Nirad C Chaudhuri and Jatin Sarker were both born in Hindu families in the Mymensingh district of eastern Bengal, now Bangladesh. Chaudhuri, about four decades older than Sarkar, wrote his autobiography before India held its first election, and ceased to be an unknown Indian. Sarker also wrote his life story. Unlike Chaudhuri, Sarker’s was in Bangla, published in Bangladesh, never translated in English, and not widely available. He remains unknown. Which is a pity, because Sarker is a far, far better guide than Chaudhuri when it comes to the land of their birth.

Sarker, of course, stopped being an Indian on 14 August 1947, when Mymensingh became part of East Pakistan — the rural slum of Jinnah’s moth-nibbled two-winged land of the pure. His family didn’t move to India. They were not atypical. Many Hindu families remained in East Pakistan. Perhaps it was the presence of Gandhi. Perhaps it was the fantastical belief that Subhas Chandra Bose would return in 1957 — a century after the Great Uprising, two centuries after the Battle of Plassey — to reunite Mother Bengal.

There were no trains full of dead bodies to and from Calcutta. Not that there was no Hindu exodus from East Pakistan. Far from it. In 1941, 28 per cent of the people of the districts that became East Pakistan were Hindus. Two decades later, the share had dropped to 18.5 per cent. There were emigrations in dribs and drabs, with major outflows during the communal violence of 1946, 1950, and 1964.

There were riots in India, too. West Bengal was a peripheral state in the Indian Federation. Those Hindus who moved from East Pakistan to India — mainly but not wholly to Calcutta — became part of that troublesome city’s doomed teeming multitudes. No one really cared much for them in Delhi or Bombay, where power and wealth resided.

What of those who stayed back?

Sarker describes the lives of middle class bhadralok Hindus of mofussil East Pakistan in Pakistan-er Janma Mrittu Darshan (‘Witnessing the Life and Death of Pakistan’). While he stopped being an Indian on 14 August 1947, he didn’t become a Pakistani. That country became an Islamic Republic. Hindus were not equal citizens there. They were dhimmis, under the ‘sacred protection’ of the majority.

Sarker could never be a Pakistani, but his Bengali Muslim neighbours did not quite feel at home in Pakistan either. In 1971, when East Pakistan died and Bangladesh was born, Sarker thought he would become an equal citizen of a free country. A country that was created with the sacrifice of Hindus and Muslims alike —the image below lists Hindu staff and students of Dhaka University gunned down by the Pakistan army on 25 March 1971.

And on paper he is. Bangladesh never became an Islamic Republic. There is no formal discrimination with respect to religion. Hindus are not formally denied a job, a bank loan, or admission to an educational institution (except madrassahs of course). On paper, Sarker has no reason to write Bangladeshey Pakistan-er bhut darshan (‘Witnessing Pakistan’s Ghost in Bangladesh’), a hypothetical sequel where he might have talked about things that one did not wish for in the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

The exodus of Hindus, for example, which continued after 1971. Bangladesh’s first census in 1974 saw the proportion of Hindu population fall to 13.5%. By 2011, it had further fallen to 8.5 per cent.

How do we know this steady decline in the Hindu share of population is because of exodus, and not differential fertility rate? That’s exactly what M Moinuddin Haider (ICDDR, B), Mizanur Rahman (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), and Nahid Kamal (a consultant) investigated. They found that over half of the slower growth in Hindu population (compared with other Bangladeshis) between 1989 and 2016 was attributable to emigration.1

As Shafiqul Alam, the most astute chronciler-in-English of Bangladesh-outside-Dhaka’s posh-suburbs, put it in a Facebook status:

For a long time Hindus in my part of rural Bangladesh were reluctant to invest in new homes, Samadhis and temples. I have a very good relations with many of these families and I would ask them why their homes were in such a dilapidated conditions. Why didn't they build new homes, refurbish their centuries-old Kali or Radhakrishna or Shitaladevi's temples? There was a general silence over the issue. I pressed, but they did not open up.

Not that they were financially worse off than their Muslim neighbours. In fact many of them have done well by investing in education of their kids and seizing opportunities in the massive expansion of non-farm jobs in the villages. A lot of their children grew up to become government employees, private sector managers, bankers and police constables and officers. So, many of them had money, yet they were reluctant to invest in new homes, expensive memorial Samadhis for their deceased parents or building new temples.

There is no Gujrat moment for the Hindus of Bangladesh. Nothing like the anti-Sikh violence that engulfed India in 1984 had ever happened in Bangladesh. Last time there was violence in that scale was in 1964.

What then continues to drive the Hindus out of Bangladesh? Two factors come to mind: a complex interplay of socioeconomic factors that make the life of a typical Bangladeshi Hindu much more miserable than their neighbours; and this banal, accursed life is interspersed with outbursts of violence which is fostered by an increasingly dysfunctional, authoritarian political landscape where most members of the community are treated as expendable untermensch.

To borrow Hannah Arendt’s words, Bangladeshi Hindus face a banality of misery, a myriad of biases and discrimination at school, university, jobs, banks that bluntly remind them their essential otherness in this delta.

If you don’t know what I refer to, think about the last time you had heard the word malaun in polite company.

Now, the mutual apathy and distrust, if not overt antagonism, between the eastern subcontinent’s two large religious communities (and multiple ethnic communities) is far too complex, and no one is better off with simple tales of eternal harmony. As Annada Shankar Ray noted, the two communities had co-existed in the region for generations, centuries, without really intermingling.

Of course, that complex interplay of historical legacy affects the Hindu-Muslim interpersonal interactions on a daily basis. However, in a fascinating experiment, Pushkar Maitra (Monash University) and colleagues in Kolkata and Dhaka show that it is the minority status, not religious identity itself, that drives people’s behaviour.2

Specifically, they find that minorities in both West Bengal and Bangladesh show more trust towards their fellow minorities, whereas members of the majority community show no such trait. That is, a Muslim in West Bengal trusts a fellow Muslim more than a Hindu, but a Bangladeshi Muslim is indifferent between the communities. The authors further find that in case of West Bengali Muslims, the driver of differential behaviour is favouring fellow community members, whereas for the Bangladeshi Hindus, distrust of the Muslims is a bigger factor.

The historical legacy of the divergent paths taken by the two communities in the 18th and 19th century continue to have economic consequences even in today’s Bangladesh. Salma Ahmed (Deakin University) finds that even in the decade to 2009, Hindu male workers earnt more than their Muslim colleagues across the wage distribution because they were better educated on average.3 But she also found that even among the high income earners, Hindu men faced discrimination and earnt less than might have been expected from their qualification.

There is, of course, no law supporting discrimanation against Hindus. There is, however, a law that makes the community particularly vulnerable — The Enemy Property Act 1965 and its Bangladeshi successors.

The Act allows the state to seize properties of those who leave the country. In practice, this has been used over the past four decades to grab Hindu properties. Typically, local big-wigs grab some prime land, and then use death or emigration of one of the family members as an excuse to enlist the entire property. If emigration is not voluntary, coercion or intimidation is commonplace.

According to Abul Barakat (Dhaka University), as of 2000, over two-fifths of Hindu households had been affected by the Act, leading to a loss of over half of their land (over 5 per cent of total land area of Bangladesh).4 This transfer of land, however, benefitted less that 0.4 per cent of Bangladeshis. This had been no land reform by the state on behalf of the poor and downtrodden. The beneficiaries were those with the might that comes from political connections.

What were the political affiliations of the offenders? According to Barakat, over 44 per cent of the land grabbers were connected with the Awami League, more than the combined total of BNP, Jatiya Party and Jamaat-e-Islami linked offenders.

And thus we come to the dysfunctional polity that curses the life of Bangladeshi Hindu.

Yes, there has been no Gujrat moment in Bangladesh. But there has been violence. In November 1990, during one of LK Advani’s marches to the still standing Babri Mosque, violence broke out against the Hindu community in Dhaka and Chittagong. Two years later, when the centuries-old mosque was razed to ground, temples were desecrated across Bangladesh. On both occassions, the state machinery moved quickly to restore order.

Khaleda Zia was the prime minister when the mosque in Ayodhya was demolished, and seems to have remembered the experience very well. The Gujrat rampage happened during her second stint in power. Her government ensured that there was no reprisals against the Hindu community in Bangladesh. She was also acutely aware of the communal violence that marred her return to power in 2001.

Of 300 seats in Bangladesh’s parliament, Hindus were a non-trivial minority in about 70. In a tight election such as those between 1991 and 2001, their votes could make a huge difference. Not allowing them to vote was one way of reducing their influence. That is precisely what happened in 2001. In that election, Awami League received 40% of the votes, against BNP’s 41%. Before the 2001 election, there was widespread violence and intimidation against Hindu voters who had supported AL in the previous elections. And those who did vote for AL became the victim of targetted communal violence after the election.

Bangladesh’s stressed and stretched electoral democracy failed to safeguard the Hindu community.

The story, of course, does not end there.

Two decades later, images and stories of the victims of 2001 resurfaced in a toxic cocktail of misinformation and propaganda against Mamata Banerjee in the 2021 West Bengal election. Majoritarian democracy is not sufficient to safeguard citizens’ rights, this much is self-evident when one looks across the Radcliffe Line.

Of course, discarding democracy is guaranteed to extinguish citizens’ rights, this much is also self-evident when one just thinks of Bangladesh of the past decade.

Awami League was elected in a landslide on the promise of din bodol, which almost immediately resulted in the good old ways of giving plum jobs to ill-qualified party hacks. Trouble is never far away when that kind of thing happens. The infamous case of Porimal Jayadhar, teacher in a top girls’ school who raped his students, is already a decade old. It’s not that only the Hindu partisan appointees have been guilty of terrible crimes of omissions and commissions. There are plenty of Muslim hacks too. But the fear is that the sins of a handful of Hindus might lead to trouble for the whole community when political landscape change.

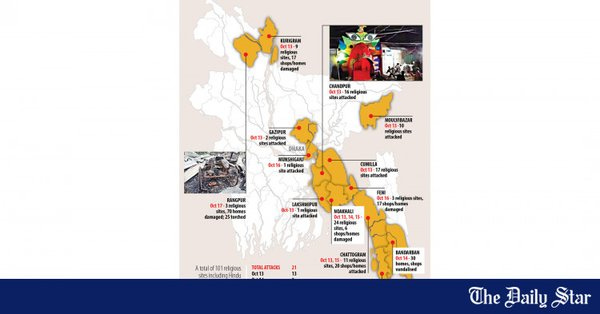

Political change in Bangladesh may or may not be in near or distant future. In the Bangladesh under the supposedly secular, inclusive government of Hasina Wajed, however, there has been repeated communal violence, with active connivance of her partymen, in Ramu, Nasirnagar, Shalla, Muradnagar, and last week, across the country.

The first paragraphs of this piece was taken from a piece I wrote over a decade ago for the progressive Indian blog Kafila, cross-posted in the now-defunct Unheard Voices blog. Re-reading the old post, I am struck at the sense of innocence, naivete, and hope. Shabnam Nadiya, a dear friend, described her own fifteen year old piece in a Facebook status that might apply to me too:

Back when my understanding of privilege, prejudice, hatred oozed with naïveté, the privilege of being sheltered. But above all, back when my understanding of our society was still permeated with hope.

A different facebook post by another friend asks pointedly5:

সেই বাংলাদেশ শুধু চেয়ে বসে থাকলে হবে? যেই বাংলাদেশ চেয়েছিলেন তার জন্য কাজ করতে হবে না?

(Don’t you need to work for the Bangladesh that you wanted? Is merely wanting that Bangladesh enough?)

So, what kind of Bangladesh do we want, and what can we do about it? We might want a Bangladesh where the M-word is as acceptable in polite company as the N-word is in the west. But that kind of social transformation will take a long while. A more achievable, practical work programme for a liberal Bangladesh for here-and-now would involve politics, for a liberal society is not possible in an illiberal polity.

Unfortunately, there isn’t the slightest sense of irony in the status above. The poster appears to be completely oblivious to the fact that one cannot possibly expect communal harmony and tolerance under an authoritarian regime.

Three quarters of a century ago to this very week, this delta was red with communal bloodletting that couldn’t have been stopped by the British Raj in its last days, until a frail old man came with a message of peace.

There is, of course, no Mahatma in Bangladesh. But nor is one needed. It would suffice for the state machinery to do what it did in 1990, 1992, or 2002.

But the reality is that in the past decade, the Bangladeshi state has become very good at stamping out dissent, but given the rot, it has become very bad at statehood and the type of resolute action that would have thwarted these attacks.

Until and unless there is an honest acknowledgment that the state is broken and needs to be rebuilt, Bangladesh will remain an accursed place, for all her citizens.

Photo credit: Udayan Chattopadhyay. I am indebted to the research of two colleagues whom I have not named because of their safety.

Haider MM, Rahman M, and Kamal N, 2019, Hindu Population Growth in Bangladesh: a demographic puzzle, Journal of Religion and Demography.

Gupta G, Mahmud M, Maitra P, Mitra S, and Neelim A, 2018, Religion, minority status, and trust: Evidence from a field experiment, Journal of Economic Behaviour & Organisation.

Barakat A, 2000, Inquiry into Causes and Consequences of Deprivation of Hindu Minorities in Bangladesh through the Vested Property Act.

The poster is not named as, unlike Nadiya’s and Alam’s, his is not a public status.