If we win here we will win everywhere. The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I hate very much to leave it. And you had a lot of luck, he told himself, to have had such a good life. … You do not want to complain when you have been so lucky…

Robert Jordan, an American volunteer fighting against the Fascists in the Spanish Civil War, thinks to himself as he awaits, wounded, to ambush an enemy cavalry before he dies, so that his comrades can escape.

That’s the climax of the classic Hemingway novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. Over five hundred pages describing only four days, the novel narrates Jordan’s mission — to blow up a bridge with the help of a local guerrila band, his liaison with Maria — a survivor of Fascist brutality, and the moral dilemmas of war and justice — even the ‘good guys’ end up doing things that might be not-so-good.

How is it that Steven Spielberg or Clint Eastwood hasn’t made a movie of this?

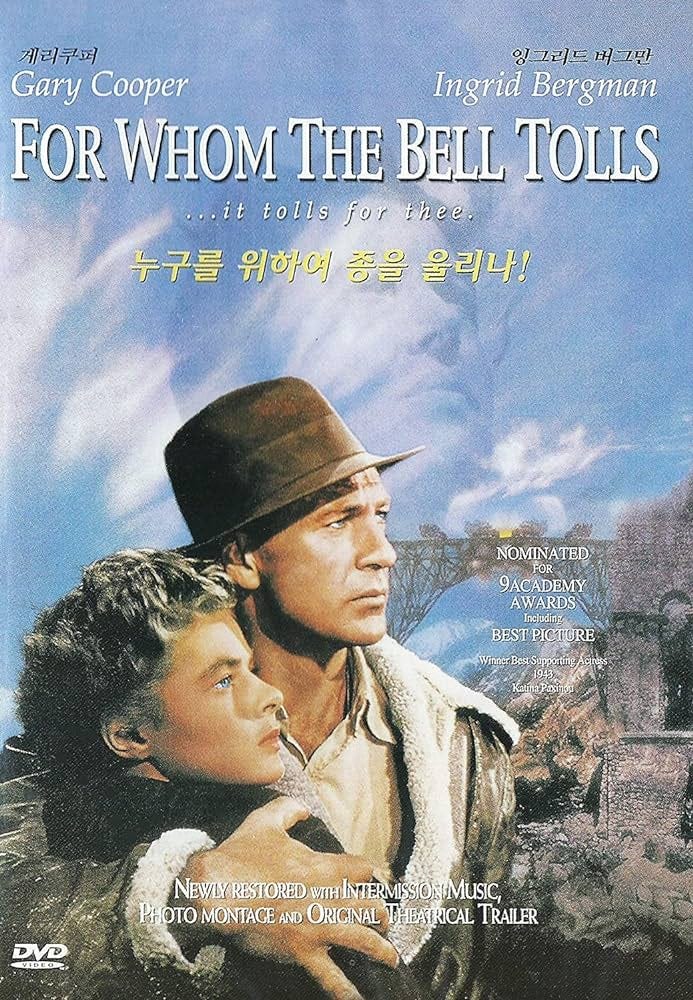

There was a film adaptation in 1943, starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman. It was nominated for Oscar, which that year went to the far more famous Bergman-starrer.

Humphrey Bogart’s Rick Blaine was once an idealistic American helping the good guys in Ethiopia and Spain — one can even imagine a pastiche prequel where he and Jordan were together in Madrid. But by the time we meet him in that gin join in Casablanca, Rick, we are told, ‘sticks his neck out for nobody’, until, of course, she walks in, with her husband, and Nazis in pursuit. A love triangle melodrama. An allegory of American isolationism. One of the greatest movies of all time. Casablanca is all of that and more!

Hemingway’s novel is named after a 17th century English poem:

No man is an Island, intire of it selfe; every man is a piece of the Continent, a part of the maine …. any mans death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee.

By the end of the movie, Rick rediscovers the sentiment and returns to the good fight.

In hindsight, Fascists in general and the Nazis in particular are clearly bad. But this was not at the time. Many in the liberal democracies of the global north as well as among the freedom fighters of the global south admired them. And it wasn’t just Charles Lindbergh and Subhas Chandra Bose. Mohandas Gandhi called Mussolini ‘one of the gratest statesmen of the time’, echoing Winston Churchill’s accolade for the dictator — ‘the Roman genius’ and ‘the greatest law-giver among living men’. The line between good and bad can be pretty blurry indeed!

But there clearly are lines. And when those lines are crossed, one must act otherwise the world stops being a fine place, perhaps not for oneself directly and immediately, but eventually and permanently.

It is hard to escape the feeling that many such lines have been crossed as we say good bye to 2023.

But the sacrifices of Jordan and Blaine remind us that it is never too late.

The world indeed is a fine place, very much worth fighting for.

The fight, of course, does not need to involve violence. In fact, most fights, struggles, jihad in its original meaning of the word before it got vulgarised by lunatics, are not violent. Nor are all struggles for liberal democracy, freedom of speech and other grand ideas. Problems of the human heart in conflict with itself, to paraphrase William Faulkner, can and do change how feel about the world!

One of the most evocative songs of 1971 talks of saving a flower, or a smiling face, as the reasons for fighting — they, after all, are what make the world a fine place. And one can save a flower, and ensure a smiling face, by watering a garden regularly. Small acts of kindness and thoughtfulness are no less important a part of the struggle, even if we have reached the stage where, to echo Omar Khayyam by way of Edward FitzGerald, we have to shatter to bits the ‘sorry Scheme of Things entire’ before reshaping ‘it nearer to the Heart's Desire’.

Small or big, internal to our own hearts and minds or global issues, one cannot wish away problems and do nothing, because bad stuff will happen if good people do nothing.

Further reading (and music)

Casablanca as Plato’s Symposium (Srsly!)

Nicholas Gruen, 22 February 2023

Flamboyant pessimism serves no useful purpose

Noah Smith, 22 February 2023

Fearmongering about people fleeing disasters is a dangerous and faulty narrative

Yvonne Su and Corey Robinson, 12 March 2023

Life under the rule of the Taliban 2.0

For half of Afghans the mullahs’ regime is less bad than feared

The Economist, 1 May 2023

A migrant kind of love: Inside the long-distance relationships of Bangladesh's migrant workers

Kamrun Naher and Masum Billah, 15 May 2023

Lancet Obituary

Andrew Green, 20 May 2023

Demand for chocolate causes more illegal deforestation than people realise

New maps show the extent of the destruction in big cocoa-producing countries

The Economist, 2 June 2023

Dystopia and the mainstreaming of anti-Asian racism, part 3

Paranoid tales about a Japanese fifth column contributed to an atmosphere of racial fear and hate that culminated in a national tragedy

JM Berger, 2 June 2023

Dawn to Dusk on the Corner Where Bangladeshi Brooklyn Gathers

In “Little Bangladesh,” a growing community embraces tradition, and adapts to new trends.

Jonah Markowitz, Karen Zraick and Samira Asma-Sadeque, 13 June 2023

Alice Evans, 3 October 2023

Can you write up a piece evaluating the manifesto for the BNP party? Currently everyone is just fueled by anti establishment politics.