Anatomy of a Potential Crisis

As Bangladesh becomes richer, its ability to finance budget-deficits through grants and concessional loans will diminish

Sri Lanka is a much richer country than Bangladesh. Pakistan is a fledgling democracy with regular, free and fair elections, an independent judiciary, and a thriving media scene. Both countries are in economic crisis. Sri Lanka is facing down the barrel of bankruptcy, and Pakistan may not be far behind.

The causes and consequences of these countries’ economic woes present cautionary tales for Bangladesh. Using a set of charts, let’s try to unpack what’s going on in each country, and what lessons and warnings can be inferred.

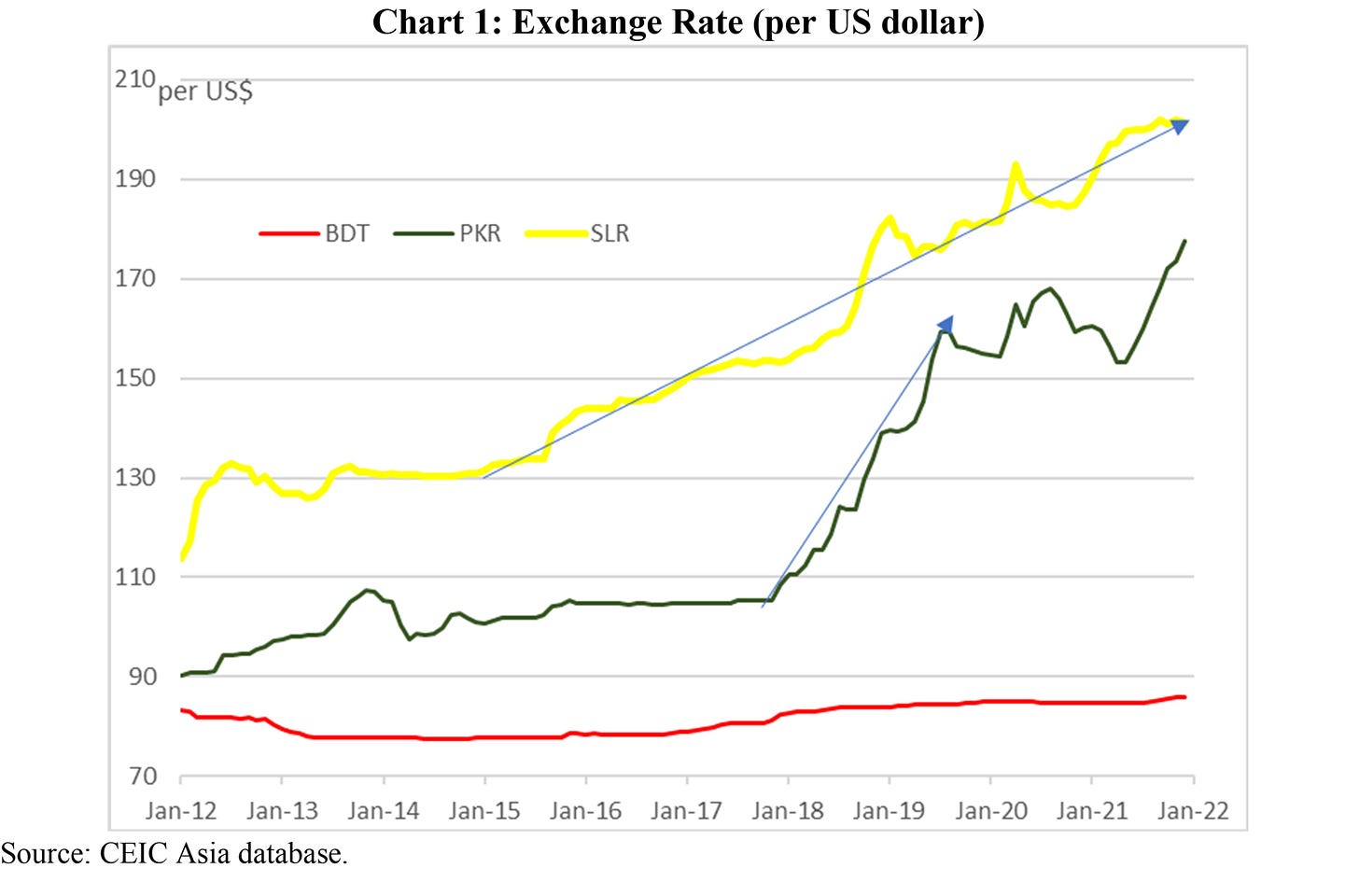

Let us begin with the exchange rates. Chart 1 shows that the Sri Lanka rupee has been depreciating steadily over the past seven years, from about 130 per US dollar in late 2014 to over 200 at the end of 2021. The Pakistan rupee had a sharper fall in 2018-19, from 153 to 180 per US dollar. In contrast, the taka has been steady between 83‑87 per US dollar over the past decade.

Exchange rate stability matters immensely for developing countries. A depreciating currency makes imports dearer. Since developing countries typically import essentials such as food and fuel, and intermediate goods that go into the production process, more expensive imports add to general cost of living pressures. Further, depreciations make foreign currency denominated debt more expensive, crimping the government’s ability to spend on public services as debt service takes up more of the budget.

That is, contra Tim Worstall, there are many good reasons why a developing country might want to stabilise its currency. The desire of the governments of Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, to avoid depreciation is completely understandable. The questions to ask are, what’s behind the depreciations, and what, if anything, could the respective governments do?

A depreciating currency means there is more demand for foreign currency in that country —to pay for imports, and service foreign debt —than supply —from exports and remittance earnings, and foreign investment. Further, expectations of a future depreciation can trigger a run on the currency, causing a depreciation today. When a country’s current account deficit is considered unsustainable, it can set off depreciation pressures.

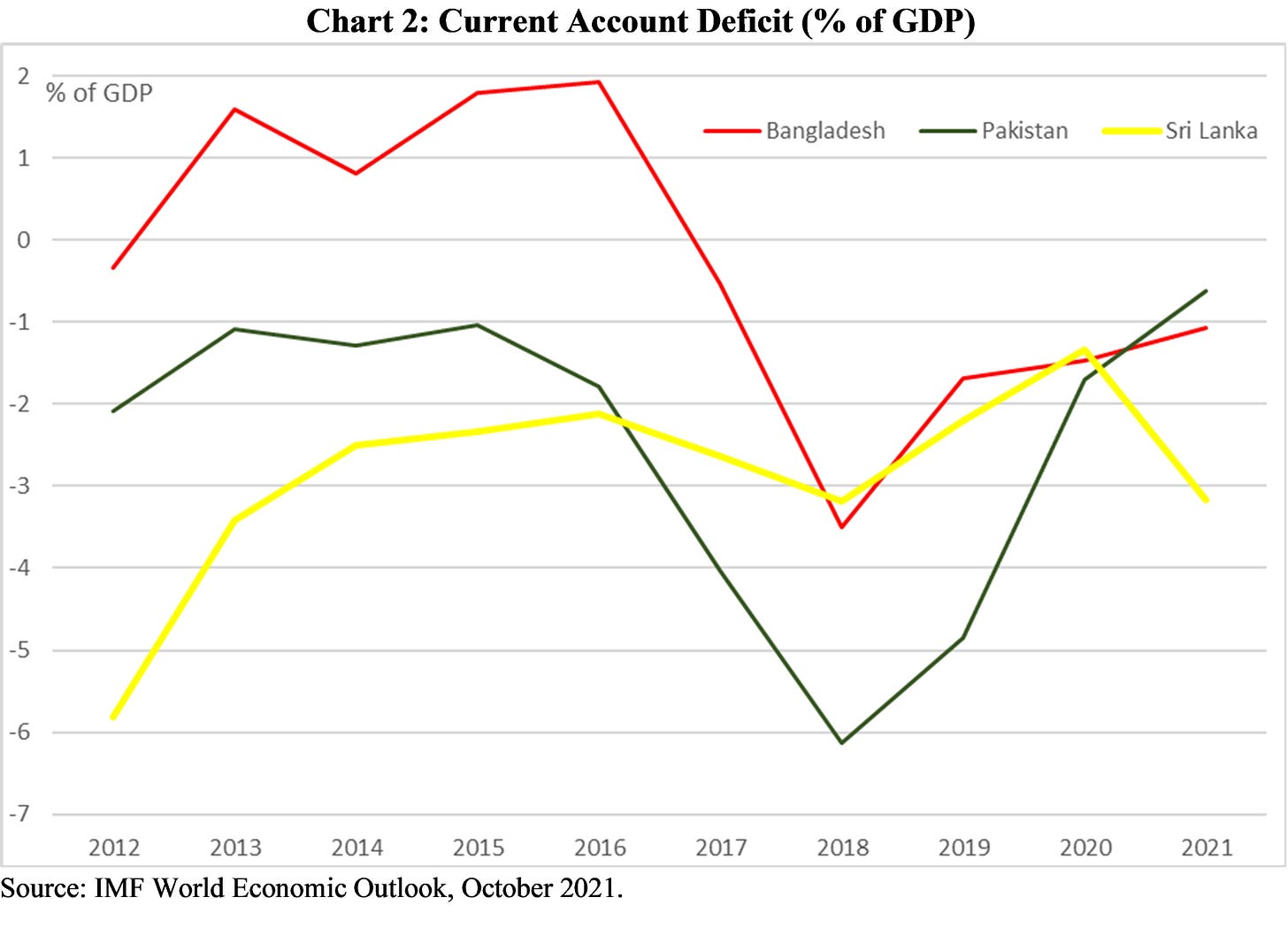

Chart 2 shows that both Pakistan and Sri Lanka have been running current account deficits for the past decade, which is likely to have contributed to the depreciation of the two currencies. In Pakistan, for example, the current account deficit widened sharply, by about 5 percent of GDP, during 2015-18, setting the stage for the sharp depreciation of 2018-19.

However, there is more to the story. Pakistan’s current account deficit has been narrowing since 2018, but the currency remains unstable. More interestingly, Bangladesh’s current account also experienced a 5 percent of GDP turnaround during 2015-18 —from a surplus of nearly 2 percent of GDP to a deficit of 3 percent of GDP. In fact, in 2021, Bangladesh’s current account deficit was wider than Pakistan’s. Yet, the taka has remained stable.

To understand the different fates of the currencies, we need to unpack what has been driving the countries’ current accounts.

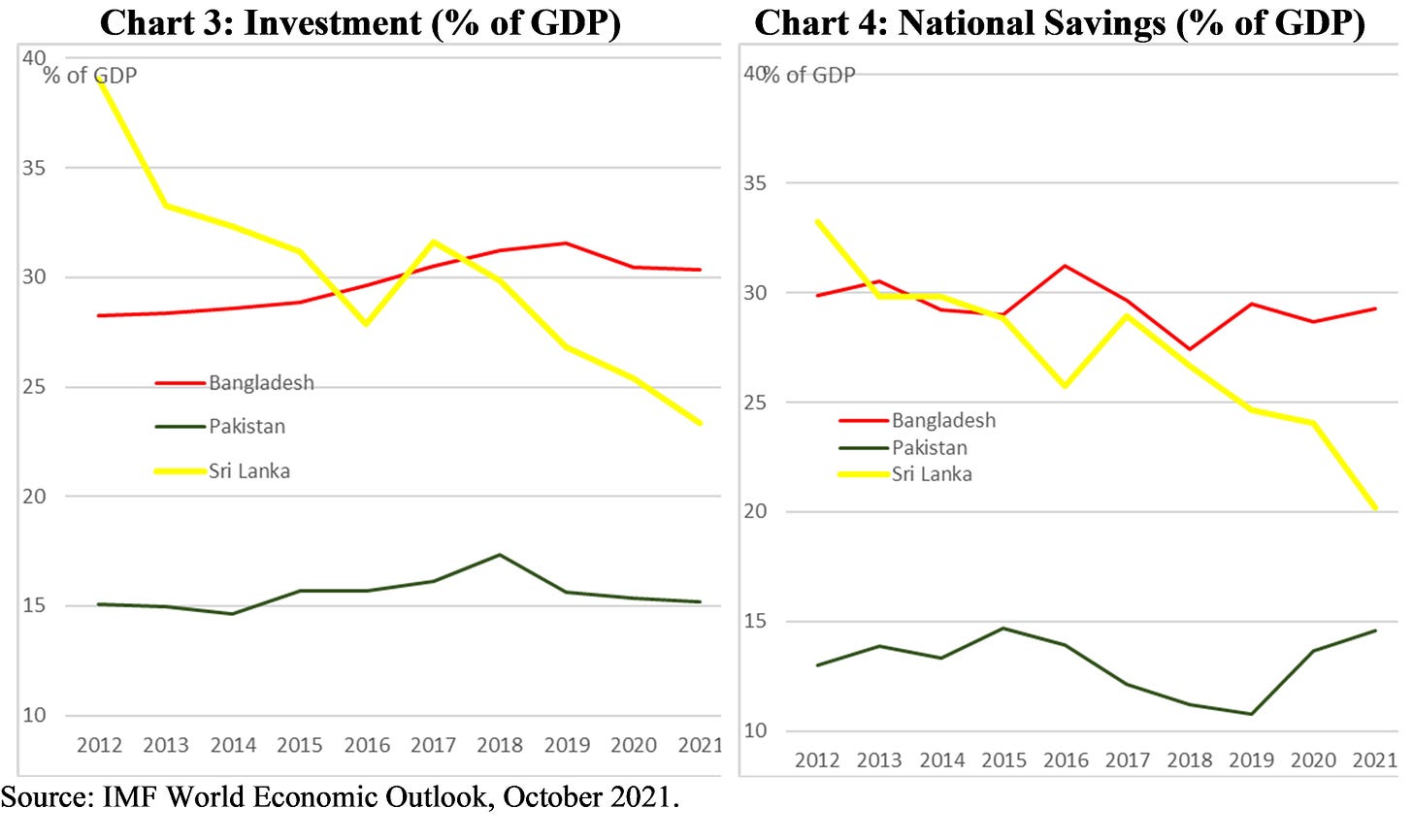

A country’s current account represents the difference between its investment and national savings. When the investment in a country is more than its national savings, the difference is made up by import of foreign capital or drawdown of foreign exchange reserves —that’s the current account deficit. Conversely, when the country’s savings are higher than investment, it exports capital overseas, or accumulates foreign reserves —that’s the current account surplus.

Seen from this prism, a current account deficit is not necessarily a bad thing if it is driven by high quality investment, while a current account surplus is not necessarily a welcome development if it is caused by a lack of worthwhile investment projects in the country. It all depends on the details.

Charts 3 and 4 explore the investment and savings patterns in the three countries.

Let’s start with Pakistan, which is a low savings, low investment country. During 2015-18, it had experienced a pick up in investment even as its savings dipped. As the Chinese investment in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor poured in, imports soared because the country needed more capital goods, while the increasingly affluent urban classes gorged on imported consumer items. The financial markets judged that Pakistan couldn’t sustain the investment boom while its savings remained so low. That is, its current account was assessed as unsustainable, and its currency tumbled.

Sri Lanka had much higher savings and investment relative to GDP than Pakistan. But both investment and savings have been dwindling for the past decade. When savings and investment both fall steadily for a decade relative to a country’s GDP, chances are that its people are not optimistic about its future. It’s not a surprise then why the financial markets might assess its current account deficit to be unsustainable.

In contrast, Bangladesh is a comparatively high investment high savings country. Yes, savings declined relative to GDP during the 2015-18 period, while investment increased. But both savings and investment remained high relative to GDP. And the financial markets has, thus far, assessed the current account deficit to be sustainable.

One lesson to be drawn from the experiences of Sri Lanka and Pakistan therefore is that national savings matter.

National savings is composed of savings of the private sector —households and corporates —and the public sector —the government and the state-owned enterprises. Government policies and institutional settings of a country affect private sector balance sheets as well as the finances of the state-owned enterprises. But those things are also affected by broader factors including demography, culture, and technology. The budget, however, is more directly within a government’s control. All else equal, if the budget deficit worsens, it is harder to sustain a current account deficit.

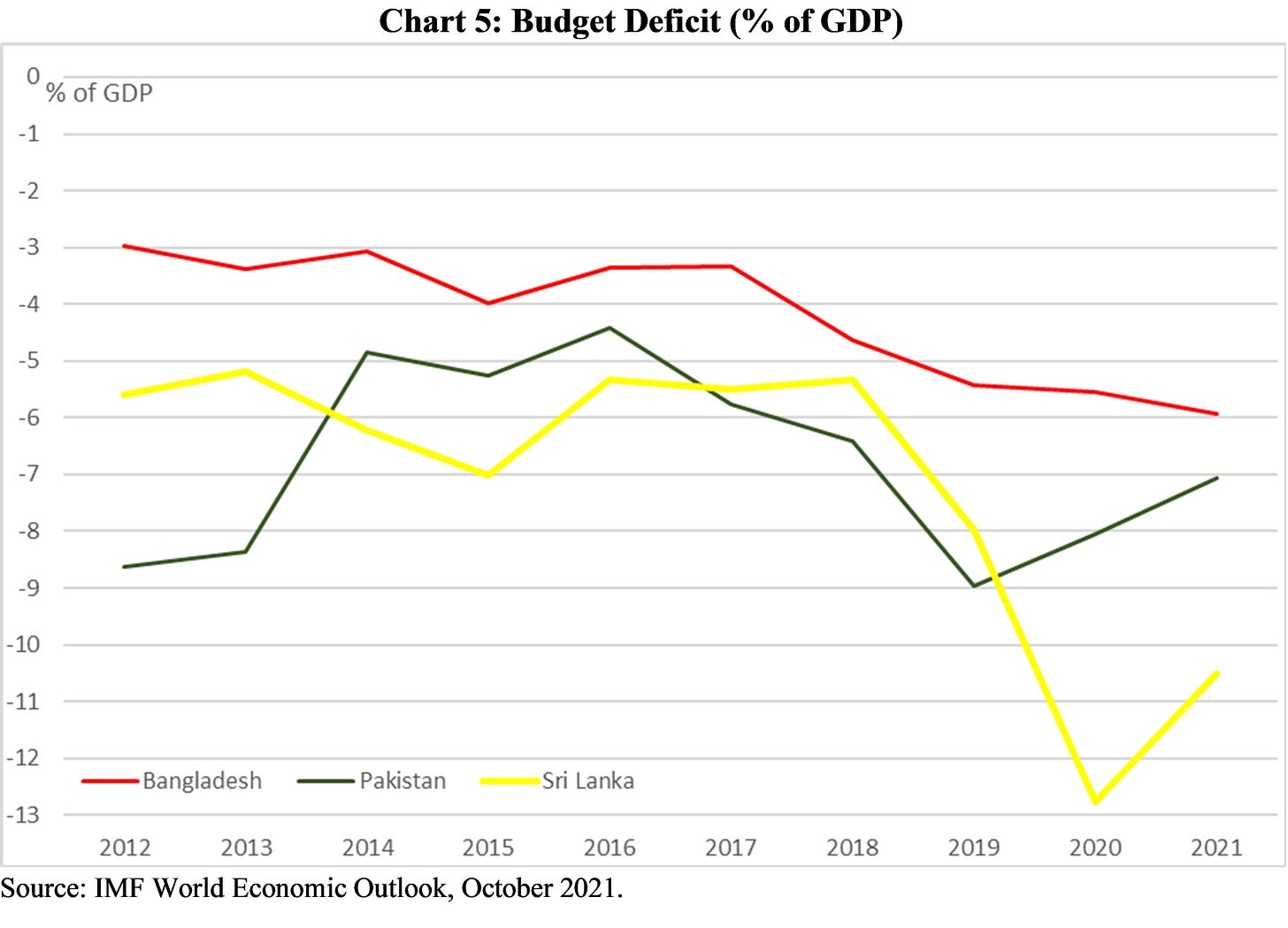

Chart 5 shows that not only were the governments of both Pakistan and Sri Lanka running large budget deficits for the past decade, the deficits started widening even before the pandemic hit. That is, fiscal policies in both countries were making their current accounts unsustainable. Here is another lessons then —budget deficits matter.

Budget deficit had started widening in Bangladesh too before the pandemic, reaching over 5 percent of GDP in 2019, similar to what Pakistan and Sri Lanka had run in the mid-2010s.

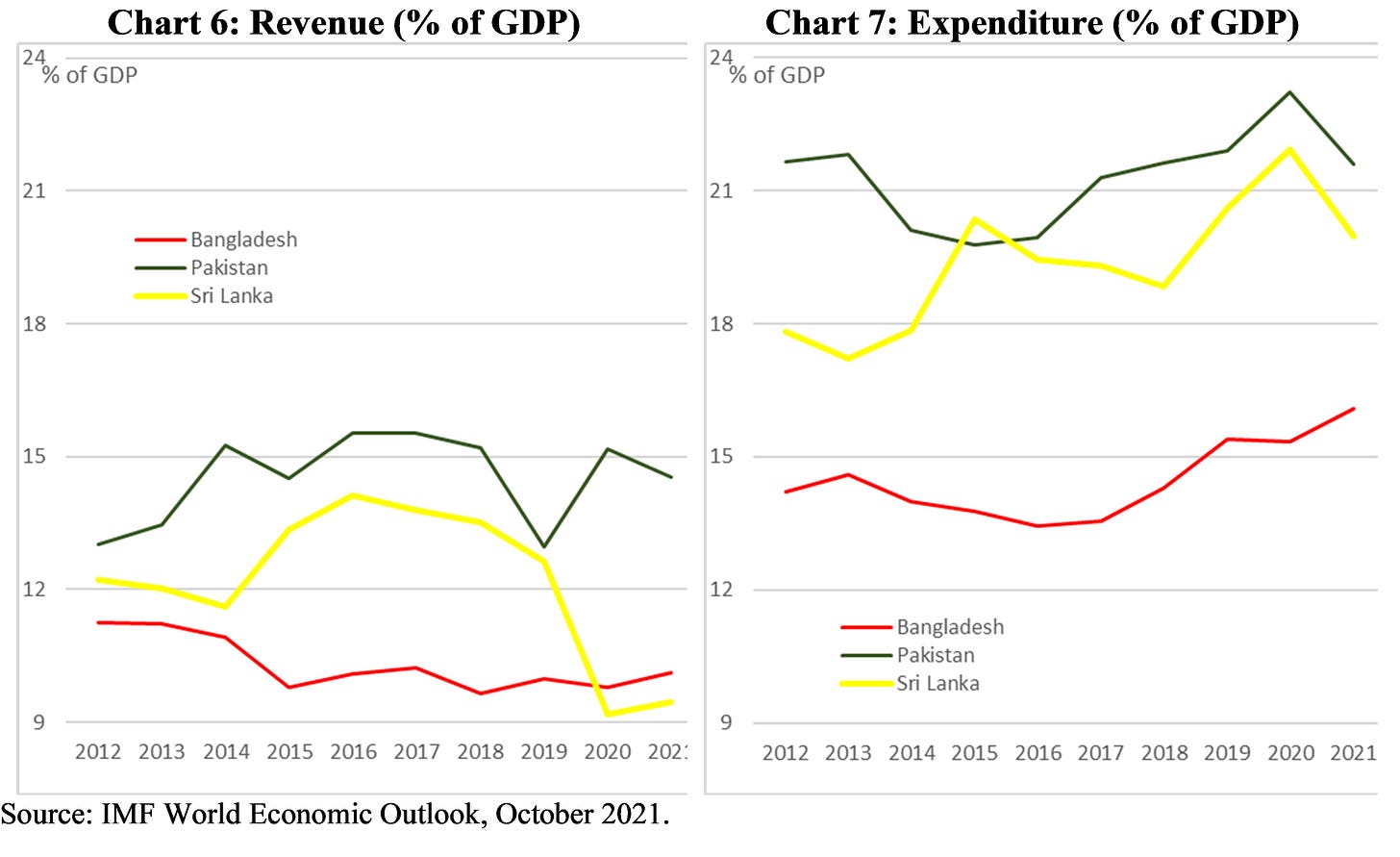

To understand the lessons the two countries’ subsequent experiences might have for us requires an analysis of government revenue and expenditure trends, which is done in Charts 6 and 7.

These two charts show that the governments of Pakistan and Sri Lanka usually raise more revenue, relative to GDP, than Bangladesh. In fact, Bangladesh has one of the lowest revenue-to-GDP ratios in Monsoon Asia, limiting the state’s ability to provide basic services or maintain law and order.

As bad as that is, of more immediate concern is the fact that Bangladesh government’s expenditures had started creeping up well before the pandemic. While public expenditures, relative to GDP, remain lower in Bangladesh than Pakistan and Sri Lanka, given the perilous state of revenue generation, there really isn’t much room for expenditures to rise before financing the deficit becomes an issue.

And that takes us to the issue of how the three governments had financed their respective deficits over the years.

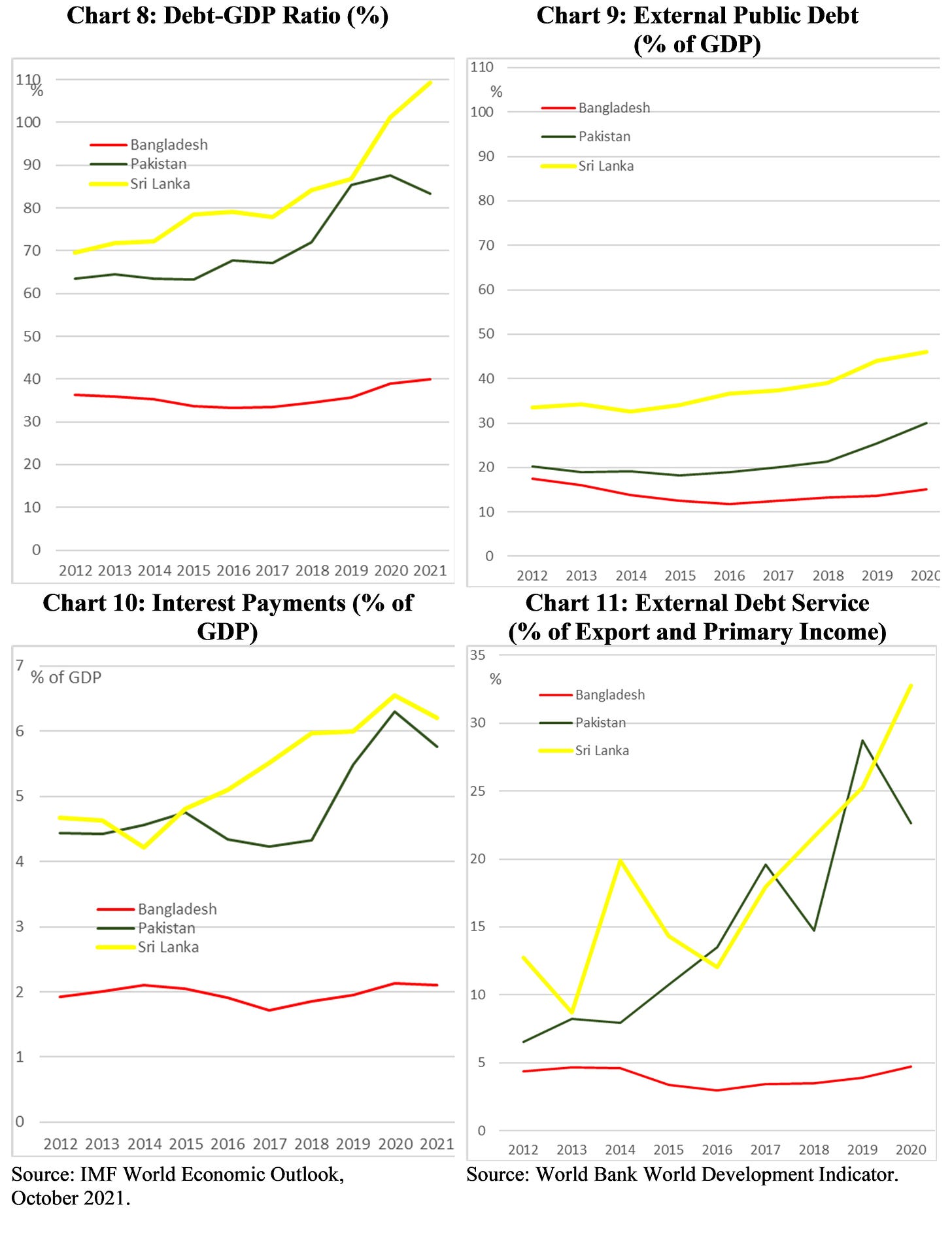

In Bangladesh, successive finance ministers between AR Mallick and AMA Muhith tried to run a fiscal strategy where much of the non-development expenditure is paid for by the meagre revenue raised by the government, in the process, inadvertently turning Bangladesh into a libertarian wet dream not because of a conscious policy choice but out of necessity. Under this strategy, much of the deficit had reflected development expenditure, which were financed by grants or concessional loans. As a result, debt-to-GDP ratio in Bangladesh had remained stable, as had public debt owed to foreigners.

As Charts 8 and 9 show, this has not been the case in Pakistan and Sri Lanka. In both those countries, deficits have been financed by debt. In Sri Lanka, a large proportion of the new debt has been to foreigners. And as these countries have accumulated debt, so has risen the cost of servicing the debt.

As Chart 10 shows, interest payments on public debt amounted to 4-5 percent of GDP in Pakistan and Sri Lanka, compared with around 2 percent in Bangladesh. Put differently, while governments of those countries raise much more revenue from their citizens than is the case in Bangladesh, much of that extra revenue is spent on paying interests. Meanwhile, debt keeps piling up.

Further, as the stock of external debt rose in these countries, so did the call on foreign currency to service that debt. As Chart 11 shows, by 2020 nearly a third of the foreign currency earnings of Sri Lanka and a quarter of that of Pakistan had been spent on servicing debt to the foreigners. In contrast, less than 5 percent of Bangladesh’s foreign currency earnings had to be spent on servicing foreign debt.

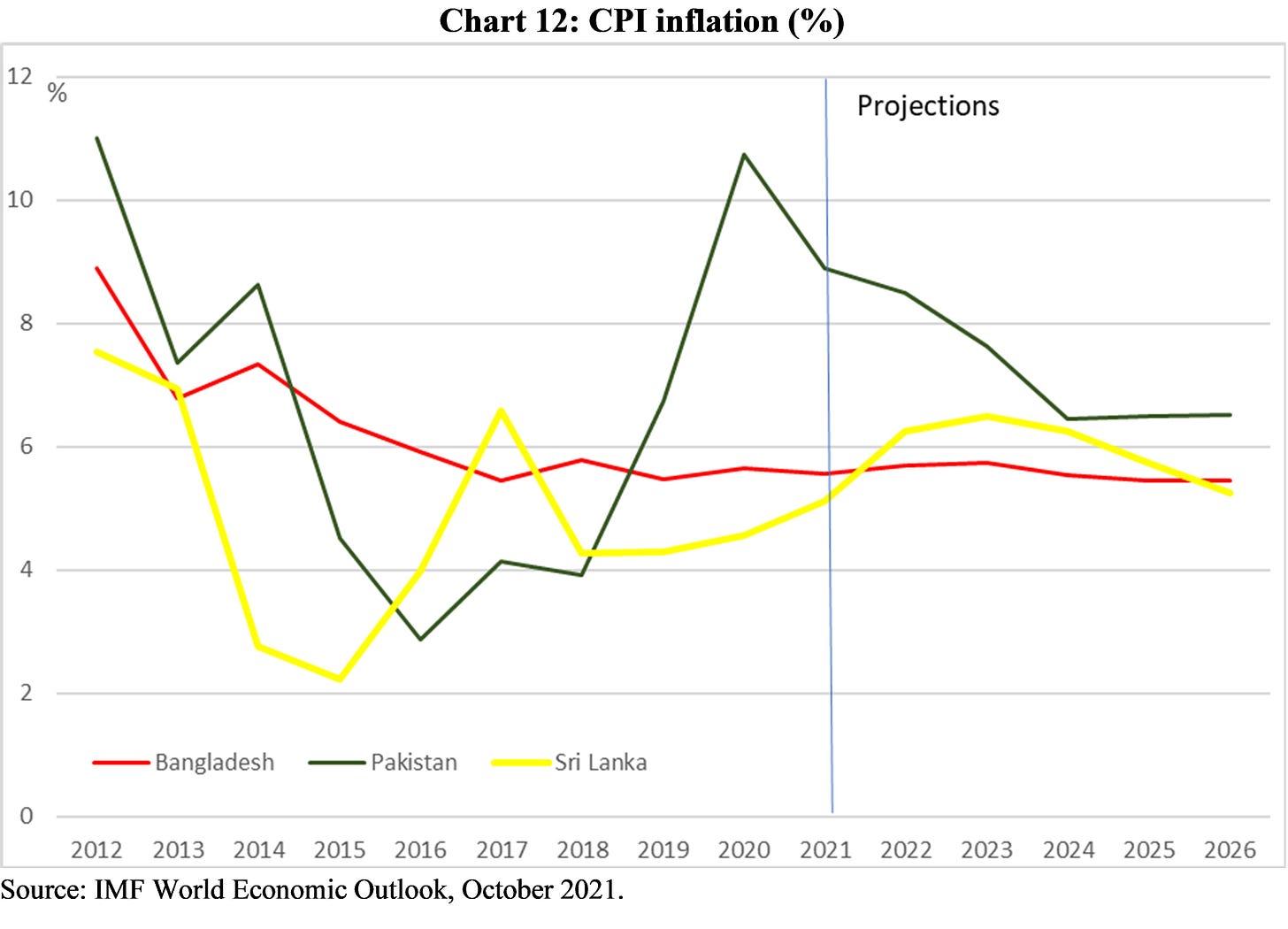

When the exchange rate depreciates, the whole dynamic worsens. More foreign currency is needed to pay the foreign creditors. As the budget deficits widen, the governments need to scrounge for more financing. And so it goes, until the government runs out of all other options, and starts borrowing from the central bank. That final resort, of printing money to pay for budget deficit, leads to runaway inflation.

Fortunately for millions of Pakistanis and Sri Lankans, inflation is expected to remain manageable into the medium term (Chart 12).

Of course, runaway inflation means an economy is already in meltdown. And a meltdown remains a risk for both countries. Typically, faced with a situation such as this, if countries turn to the IMF, the advice is to consolidate public finances —raise taxes and reduce expenditure. In fact, contra Farid Bakht, the IMF regularly recommends fiscal consolidation to rich countries too, including the Americans, who ignore the said advice because they are not facing bankruptcy. Options are rather more limited for Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

The officials of the finance ministries and central banks of Pakistan and Sri Lanka are highly qualified people who understand their predicament. They fully appreciate the conditionalities asked by the IMF and western lenders. They know that alternative finances, from China and others, carry their own costs, which are far less transparent than any western loans would be. These officials know full well that the underlying issue of unsustainable fiscal stance and the vicious cycle of debt is the political economies of these countries —the elite consensus to maintain a large defence establishment in Pakistan, consolidation of a family’s grip on power in Sri Lanka, and a decisive tilt to China in the context of great power rivalry and incipient Cold War 2.0.

Let’s end with the relevance of all this for Bangladesh.

Even before the pandemic, our fiscal discipline had started slackening, while the ability to raise revenue remains low. As the country becomes richer, its ability to finance budget deficits through grants and concessional loans will diminish. That is, fiscal profligacy is likely to become costlier than what has been experienced in the past. Add to that mix the domestic political economy ahead of the election in 2023 and the geopolitics of India-China-US, and alarm bells should go off.

This was first published in the Dhaka Tribune.