Plain tales of the Raj

A study of India before and after the Raj

Sir Roger Dowler of Bengal was a terrible, terrible guy who used to spend all his time boozing and doing wicked, wicked things with women, all the while his countrymen were impoverished by rapacious men of avarice who loafed around in the capital.

What? Never heard of Sir Roger? Sure you have, except you know him by his real name -- Siraj-ud-Daulah, the last independent nawab of Bengal.

John Company’s men anglicized Siraj’s name. They also wrote about him being a very bad ruler, from whose misgovernance the people of Bengal had to be delivered by Clive and his men. And that historiography essentially continued with the orientalists of the 19th century all the way to the 20th century Indian historians like Jadunath Sarkar and Ramesh Chandra Majumdar.

Of course, that history is not what any school child in either Bengal learns. What we learn is this:

Okay, maybe not exactly that song. But that Siraj was undone by a palace coup involving his generals, bankers, relatives, and of course, the perfidious Clive and his mates -- is the accepted history in Bangladesh (and elsewhere in South Asia). And both histories have clear political purposes. The Sir Roger version was used to justify British imperialism. And the late Anwar Hossain as Bangla’r Nawab was a nationalist icon.

An alternate reality

This year marks the 275th anniversary of the so called Battle of Plassey. So called because both versions of the history agree that no battle of significance was actually fought at Plassey on June 23, 1757. Had there been actual fighting, sheer numerical superiority probably would have handed the Nawab a victory.

What might have happened if Siraj-ud-Dowlah had won?

His army would almost certainly have burnt Calcutta to the ground. The East India Company would have lost all its privileges in Bengal. But would it have survived in the South? The Madras presidency was a separate entity, and there is no reason why it would have folded if Calcutta was lost. But would the Company have been so weakened that it would have ceased its rivalry with the French? And if the English Company was sufficiently weakened, would the Dutch Company have returned to the game?

By the 1750s, the Mughal Empire was in the process of disintegrating. There were principalities -- Hindus and Muslims, large and small; Bengal, Hyderabad, and Awadh, all Muslim, being the three large ones -- that accorded the Mughal throne de jure allegiance while maintaining de facto independence. These post-Mughal states weren’t always friendly with each other. And then there was the Maratha confederacy, the first Hindu power in many centuries to seek mastery of the entire land between the Himalayas and the ocean.

The European companies operated in this world. In "the famous 200 days," Clive gained control of Bengal and put the English Company way ahead of its French rival (the Dutch had conceded the contest earlier). Had Plassey gone the other way, the French perhaps would have come out ahead.

Or perhaps not.

We know that Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan of Mysore were no anglophiles. Bengal and Mysore probably would have become French allies, but perhaps the English would have formed an alliance with the Marathas. Perhaps in the course of the next few decades, a stand off would have ensued, with two alliances -- French backed Bengal-Mysore entente and the English-allied Marathas -- facing each other across the remnants of the Mughal Empire.

Which way would Hyderabad, Awadh, and various Rajput and Afghan princes have gone?

There is no reason to think that the developments in the subcontinent would have significantly affected the American and French revolutions. But Napoleon’s defeat would almost certainly have weakened the French Company. While this might have meant a Maratha ascendancy across India by the 1810s, a Maratha supremacy would by no means have been a certainty.

By the 1820s, Ranjit Singh would have added his Sikh kingdom to the game. Fearful of the expansionist power to the north beyond Hindu Kush and the Oxus, the Sikh king would likely have sought alliance with some other European power, but who would that power have been?

By the 1840s and the 1850s, India would have become the setting of a great game of intrigue and high politics involving home grown and foreign players. How would the game end? Would there have been one massive war? Or would there have been a cold war? Who would have come out on top in that Great Game?

Would the victor of the Desi Great Game become a global power to challenge the Europeans? Or would it have limped into the 20th century like the Ottomans? Perhaps it would have become prey to foreign interventions and informal colonialism, like the Ming China? Or perhaps there would have been a Desi version of the Meiji Restoration.

Of course, all these possibilities were foreclosed on June 23, 1757.

Leaving an impression

The biggest effect of the British rule on the Indian people was this denial of possibilities, Amartya Sen argued in the pages of the New Republic, convincingly demolishing Niall Ferguson’s pro-Empire narrative. As an aside, Pankaj Mishra’s smackdown of Ferguson in the pages of the London Review of Books is far fiercer, and thus more entertaining. Shashi Tharoor’s writings on the evils of the Raj, on the other hand, are perhaps as one sided in pushing the nationalist case as Ferguson’s is from the imperialist side.

There is seldom agreement among economists about what is happening right now, for example, in the foreign exchange market. It is therefore not surprising that there is no agreement among economic historians about the economic legacy of the Raj.

One way to look at the economic relationship between India and Britain during the late 19th century is to use the prism of "home charges." Indian government (that is, the Indian taxpayers through the British imperial administration) was required to pay the British government the cost of running a cabinet department on India in London, costs of all wars where British Indian army participated (of course, Indians had no say in which wars to participate in), maintenance of British Indian army and other security services, pensions of all British military and civilian officers, and an annual 6% guaranteed return to the shareholders who invested on the Indian railway. Annually, these charges amounted to about 5% of productions in India and incomes of the Indian people.

Another way to look at the economic relationship is through trade balances between India, Britain, and the rest of the world. India ran huge deficit with Britain -- Britain sold manufactured goods and bought agricultural products. India ran huge surplus with the rest of the world, who bought Indian agricultural products but couldn’t sell much to Indians because the market was closed. Britain ran large deficits with the rest of the world, which was paid for by the surplus with India.

One argument is that the trade relationships just reflected comparative advantages of different economies, and there wasn’t anything sinister about it. A stronger argument is that the 5% of the income flowing from India to Britain every year reflected return on investment which benefitted both the British and the Indians -- railway was after all what unified India, and without the British "justice," India would have been a far worse place to live in.

Right on track

Dave Donaldson, an economist at the MIT, has done the seminal work on the economic effects of the railways of the Raj. Without the railways, bullock carts with a travelling speed of 30km a day would have remained the dominant mode of transportation across the subcontinent. Trains had a speed of 600km a day, and could carry goods at a much lower freight cost. The rail network connected distant parts of the subcontinent with each other, and the world. Using vast archival records of district level data -- on prices, output, trade, rainfall -- collected by the Raj, Donaldson explored how the analyzed the economic effects of the expansion of the railway network.

Specifically, theoretical models of trade predict that lowering of transportation costs would allow regions to increase trade, benefitting everyone. Donaldson estimated the effect of India’s railroads on the national trading environment, demonstrating that railroads reduced the cost of trading, reduced interregional price gaps, and increased trade volumes. He found that when the railroad network was extended to the average district, real agricultural income in that district rose by approximately 16%. He also found that railroad line projects that were scheduled to be built but were then cancelled for plausibly idiosyncratic reasons did not increase income.

That is, railways of the Raj did improve people’s lives.

But then again, it’s hard to argue that it was in the Indian taxpayers’ interest to pay for wars in faraway places. Even with the railway, not everything was beneficial -- tracks were laid with no consideration to local factors, keeping only the ease of troops movement in mind, resulting in major ecological problems.

More importantly, what was the opportunity cost of the 5% "drained away" every year? Without the Raj, could that income have been invested into something productive at home? Here the nationalist critique is on thinner ground. It’s difficult to make a convincing argument that these resources would have resulted in homegrown economic growth, and not simply been consumed by a rapacious local elite.

In any case, the British manufacturers needed a sizeable class of consumers in India to buy their products. And the Empire needed a local collaborator class -- they learnt the lesson of alienating powerful locals in 1857. The solution was to encourage cash crops like jute or cotton, which produced a local middle class that could buy the British goods. Eventually, it’s this class that also took on British ideas like democracy and nationalism.

The truth behind the numbers

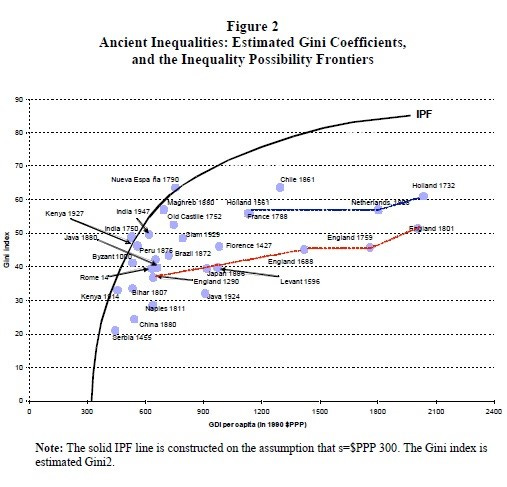

Work by Branko Milanovic, a former World Bank economist and an expert on inequality, can help shed further light on the matter. His innovations in the study of inequality are the inequality possibility frontier and the inequality extraction ratio. The first concept is a measure of maximum possible inequality in a society -- essentially, an economy that is on the inequality possibility frontier is where most people (say "the 99%") are on subsistence, while the rest of the income accrues to the elite (say "the 1%"). The inequality extraction ratio compares the actual inequality in an economy with the maximum possible given its income level.

An economy that is very close to the frontier, and thus has a ratio near 1, is where there isn’t any surplus left in the hands of the non-elite. Not only Milanovic and colleagues theorize about these concepts, they have also calculated them for a number of societies in history, with two entries for India -- in 1750 and 1947, bracketing the Raj. This chart summarizes their finding that is relevant for us.

The chart shows that before the onset of the British rule, in 1750, India had roughly similar per capita income as China in the late 19th century or the Byzantine empire around 1000. But India’s inequality extraction ratio was actually slightly above 1 -- that is, the elite extracted all the surplus and then some, and most Indians lived below subsistence. Fast forward two centuries, and when the British left, per capita income rose by a little bit, and the inequality extraction ratio fell just below 1 -- that is, the average Indian continued to be very poor, and most Indians now were living just above subsistence, with the elite extracting almost all the income produced in the economy. Of course, the elites in 1750 and 1947 were not identical. But it seems that as far as the aam aadmi is concerned, Mughals and the British made little difference.

Of course, there is always a margin of error in these kind of studies. So don’t get too hung up on the exact numbers. Rather, think about what the chart -- if correct -- might mean for the broader debate. Had Clive not won in Plassey, would India have industrialized? None of the other economies close to the frontier in the chart (except one -- see below) went on to industrialize, so why would India be different?

Now, that’s not quite the end of the story.

Firstly, two centuries later, when the British left, India was still a highly exploited place. And yet, India (and Pakistan and Bangladesh) have been developing for over seven decades now, at pretty strong pace at times. So it’s not the case that "exploited now" means "exploited forever."

Question then is, why did independent India and her neighbours develop? The "pro-Raj" argument might be that the British had left India with a set of institutions -- democracy, rule of law, English language, cricket -- that made the difference. But then again, one could argue that modern India’s founders -- Pundit Nehru and colleagues -- deserve the credit for these institutions, and the British contribution might not have been much.

For example, Lakshmi Iyer of the University of Notre Dame compared the economic performances of areas that were directly ruled by the Raj with the “native states” that remained under the indigenous princes. She finds that the British annexed the more fertile, economically more attractive parts of the subcontinent, but then didn’t invest as much on the areas under their rule as was done by the native princes. The effects are still visible in economic outcomes and living standards.

So, it seems to me that the interesting question is not about how similar India was before and after the Raj, but how different it was despite the apparent similarities.

First published in the Dhaka Tribune as part of a series marking the 75th anniversary of the end of the Raj. Photo credit: DT.

Previous articles in the series:

Papers

Donaldson, Dave. 2018. "Railroads of the Raj: Estimating the Impact of Transportation Infrastructure." American Economic Review, 108 (4-5): 899-934.

How large are the benefits of transportation infrastructure projects, and what explains these benefits? This paper uses archival data from colonial India to investigate the impact of India's vast railroad network. Guided by four results from a general equilibrium trade model, I find that railroads: (1) decreased trade costs and interregional price gaps; (2) increased interregional and international trade; (3) increased real income levels; and (4) that a sufficient statistic for the effect of railroads on welfare in the model accounts well for the observed reduced-form impact of railroads on real income in the data.

Milanovic, Branko. 2013. The Inequality Possibility Frontier : Extensions and New Applications. Policy Research Working Paper;No. 6449. World Bank, Washington, DC.

This paper extends the Inequality Possibility Frontier approach in two methodological directions. It allows the social minimum to increase with the average income of a society, and it derives all the Inequality Possibility Frontier statistics for two other inequality measures besides the Gini. Finally, it applies the framework to contemporary data, showing that the inequality extraction ratio can be used in the empirical analysis of post-1960 civil conflict around the world. The duration of conflict and the casualty rate are positively associated with the inequality extraction ratio, that is, with the extent to which elite pushes the actual inequality closer to its maximum level. Inequality, albeit slightly reformulated, is thus shown to play a role in explaining civil conflict.

Lakshmi Iyer; Direct versus Indirect Colonial Rule in India: Long-Term Consequences. The Review of Economics and Statistics 2010; 92 (4): 693–713.

This paper compares economic outcomes across areas in India that were under direct British colonial rule with areas that were under indirect colonial rule. Controlling for selective annexation using a specific policy rule, I find that areas that experienced direct rule have significantly lower levels of access to schools, health centers, and roads in the postcolonial period. I find evidence that the quality of governance in the colonial period has a significant and persistent effect on postcolonial outcomes.

Other reading

Victorian England’s foremost rotter would have made a great journalist

24 December 2016.

“Child of Empire” documents one of the largest forced migrations in history from the perspective of two children

7 February 2022.

Excerpts from a 19th century account

3 May 2022

17 May 2022

Internecine Mughal wars of succession

June 2022

Chris Wellisz profiles Harvard’s Melissa Dell, who pioneers new ways of unmasking legacies of the past

Good read.