An uncertain outlook

The current economic assessments of the international agencies may not reflect how the economy could be evolving

Forecasts of Bangladesh's economy used to follow a predictable, consistent pattern. One could take the assessments of international agencies as a generally correct description of the country's economic reality. This is no longer the case.

Before the pandemic, every summer, the government would claim strong economic growth in the fiscal year about to end, forecast a further pick-up in growth, and ambitious expenditure programs to be paid for by an increase in revenue collection. Experts would question the discrepancy in the ending year's growth figures, which would be quietly revised down a few months later.

In autumn, the international agencies would come out with their forecasts —the Asian Development Bank would usually match the government's numbers, but the World Bank would be quite pessimistic, with the IMF being somewhere in between.

By spring, it would become clear that the government's ambitious revenue targets were not tenable. The government would respond by shelving expenditure programs. By April, the international agencies would assess the economy to be growing at similar pace as previous years. With inflation moderating or stable, and the current account largely in the balance, the steady growth assessment would broadly reflect the reality.

And the whole cycle would be rinsed and repeated.

The pandemic broke this pattern. And the current economic assessments of the international agencies may not reflect how the economy could be evolving. Let's examine the latest edition of the ADB's Asian Development Outlook Update, the World Bank's South Asia Economic Focus, and the IMF's World Economic Outlook —all published in the last few weeks —to see the uncertain outlook.

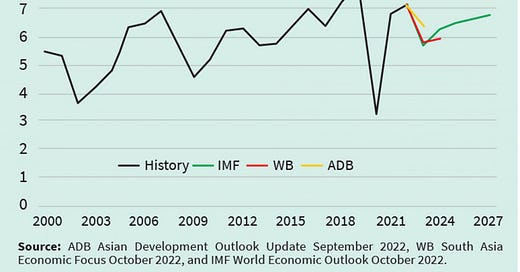

All three agencies expect real GDP growth to slow in 2022-23 fiscal year (Chart 1). As used to be the case, the ADB is more optimistic than the Washington-based institutions. The IMF projects the economy to recover gradually to grow by 7 percent a year by 2027.

All forecasts and projections are, of course, uncertain for the simple reason that we cannot see the future. Why are these forecasts more uncertain than usual?

There are two reasons to be cautious about these projections. First is the usual quibbles about the credibility of the official data that form the basis of these assessments. Did the economy really grow by over 7 percent last year? Is a 6 percent growth really credible this year?

There is now strong evidence that Bangladeshi authorities fudge national accounts statistics. As recently reported by the Economist, for example, Bangladesh is among the worst offenders among 'partly free' countries when it comes to overestimating economic growth.

Of course, the international agencies are stuck with using the official data, although they can, and do, adjust these as much as possible in their analysis. More importantly, criticism of any analysis based on the official figures, valid as they may be, can only take one so far. If one were to stop using the official data altogether, then no serious analysis would be possible, and one would be left to just their opinions and biases.

Leaving aside the complaints about the data, let's turn to the second, and more serious, reason to be cautious about these growth forecasts —when considered alongside the forecasts for other economic indicators, the outlook appears far more uncertain than is usual.

That is, let's not focus on the 6-7 percent numbers as such, and accept the central growth narrative presented in Chart 1 of 'a modest slowdown this year and a gradual recovery in the medium term'. When one looks at the inflation, current account, and fiscal projections from these agencies, one cannot at all be confident about this growth narrative.

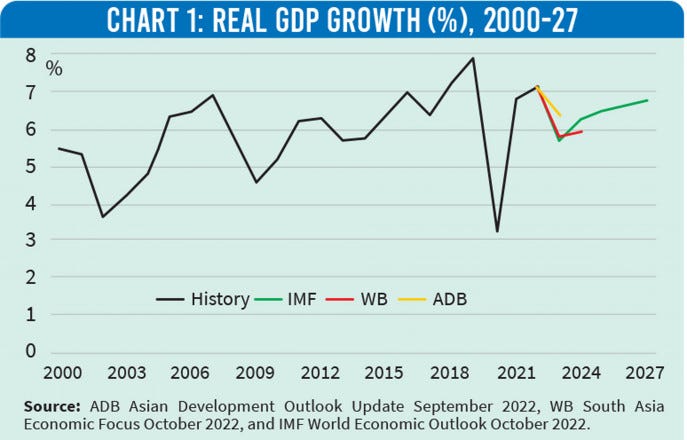

Let's start with inflation. Everyone expects inflation to be higher this year (Chart 2). The ADB figures, released back in September, are woefully out of date. Are the Washington institutions any better though?

Again, let's not belabour the point about the accuracy of the official statistics. Maybe the inflation is actually far above what the government says. Leaving that aside, let's look at the IMF's forecasts, which have inflation peaking at 9.1 percent in 2022-23 and then eventually ease back to 5-6 percent range.

So, according to the Fund, the Bangladeshi economy is expected to achieve a solid disinflation while maintaining a strong recovery in the coming years. That's certainly a very comforting story. And Bangladesh did, indeed, experience significant disinflation while accelerating growth in the mid-2010s.

But that was then, this is now. Back then, global interest rates and inflation were low. How confident can we be about this narrative against the global backdrop of war, energy and food price shocks, rising dollar and interest rates, and looming debt distress?

Back then, Bangladesh benefitted from strong exports and remittances growth. Perhaps this will be the case this time around too? Or perhaps not. None of the agencies are projecting an export boom, with the IMF forecasts being the most pessimistic of the three. And that's not surprising given the sharp rise in inflation and interest rates in Bangladesh's exports markets.

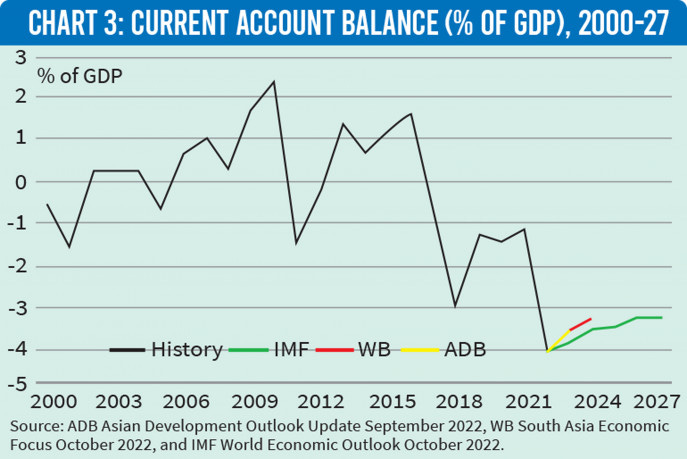

The World Bank and the ADB are more upbeat about remittances, citing record numbers of Bangladeshis going abroad, and strong labour market in the destination countries. They also expect strengthening remittances to help narrow the current account deficit into the medium term (though their published forecast horizon is not that long). In contrast, the IMF projects the current account to be in deficit of over 3 percent of GDP even in 2027 (Chart 3).

Let's unpack the Chart 3 above. Bangladesh used to run a moderate current account surplus or deficit. This changed towards the end of the 2010s, before the pandemic, when the current account started to be in deficit more regularly. Of course, in 2021-22 the current account deficit widened sharply, reflecting strong rise in imports, particularly (though not exclusively) of intermediate goods. While one might expect some of the unusual developments of 2021-22 to unwind, it is clear that the Fund now considers Bangladesh to be a country that runs a persistent current account deficit.

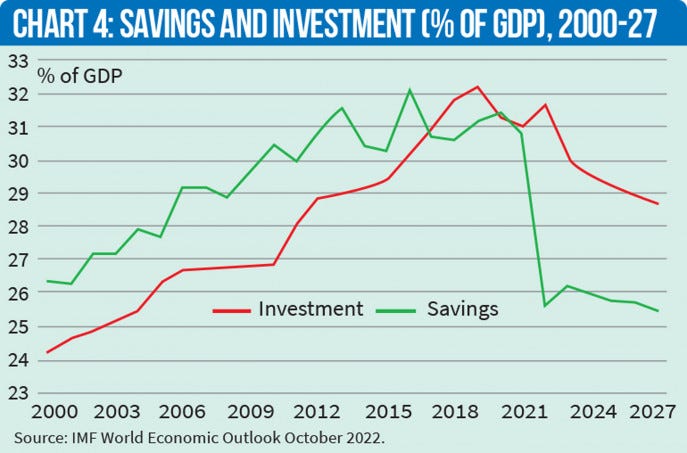

Of course, the current account is also the difference between how much a country saves and how much it invests. A country running a current account deficit is one where its domestic savings are not large enough to finance its investments, the difference being sourced from abroad. Chart 4 shows that the persistent current account deficit that the Fund is projecting reflects lower domestic savings rather than a pick-up of investment. Indeed, investment is projected to decline as a share of GDP, but is still expected to remain higher than savings.

Okay, so the Fund's narrative now seems to be along the line of 'gradual economic recovery supported by a drawdown in savings while the economy disinflates'. Again, how confident can we be about this story?

Chart 4 shows around 5 percent of GDP drop in savings. Chart 5 shows that the government's budget deficit has widened in 2021-22, but only by around 1.5 percent of GDP. That is, the current account deficit projection does not appear to be primarily a public sector story.

That said, Chart 5 also shows that the budget deficit had been gradually worsening even before the pandemic. Bangladesh used to run a budget deficit of 3 percent of GDP. Now we are looking at budget deficits of 5 percent of GDP. Can the additional deficit of 2 percent of GDP a year be financed for so long?

Underpinning the Fund's forecast is a gradual, 2 percent a year, depreciation of the taka. That is, the Fund does not see much difficulty in financing either the budget or the current account deficit. Their view is summed up thus in the Asia-Pacific Regional Economic Outlook:

In Bangladesh, the war in Ukraine and high commodity prices has dampened a robust recovery from the pandemic. The authorities have preemptively requested an IMF-supported program that will bolster the external position, and access to the IMF's new Resilience and Sustainability Trust to meet their large climate financing need, both of which will strengthen their ability to deal with future shocks.

Economic prognosticators always caveat their crystal ball gazing with nods to uncertainty. But this story of 'recovery, disinflation, and deficits without any financing problems' seems to be highly uncertain to say the least!

First published in the Business Standard.

Further reading

Why I worry about inflation, interest rates, and unemployment

Olivier Blanchar, 14 March 2022

Food insecurity is a bigger problem than energy

Targeted cash and expertise are needed in the worst-hit areas, rather than sending food stocks

Megan Greene, 17 May 2022

Inflation and unemployment. Where is the US economy heading over the next six months?

Olivier Blanchard, 8 Aug 2022

Hot milk: what rising prices tell us about inflation

If the cost of a basic commodity is surging in a competitive market then pressures may persist longer than some expect

Claire Jones, 20 Aug 2022

Bangladesh is being ‘killed by economic conditions elsewhere in the world’

Power blackouts and high import prices are fuelling fears that the country’s previous gains could be reversed by the global crisis

Benjamin Parkin and John Reed, 24 Aug 2022

Agustín Carstens: ‘It’s very important central banks let people know what is happening’

The Bank for International Settlements chief warns that persistent price rises and tightening labour markets will fuel high inflation

Chris Giles 25 Aug 2022

Understanding Recent US Inflation

Although US monetary policy was too aggressive for too long, the likely culprit behind the recent surge in consumer prices was an extraordinarily expansionary fiscal policy

Robert Barro, 30 Aug 2022

Private credit is growing in times of high inflation. What does it mean for the economy?

Reasons behind the rise of private credit, what it means for an economy under inflationary pressure and how to curb this growth.

Nasif Tanjim, 31 Aug 2022

Debt-Stricken Sri Lanka Reaches Initial Deal for I.M.F. Bailout

The package includes nearly $3 billion in loans for an island nation that ousted its president amid a devastating economic crisis.

Skandha Gunasekara and Mujib Mashal Sep 1, 2022

Every fresh lurch upwards prompts some big questions

The Economist, 8 Sep 2022

How Food and Energy are Driving the Global Inflation Surge

Rapid increases in food prices have been one of the main drivers of quickening inflation around the world

Phillip Barret, 12 Sep 2022

Addressing the Fiscal Conundrum in Bangladesh

A core policy reform is tax revenue mobilization, which has turned out to be the Achilles Heel of Bangladesh development strategy.

Sadiq Ahmed, 18 Sep 2022

Indonesia’s unexpected success story

The economy is prospering despite the sense of crisis elsewhere but the country’s politics could become more unstable

Mercedes Ruehl and Joe Leahy 20 Sep 2022

A global manufacturing slowdown suggests worse is to come

Recession would be brutal for countries that have still not recovered from covid-19

The Economist, 21 Sep 2022

The Unexpected Rise in Remittances to Central America and Mexico During the Pandemic

Remittances hit record levels in 2021 driven by rising US wages and unemployment insurance relief

Yorbol Yakshilikov 21 Sep 2022

The Bank of England does not have a lot of options

Robin Wigglesworth 22 Sep 2022

Adam Tooze, 22 Sep 2022

Bangladesh external debt situation and vulnerabilities

Sadiq Ahmed, 25 Sep 2022

Finance prepares to-do list to offset effects of global slowdown

Abul Kashem, 27 Sep 2022

The financial tide is going out as a rising US currency has recessionary effects elsewhere

Martin Wolf, 28 Sep 2022

Economists now accept exchange-rate intervention can work

The Economist, 29 Sep 2022

The Stagflationary Debt Crisis Is Here

The Great Moderation has given way to the Great Stagflation, which will be characterized by instability and a confluence of slow-motion negative supply shocks.

Nouriel Roubini, 3 Oct 2022

The inflation problem will get better before it gets worse

When current disruptions recede, the underlying rate of inflation will remain higher than before the pandemic

Henry Curr, 5 Oct 2022

Lending rate cap to be lifted soon: BB tells IMF

Sakhawat Prince, 27 Oct 2022