year. It is important to note that this is the formal measure of remittance. The parallel, informal channel of remittance (the so-called hundi system) almost certainly ground to a halt with travel bans around the world, leaving the formal channel as the only source of remittance. The onset of the delta variant outbreak resulted in renewed decline in remittances in the year to August 2021. Number of workers going overseas ground to a halt in mid-2020, and the delta outbreak has also dampened the recovery in this series that had started in the spring of 2021.

Charts 11 and 12: Wage rate index and inflation

Growth in the wage rate index usually depends on economic growth and inflation. Wages growth slowed sharply in the summer of 2020, but recovered steadily until the onset of the delta outbreak. Inflation has been moderate as of July 2021, except for a food price spike in the autumn of 2020.

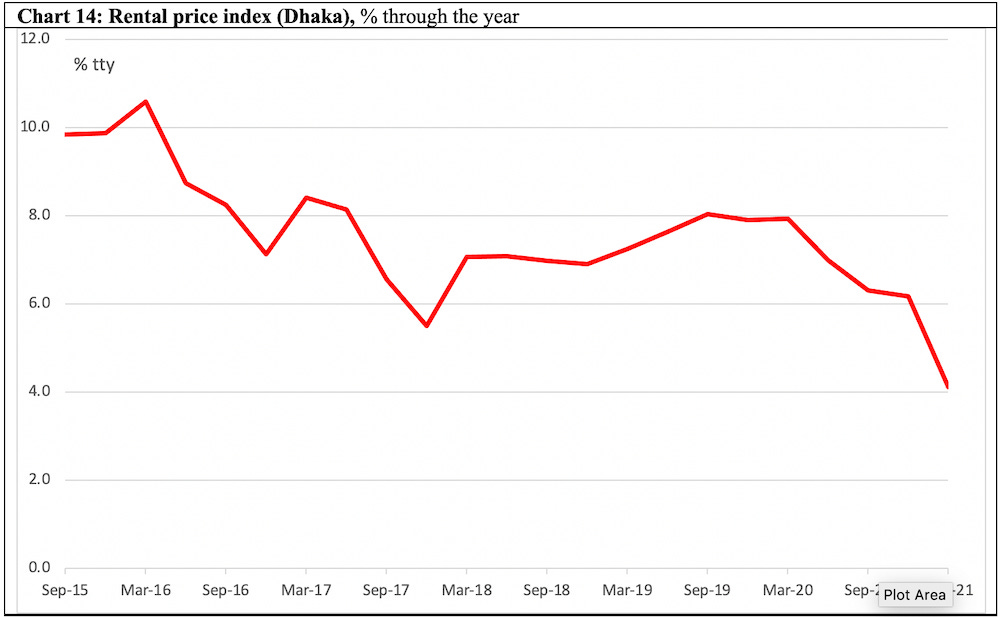

Charts 13 and 14: Price of rice and rental prices in Dhaka

Price of coarse rice in Dhaka corroborates the food price inflation of late 2020, possibly reflecting the effect of the lockdowns on the supply chain. However, the price of rice continued to rise steadily into April 2021, while the official inflation figures had eased. The rental price index in Dhaka recorded a slowdown in mid-2020, consistent with the general economic malaise, and was yet to show any sign of recovery as of the spring of 2021.

Charts 15, 16, 17: Interest rates, credit to public sector and foreign reserves

In addition to the above indicators, government policy settings and actions also affect the economy. Since the beginning of the pandemic, Bangladesh Bank has cut official interest rates, and both deposit and borrowing rates continue to tumble as of August 2021. In theory, this should support economic activities. Public sector borrowing spiked at the onset of the pandemic, but has eased since then. As of June 2021, although Bangladesh Bank’s stock of reserves (expressed in months of imports) has been declining, they continue to be far above what is considered an adequate level (usually said to be three-months), partly reflecting the collapse in imports shown above.

Chart 18: Stock Market

Finally, the stock market is an oft-used, albeit imperfect, forward indicator for an economy. Consistent with many of the indicators above, the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSEX), which fell from mid-2019, and bottomed out in mid-2020, has been rising steadily to August 2021.

All data are from the CEIC Asia Database. Raw data have been smoothed as indicated. The latest available data point in each series is shown in the charts. Next installment is expected to be published in Netra News in December.