Inflation: the macro (political) economic perspective

Speaking notes for the Voice for Reform event

Greetings and acknowledgement of the shaheeds of the Monsoon Uprising.

I make two points.

First, there is a difference between high prices and high inflation. High prices reflect microeconomic factors — supply and demand for specific goods or services, which could mean prices go up or down. High inflation, on the other hand, reflect macroeconomic policy settings — monetary policy as reflected in the interest and exchange rates, and fiscal policy as reflected in revenue, expenditure, and financing decisions. Ultimately, macroeconomic policy settings reflect the underlying political economy and the growth model.

Second, what can be done to reduce inflation? In the near term — over the next six to nine months — tighter macro policy to stabilize the exchange rate will help drive inflation down to 6-7%. In the longer term, to reduce inflation further, would require a recalibration of the political economy, which is an open question.

Bangladesh has been a high price country. Over the summer of 2023, one kilogram of rice was more expensive in Dhaka than other subcontinental megacities. The reasons are microeconomic that I leave to others (Md Helal Uddin of Dhaka University, Waseem Alim from chaldal.com).

Bangladesh has also been a high inflation country. Over the 2014-19 period — before the pandemic and other shocks, when global oil and food prices were low, global economy was booming but inflation was low everywhere, and the taka was relatively stable — Bangladesh was experiencing annual inflation close to 6%, higher than 2-4% in our neighbors.

We were running 6% inflation because this was the result of the underlying growth model of the Hasina regime. Since the 1980s, our economy had two major drivers: RMG exports and remittances. Hasina regime added the megaprojects and poorly run banks to the mix. The result was loose macroeconomic policy setting, with demand pacing ahead of supply and inflation creeping up.

Moving to what is to be done — the exchange rate stability and higher real interest rate should reduce inflation from the current 9-10% to 6-7% by mid-2025.

Like other economies, Bangladesh experienced an external shock in 2022 with the Ukraine War and rising interest rates in the advanced economies. The result was a depreciation of the taka. But taka depreciated much more than the relatively stable countries in Monsoon Asia.

This was because of policy choices made by the fallen regime. Faced with the external shock, the standard way to keep the currency stable is to raise interested rate. In Bangladesh interest rates were capped, resulting in negative real borrowing rates for an extended period of time. There was no policy rationale for this, but clear political economy explanation — money was cheaper than free for those who could get it, and they took it and siphoned a lot of it abroad ahead of the January 2024 election. This created a depreciation pressure on taka which manifested itself in the informal hundi market. As formal remittances remained weak, reserves declined and taka depreciated, raising inflation. The regime responded with import control, which created further supply chain problems and fueled inflation further.

The whole thing ultimately reflected policy choices made by the fallen regime.

The appropriate policy response now, and the one being pursued by the Bangladesh Bank, is to reverse the above dynamics. The real interest rate needs to rise further. The authorities are allowing the market to determine borrowing and lending rates given policy rates — that is, a modern monetary policy framework is finally being implemented. Meanwhile, taka has been stable since even before the Monsoon Uprising, and remittances have been booming since August, suggesting the expectation is for currency stability in the near term. If this continues, and barring any adverse shock, inflation should gradually decline to 6-7% over the coming months (Governor Mansur Ahsan expects by June 2025).

Of course, there is a trade off here. Reducing inflation through higher interest rates may well mean a slowdown in economic growth. However, strong remittances, and hopefully a recovery in exports, should cushion the economy from rising interest rates to some extent.

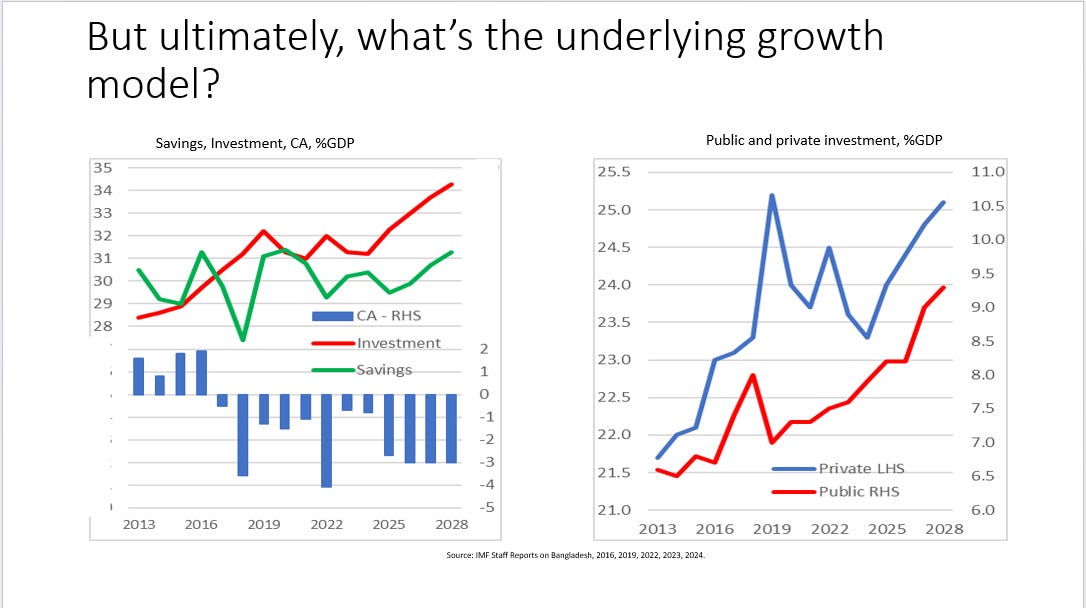

Governor Ahsan says he wants to reduce inflation even further. To get to 4-5% inflation in the longer run, however, is probably not consistent with the old growth model of twin deficits driven by externally financed public investment. Even if the old IMF program was fully implemented by the fallen regime, the forecasts were for significant current account deficit into the late 2020s. That deficit would have left the currency vulnerable to depreciation pressures and risks of higher inflation.

To reduce inflation below 6% in the long run would require a resetting of the underlying growth model. It’s not that public investment is inherently bad — far from it, good investments can expand the economy’s productive capacity, increase growth without raising inflation. But this was not the case under the fallen regime.

The broader point perhaps is that we should have a discussion about what kind of growth model do we want to see in Bangladesh.

Further reading

History's Inflation Lessons by Ari and Ratnovski

Anil Ari and Lev Ratnovski, 1 Dec 2023

Political settlement and constitutional reform in post-autocratic Bangladesh

Faiz Ahmad Taiyeb, 26 Aug 2024

সৌরবিদ্যুতে ডলার ও জমি দখলের প্রতিযোগিতা!

ইসমাইল আলী, 5 Sep 2024

Syed Akhtar Mahmood, 10 Sep 2024

প্রক্রিয়া জটিল হলেও বিদেশে পাচার হওয়া অর্থ ফেরত আনা যাবে

ইফতেখারুজ্জামান interviewed, 16 Sep 2024

Britain asked to investigate assets linked to ousted Bangladeshi regime

Benjamin Parkin, Chris Cook, Cynthia O’Murchu and Lucy Fisher, 18 Sep 2024

পদ্মা ব্যাংক থেকে টাকা বের করতে যেভাবে জটিল জাল বিছিয়েছিলেন চৌধুরী নাফিজ সরাফাত

জেবুন নেসা আলো, 18 Sep 2024

Inside the lives of RMG workers

Tahira Shamsi Utsa, 18 Sep 2024

Atif Mian, 23 Sep 2024

‘Administered prices don’t work’

Hossain Zillur Rahman interviewed, 25 Sep 2024

Between a rock and a hard place: Why are RMG workers prompting constant debate?

SM Abrar Aowsaf, 26 Sep 2024

ব্যবসা গোটাচ্ছে দেড় শতাধিক কম্পানি

মিরাজ শামস, 9 Oct 2024

> It’s not that public investment is inherently bad — far from it, good investments can expand the economy’s productive capacity, increase growth without raising inflation. But this was not the case under the fallen regime.

Other than the giant cricket stadium that looks like a boat, what public investments do you think were unproductive?