Many years ago, Bill Clinton described the fundamental American political fault line as one being an argument over the 1960s — those who thought the sociocultural changes of that decade were a net positive were Democrats. When I started following Bangladesh politics, about a quarter century ago, I thought the similar fault line for us was 1975 — if you thought Bangladesh took a turn for the worse as that pivotal year ended, by the late 1990s you were probably an Awami League supporter.

This schema was already out of date by the time I started writing regularly and seriously, during the 1/11 regime. By then, 1975 was a distant memory for most. At that time, many speculated India and Islam might be the things future politics would revolve around, and I didn’t differ.

Zafar Sobhan had a particular take on it that I liked (sadly I have lost the link to the article whence he proposed it). Writing well before the culture wars of 2013, he noted that political fault lines in Bangladesh remained around sociocultural norms and markers — identity being one way to describe it. Those subscribing to a Bengali identity, as demonstrated through an affinity for Tagore for example, were likely to gravitate towards Awami League. Those subscribing to more Islamic norms might gravitate to Jamaat and other Islamist parties. And those favoring a westernised synthesis of both found themselves in the BNP.

Well, the Hasina despotism made all that redundant. And the Long July has made Hasina a non-factor in future politics — whatever one might privately believe, it is hard to see a serious political force in Bangladesh that champions the Hasina regime.

What then are the political fault lines in today’s Bangladesh? Where might the key players sit? And how might things evolve?

Nayel Rahman did a facebook post soon after Hasina fled that I found to be very astute, and I build on it below.

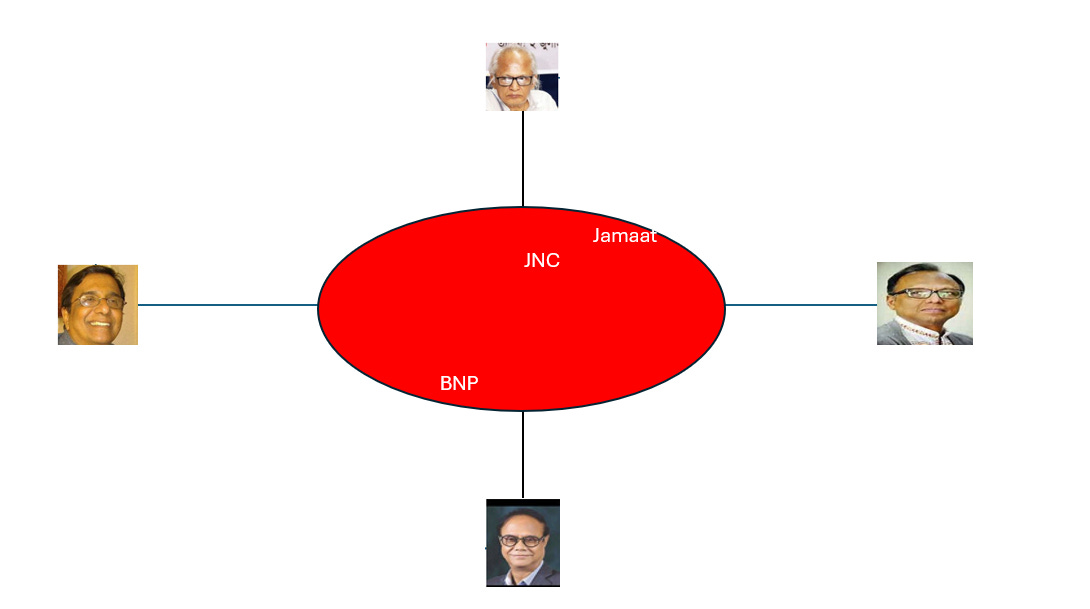

Imagine a 2-axis, four quadrant diagram.

On the horizontal axis, we have the old Muslim vs Bengali, Shapla vs Shahbag cultural identities, with one change — the Bengali-Shahbag cultural politics is shorn of any fealty to the cult of Mujib. If you are excited by the prospect of 100 cows being slaughtered at Ramna on 14 April, you are on the Mahmudur Rahman side of the axis, while if you are mortified by it then Matiur Rahman is your man.

Of course, the cow slaughter parties are just one manifestation of the cultural cleavage, we can talk about gender, minority communities, heterodox lifestyle and all sorts of things here, recognising fully that this simplified schema misses multitude of complexities that make up each one of us. Still, I think the simple schema does a good approximation of today’s Bangladesh.

In addition to this horizontal axis of identity politics / culture wars, there is also a vertical axis based on how we want to rebuild the country that has been gutted by Hasina. Economic policy is part of this, but it is more than just the economy, and covers the entire approach of organising the polity. On one side of this axis we have Farhad Mazhar, symbolising those who think a radical revolutionary reconstruction of the republic is necessary. On the other side we have Ahsan Mansur, symbolising conservative technocracy.

Again, a lot of nuance is missed in the simple framework. For example, there is no uniform way of revolution, just as there is no standard technocratic conservatism. But again, the simple axis does a good approximation of the divide.

So, we have a diagram such as the following.

What is the red circle in the middle? It is, by construction, where the majority of Bangladeshi voters are. It is the politics of synthesis that Ziaur Rahman tried to build. It is what Faruk Wasif calls the Bangladeshponthi politics.

Electoral politics is the process through which parties try to find the median voter. As things stand in 2025, the stylised depiction of Bangladesh politics is that BNP is approaching this middle from the southwest quadrant, encompassing the Matiur-Mansur side of things and while not giving up ground on its share of Mazhar-Mahmudur crowd. In contrast, Jamaat and perhaps Jatiya Nagarik Committee (or whatever the new party calls itself) is approaching it from the northeast quadrant.

Various social media firebrands are clearly on the northeast quadrant of this schema. If BNP wins a brute majority in the election, and JNC fails to transform into a credible opposition, our politics could well gravitate towards a fight between flailing center and a radical northeast (or a rightist alliance if you like). Alternatively, we could see a BNP-JNC two-party politics inside the red circle.

I plan to write more about the above over time.

Meanwhile, what about the unrepentant Mujibists, you ask? Well, what about them?

Further reading

Dispatch from Dhaka: Government’s shifting narratives amidst a sea of red

Shahidul Alam, 5 Aug 2024

Zafar Sobhan, 20 Sep 2024

তারেক রহমানের এই দৃষ্টিভঙ্গি কি বিএনপির ‘ঘরে’ ফেরার লক্ষণ

সাইমুম পারভেজ, 14 Nov 2024

Inside Bangladesh’s Media Blackout and How Its Effects Linger

Cyrus Naji, 29 Nov 2024

Rebuilding national unity in post-Awami-fascist Bangladesh is a massive uphill task

Rezaul Karim Rony, 31 Jan 2025

Recommendations of Bangladesh’s Constitutional Reform Commission

Ali Riaz interviewed, 3 Feb 2025

Balancing Bangladesh’s ‘imposed history’

M Adil Khan, 5 Feb 2025

The practical path to dissolving a “fascist” party like Awami League

Md Ashraf Aziz Ishrak Fahim, 5 Feb 2025

Could the Attack on Mujibur Rahman's Home Dhanmondi 32 Be a Turning Point for Bangladesh Politics?

Arka Deb, 7 Feb 2025

How Bangladesh’s public administration fails its people

Subail Bin Alam, 8 Feb 2025

নাহিদ ইসলাম interviewed, 8 Feb 2025

এরদোগানের একে পার্টিসহ তিন দেশের চার দলের আদলে নতুন দল করতে চান ছাত্ররা

আনিসুর রহমান, 9 Feb 2025

Fascinating! It would be great if you could include a Bangla version as well. This way, you can connect with a broader audience, including people like me.