That terrible ‘70s show

Inflation reflects a society that is coming apart at the seams, where those in charge have abdicated their responsibility, where an honest person cannot afford "Roti, Kapada aur Makaan"

The 1970s was a great decade for movies involving a certain kind of character — usually a young man, all‑too‑often angry, filled with a righteous rage and a nihilistic vitality, in Billy Joel’s words, one who refuses to bend, refuses to crawl. Men like Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry, Charles Bronson in Death Wish, and Robert De Nero in Taxi Driver, Razzak in Rangbaaz.

Amitabh Bachchan is, of course, practically synonymous with the words "angry young man". His fictionalised portrayal of Haji Mastan (aka Sultan Mirza) in "Deewaar", a real-life don of Bombay's underworld, being perhaps the most iconic of such roles.

Anti-heroes and angry young men —the 1970s were a more sexist time, and angry young women were very few (though there were more than one example in Bangladesh, about them some other time) —resonated with audiences all over the world, because the 1970s was a time when, across the world, there was socio-economic instability and malaise.

It was a time of high inflation, and economic stagnation.

Whereas GDP statistics are not well understood, and unemployment or stock prices affect only some sections of the society, one economic indicator that is readily understood, and disliked, by everyone, everywhere in the world is high and rising inflation.

Inflation means rising cost of living. When inflation outpaces wages, there is a cut in real income. When inflation is high, savers' wealth is devalued. Rising or volatile inflation makes it difficult to plan for the future, affecting investment, employment, and incomes. The effects on people's living standards are palpable.

Inflation also feeds into social malaise and discontent in less tangible ways. Historically, high and rising inflation had been the times when rulers debased their metallic coins, often to pay for ruinous wars. In a modern economy, volatile inflation is often the result of macroeconomic mismanagement.

There is probably something akin to folk memories of inflation being associated with a society that is coming apart at the seams, where those in charge have abdicated their responsibility, where an honest person cannot afford "Roti, Kapada aur Makaan" (a 1974 blockbuster about, you guessed it, young men who cannot lead a decent life through education and hard work).

Inflation and stagnation, the stagflation, of the 1970s created the zeitgeist that gave us the onscreen anti-heroes and angry young men.

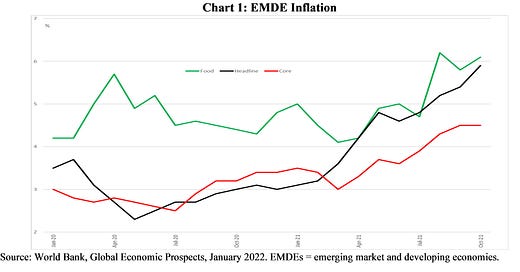

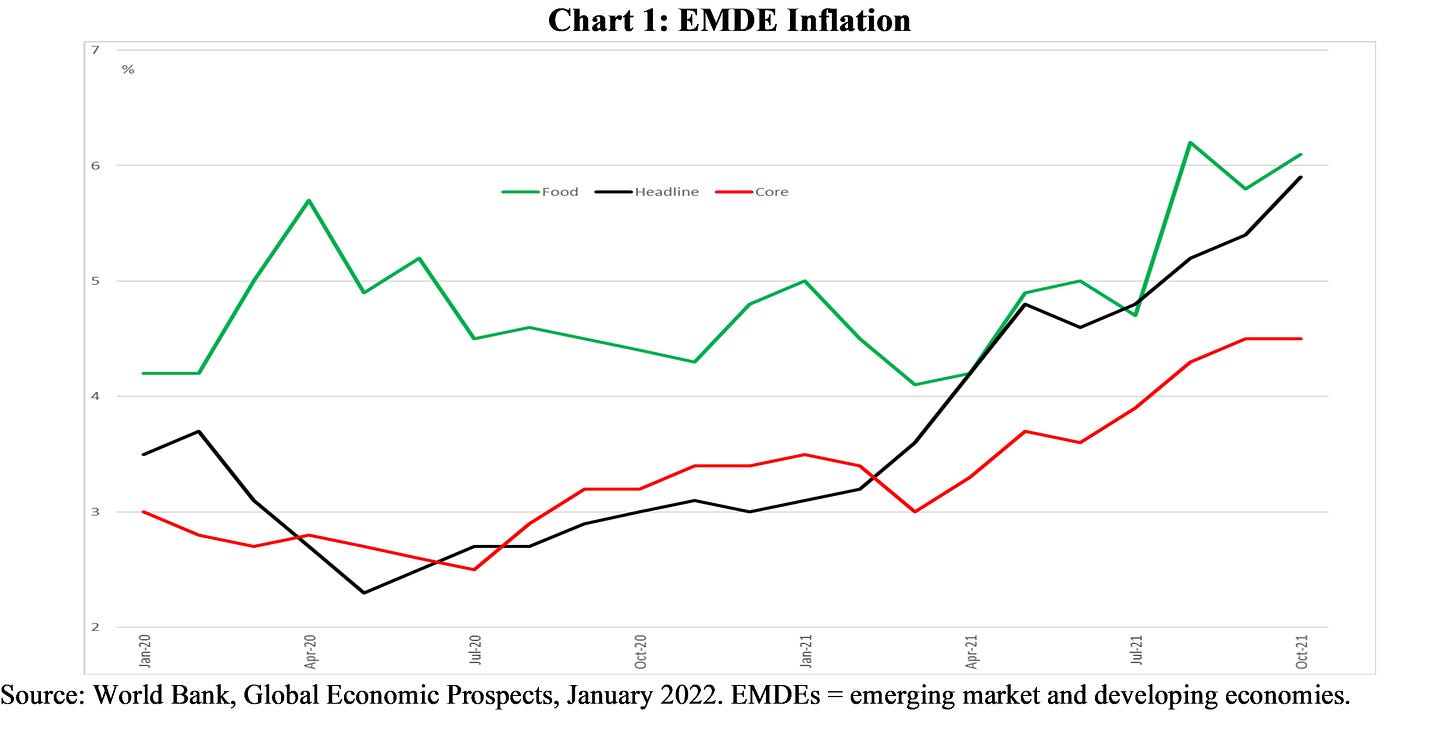

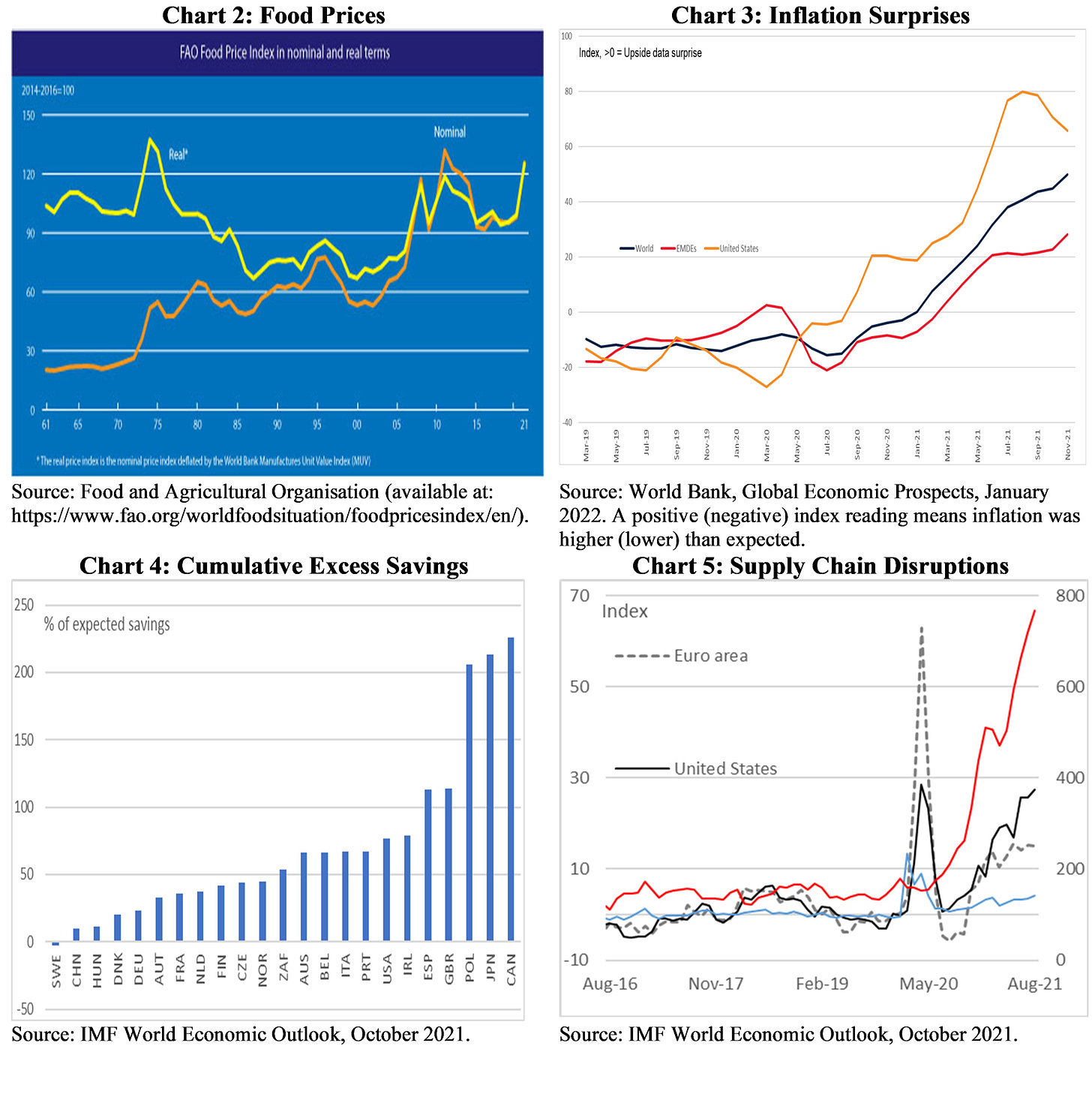

Inflation is rising again across the world, often to rates not seen in decades. For example, inflation in the US hit 7percent in the year to December of 2021, a rate not seen in nearly four decades. In emerging markets and developing economies, the rise in inflation has been broad-based. Food price inflation is running at an elevated level, but as Chart 1 shows, core (that is, non-food, non-energy) inflation also picked up in 2021.

Adjusted for income, food has not been this expensive since the 1970s (Chart 2). Policymakers and investors alike have been surprised by the inflation (Chart 3), which has been thus far driven by supply and demand mismatches as the world economy recovers from the pandemic.

Households in the developed world have built up a large amount of savings in the last couple of years (Chart 4). Supported by government handouts and unable to spend freely because of recurring Covid-19 waves, these cashed up consumers have gorged on online shopping. Global logistics and supply chains have not been able to handle the high demand, causing a logjam of ships in ports around the world (Chart 5).

Inflation has also been ticking up in Bangladesh, to cross 6 percent in the year to December 2021, with non-food price inflation hitting 7 percent over that period (Chart 6). Compared to the government forecast of 5.3 percent inflation for the financial year 2021-22, which is also the Bangladesh Bank’s monetary policy target for the year, this rate of inflation should raise alarm bells. Inflation is also tracking ahead of the IMF’s October 2021 forecasts of around 5½‑¾ percent range on an annual basis, which is moderate by historical standards (Chart 7).

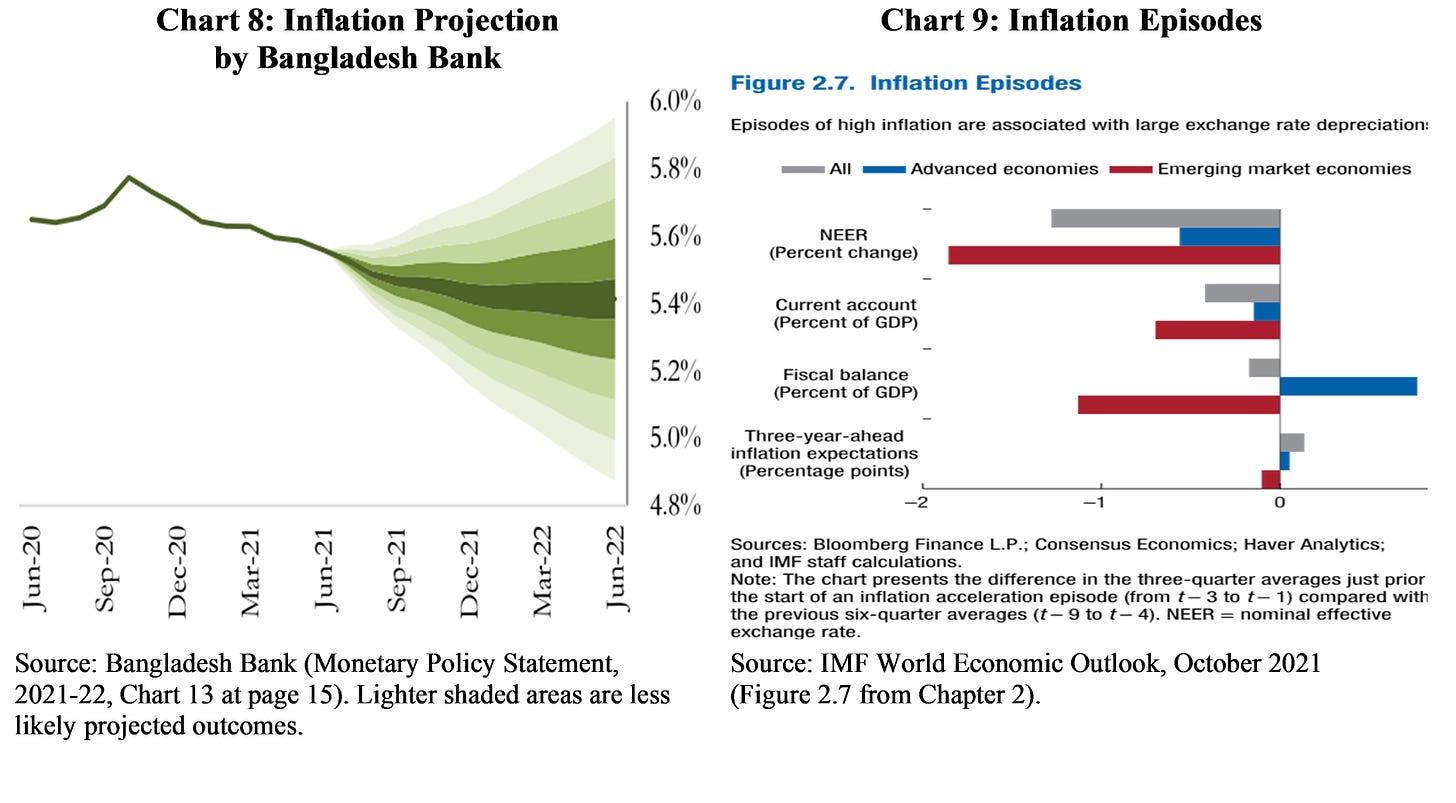

Further, Chart 8, reproduced from the Bangladesh Bank’s Monetary Policy Statement for 2021-22 financial year shows that inflation of 6 percent was considered an extremely unlikely outcome by the central bank only a few months ago.

That is, much like elsewhere, inflation in Bangladesh is already surprising on the upside, and the benign inflation forecasts, whether by the Bangladesh Bank or the IMF, bear considerable upside risks.

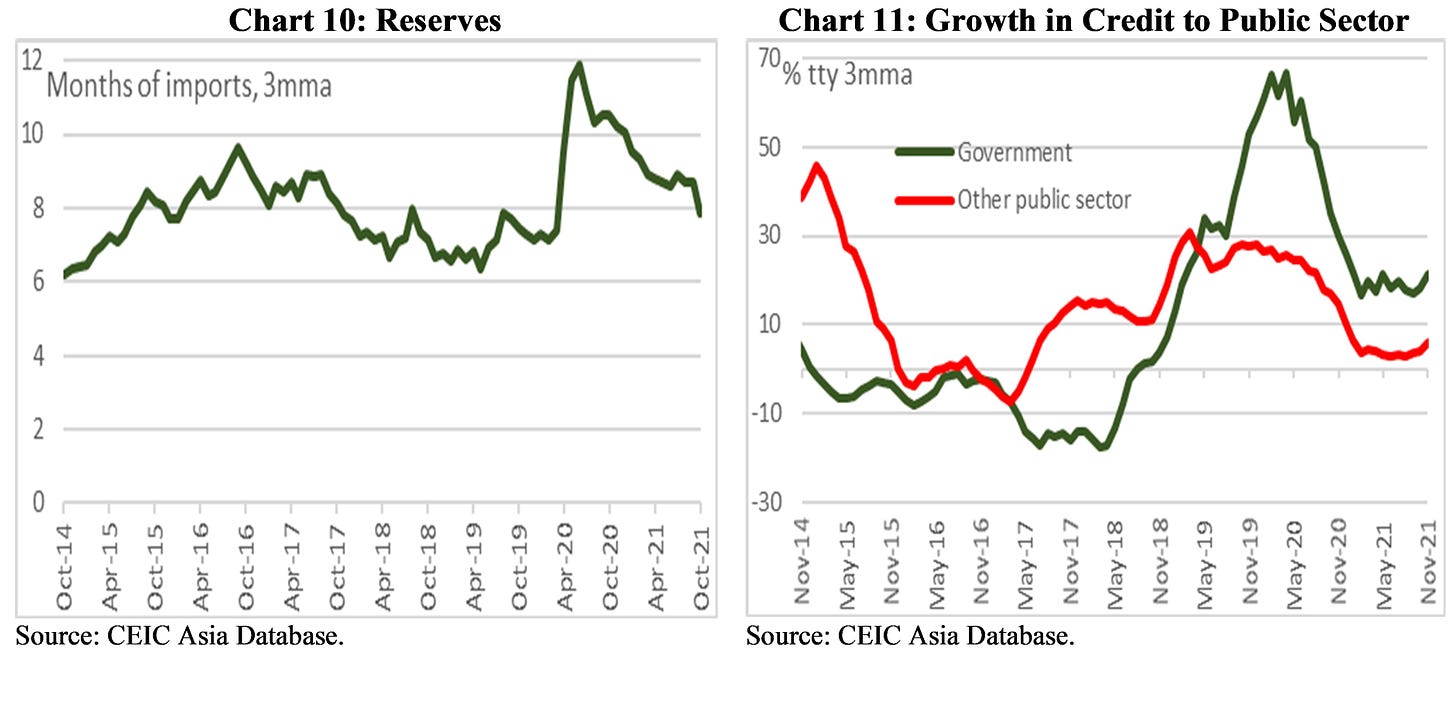

Drawing on macroeconomic theory and empirical research by the IMF, it is possible to consider a few indicators to gauge the extent of these upside risks to inflation. High inflation episodes in emerging market economies have historically been associated with exchange rate depreciations and twin deficits in external and fiscal accounts (Chart 9).

Let us consider the external sector first.

A depreciation of the exchange rate increases the price of imports. As developing countries typically import food and intermediate goods such as fuel and machinery, depreciations usually fuel inflation.

To complicate matters further, inflation can also add to depreciation pressures. For example, in the absence of any change in the nominal interest rate, higher inflation means a country's financial instruments would yield a lower real yield, which might lead to capital outflow, putting pressure on the exchange rate.

Of course, if financial markets deem a country's current account deficit unsustainable, its exchange rate would be hit, potentially creating a doom loop between the currency and inflation. History of countries such as Turkey and Argentina abound with such vicious cycles.

So, is Bangladesh at risk of a sharp exchange rate depreciation in 2022?

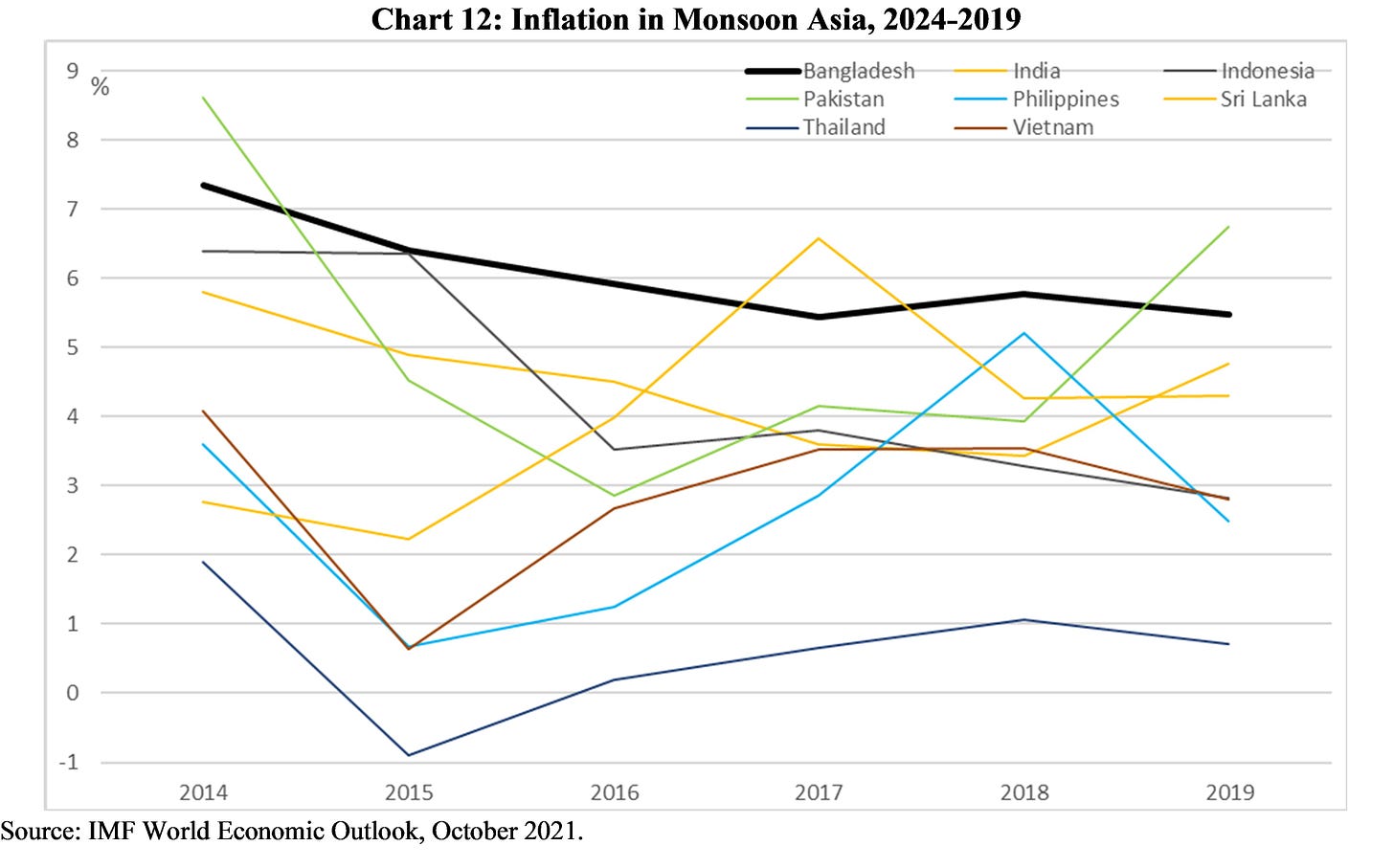

One common metric to judge whether a developing country's exchange rate is likely to remain stable is to look at how many months of imports can be bought with the foreign exchange reserves held by a country's central bank.

If the reserves dips to an amount that cannot pay for at least three months of imports, the country's currency might face pressures to depreciate. Chart 10 shows that Bangladesh Bank's foreign reserves are far above that three-months-of-imports threshold.

Like any economic indicator, this metric needs to be assessed against a broader context, and not be judged in isolation.

Higher than expected inflation in the United States means monetary policy there will tighten in 2022. The last time the US Federal Reserves tightened monetary stance in 2013, it caused a bout of instability in the emerging markets. There is a risk of a repeat of the so-called taper tantrum. Should there be financial instability in the emerging markets, Bangladesh might come under scrutiny in spite of the seemingly adequate level of reserves.

It is against that backdrop one must consider the recent IMF report that $7 billion of the central bank's foreign reserves are misclassified.

Perhaps it was just a matter of technical error. But when the finance minister openly muses about using the reserves to pay for government expenditure, markets may start worrying. If such musings happen even as the growth in credit to the government runs at a high pace (Chart 11), markets may start acting on that worry. And if this happens in the lead up to an election, it may have disastrous results.

The link between fiscal policy and inflation cannot be considered without an understanding of the political economy. It is worth thinking about these links step-by-step.

A government typically borrows heavily when it is not raising enough taxes to pay for its expenditures. There is nothing wrong with debt-financed budget deficits in and of itself. And under certain situations, it may even be the sensible policy course to pursue.

However, if the government continues to face financing difficulties, it might start borrowing from not just the commercial banks, but also the central bank. Central bank financing of the budget deficit means a government has essentially run out of all other options, and is looking at the barrel of hyperinflation.

Of course, that is an extreme outcome, but one that has happened in recent years in Venezuela and Zimbabwe. There is no suggestion that this is a realistic ground for worry for Bangladesh in 2022. At least one hopes that so. There are, however, other links between inflation and fiscal stance that should be of concern for us.

Expansionary fiscal policy in the form of stimulus or support to households and firms might put a floor under demand in times of recession or severe downturns. However, when an economy is already booming, or when economic activities are constrained by supply disruptions and bottlenecks, fiscal expansion is likely to result in inflation. For example, cashed up households meeting gummed up supply chains —that is the oversimplified story of the current global inflation.

As it happens, there is a risk of fiscal expansion in Bangladesh, not for any macroeconomic reason, but because of politics.

According to a study by IMF's Christian Ebeke and Dilan Olcer of Riksbank, government expenditure typically rises ahead of elections in developing countries, and the pre-election party usually ends in post-election hangovers. The authors study how public finances vary over electoral cycles in 68 developing countries during the 1990-2010 period. They show that in the year of the election, government spending on salaries, subsidies and procurement — that is, stuff that can help government get a popularity boost or facilitate patronage — rises.

After the election, however, the time of reckoning arrives, and the expenditure is typically paid for by cutting public investment and raising taxes such as tariff and import duties. Not only is the initial expenditure typically wasteful, the way it is paid for is usually harmful for the economy's long-term growth prospects.

How is this finding relevant for Bangladesh?

Well, in the lead up to the 2018 election, Bangladesh was experiencing strong growth on the back of export and remittance earnings, and there was no obvious macroeconomic case for a fiscal expansion. Yet, public expenditure did contribute to demand, pushing the growth rate to a pace that might have been faster than the economy's supply-side potential.

How do we know that growth was running too hot?

Well, in the five years to 2019, Bangladesh experienced higher inflation than neighbours in Monsoon Asia (Chart 12), and higher inflation is what one might expect with expansionary fiscal policy in the face of supply constraints.

As we head into the 2023 election season, the economy may or may not be benefitting from another round of exports or remittance boom. However, in an already inflationary environment, with significant supply constraints caused by the pandemic, politically motivated fiscal stance might prove very costly indeed.

A rerun of the stagflationary 1970s —the economic malaise of slow growth and inflation — could well be a major risk to the economic outlook.

Images of the 1970s — of longhaired men with shirts unbuttoned to the navel, in the company of buxom, bell-bottomed women with hair split in the middle, beating up ugly brutes with long sideburns, to the beat of a funky tune — that stuff is great on our screen.

Let us not have any other 1970s rerun.

A shorter version of this piece was first published in The Business Standard.