Trains to, and from, Pakistan

What a series of academic papers on the Partition teach us about our history

On a warm August night 75 years ago, the sun set on the British Raj. In the mottled dawn that followed came into existence two, then three, countries. Would an undivided India had be a more peaceful one? Would the resources that has been spent on fighting each other had instead been invested for better lives of all peoples of the subcontinent? Or would an unpartitioned India be one of a forever conflict among her peoples?

Such “what ifs” are, of course, impossible to answer. It is, however, possible to untangle many different ways partition did affect people's lives.

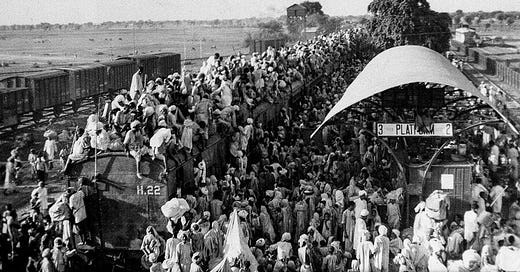

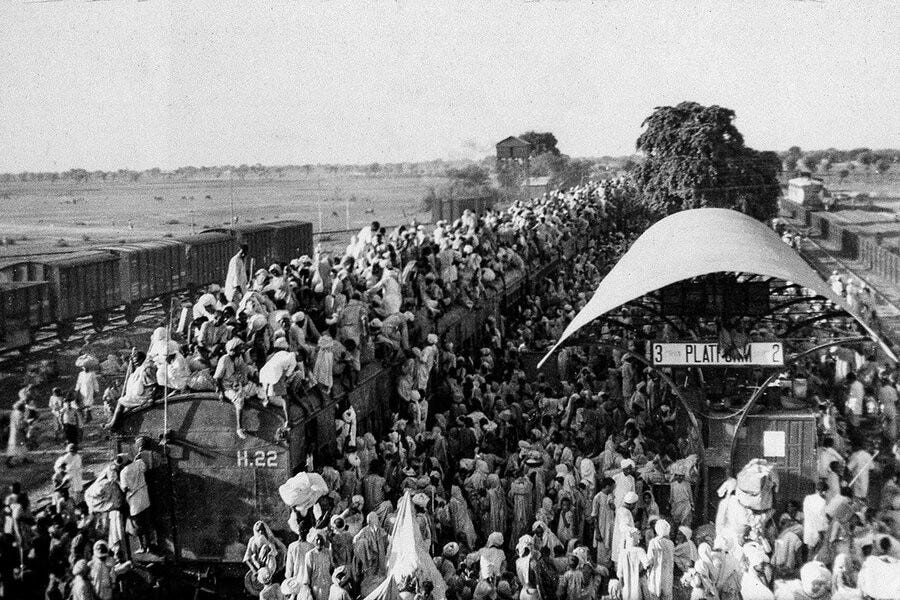

One way economists can shed a new light on historical analysis is through quantification. In a series of fascinating papers, Prashant Bharadwaj -- an economist at the University of California, San Diego -- has been exploring, in a quantitative manner, partition's legacy. His starting point is the massive population displacement -- one of the largest in human history, and the subject of the Khushwant Singh novel whence the title of this piece is taken -- that occurred in the wake of partition.

In a 2008 paper with Asim Khwaja (Harvard) and Atif Mian (then at Chicago, now Princeton), Bharadwaj compared district level data from 1931 and 1951 censuses of British India and the two successor states to quantify the massive cross-border population flows caused by partition.

According to the 1951 census of the two countries, there were 14.5 million people in India and Pakistan in 1951 who moved from the other side of the border. Around 7.3 million Hindus and Sikhs moved to India, while 6.5 million Muslims moved to current Pakistan, and 0.7 million Muslims moved to Bangladesh.

Against the number of “inflows” of partition refugees, the authors estimate potential “refugee outflows” and “missing people.” First, they estimate a counterfactual minority population at the district level that assumes the pre-1931 population trends had continued to 1951. The difference between the actual minority population and this counterfactual yields a potential outflow of 18 million refugees fleeing their home in the wake of partition.

Over 9½ million Muslims are estimated to have left India, nearly 5½ million Hindus and Sikhs fled current Pakistan, and nearly 3 million Hindus might have emigrated out of Bangladesh.

The difference between the “inflow” of refugees and the estimated “outflow” is the 3½ million “missing” people who might have left their home but never arrived on the other side of the border -- a possible upper bound of the lives lost during the 1940s riots.

The authors estimate that around 2¼ million missing people were Muslims -- 1¼ million in the west, the rest in the east. A million Hindus and Sikhs were estimated to be missing in the west, and ¼ million Hindus were missing in the east.

The relatively small number of people emigrating into Bangladesh, juxtaposed against the relatively large number of people fleeing the country, possibly explains why the public memory of partition differs so starkly on the two sides of the Radcliffe Line.

The authors further explored the determinants of outflows and inflows of refugees at the district level. They found that the further from the border a district was, the larger both the inflows and outflows. They also found that districts that had a relatively higher share of minorities to begin with saw a greater exodus, and the districts that lost more people also received greater numbers of refugees. Finally, urban districts received more refugees.

Interestingly, the statistical relationship between these factors and refugee flows were much weaker in the east, suggesting partition played out differently in Bengal than elsewhere.

In a 2015 follow-up, the trio explored the effects of the refugee flows on population characteristics at the district level. For example, partition migrants were typically more educated than those who did not move across the border. This means, outflows would be expected to reduce literacy rate in a district, while inflows would raise it. The authors confirm this was indeed the case in the west. In Pakistan, for example, refugee outflows reduced literacy level by up to 20% in more affected districts compared with districts less affected by partition. Similarly, refugee inflows raise literacy rate by 12%-16% in more affected Indian and Pakistani districts compared with less affected ones.

Interestingly, these flows don't appear to have affected literacy levels in Bangladesh. Put differently, those who had come to Bangladesh around partition were not significantly more literate than their hosts. This may well be another reason why partition does not loom large over our public consciousness.

Partition didn't appear to affect gender compositions in Bangladesh. On the western border, however, there was a gender dimension to partition migration. Indian districts with a large outflow saw a decline in the percentage share of males in total population. Interestingly, the Pakistani districts with larger refugee inflows also saw a decline in the male share of total population. This is because Muslim communities in the north and western parts of the subcontinent seemed to have relatively more men compared with their neighbours.

As with many political upheavals, partition had a very gendered effect on people's lives.

In a more recent paper with France Lu and Sameem Siddiqui (both UCSD), Bharadwaj compared marriage outcomes for women who were adolescent and displaced during partition with those who were older and displaced and those who were never displaced.

The 2021 paper focussed on Pakistani Punjab, and found that adolescent women whose family moved there during partition married earlier, were more likely to marry before 18, and more likely to be married during the years of displacement (1947-49). Further, these women were less likely to continue their education, and had more children over their lifetime.

Bharadwaj's other research points to partition's broader, longer-term economic consequences. For example, before partition, jute cultivation was relatively rare in India. His 2012 paper with James Fenske of Oxford shows that the post-partition take up of jute cultivation in eastern Indian districts can be fully accounted for by the settlement of refugees from East Bengal. The paper shows that not only did the Hindu refugees who settled in eastern Indian districts introduce a new cash crop, but by doing so, they did not depress native wages.

A more recent paper with Rinchan Ali Mirza (Namur University, Belgium) explores longer term economic consequences of partition migrants. The authors show that refugees were not settled into districts that had any distinct potential for agricultural development. However, Indian districts that received more refugees in the 1940s were also the ones where the green revolution was more successful in the subsequent decades. The authors hypothesize that the higher literacy among the refugees might have played a role in boosting agricultural productivity, but acknowledge that more work is needed in this space.

Reading these papers, one cannot help but wonder what a similar effort might uncover about Bangladesh's history, not just around partition, but also more recent upheavals. For example, the 1961 and 1981 censuses could be used to disentangle the effects of the Liberation War or the famine of 1974. There is no reason why curious Bangladeshi scholars couldn't contribute to this literature.

First published in the Dhaka Tribune, this is the latest piece commemorating 75th anniversary of Partition. Previously in the series:

The Bharadwaj papers referred to in the piece.

The Big March – Migratory Flows After the Partition of India (with Asim Khwaja and Atif Mian). Economic and Political Weekly, August 2008, Vol 43(35), pp. 39-47

Partition, Migration and Jute Cultivation in India (with James Fenske). Journal of Development Studies, April 2012, Vol 48(8), pp. 1084-1107

The Partition of India – Demographic Consequences (with Asim Khwaja and Atif Mian). International Migration, August 2015, Vol 53(4), pp. 90-106

Displacement and Development: Long-term Impacts of Population Transfer in India (with Rinchan Ali Mirza) Explorations in Economic History July 2019

Marriage Outcomes of Displaced Women (with Frances Lu and Sameem Siddiqui) Journal of Development Economics, September 2021

Further reading (and listening)

The short history of Bengal’s greatest festival

Shoaib Daniyal, 21 Oct 2015

The Economist’s India reading list

12 August, 2022

Who is Sir Ganga Ram and why his legacy lives on in India and Pakistan?

Sajid Iqbal, 12 August 2022

‘Tears of the Begums’ is an elegant translation of harrowing testimonies following the 1857 revolt

Originally published in 1944 in Urdu as ‘Begumat ke Aansoo’ by Khwaja Hasan Nizami, the book has been translated into English by Rana Safvi.

Raza Mir, 3 Sep 2022

Colonial subjects who refused to acquiesce to the asymmetry of power between the ruler and the ruled paid a heavy price.

Dipankar Das, 9 Oct 2022

Razib Khan’s recommended books on India

12 Nov 2022

Faham Abdus Salam’s videos on Hindustani Mussulman