Slouching towards democracy

A one-year assessment on the government’s performance would find it has performed adequately, and the country is firmly on the road towards democracy

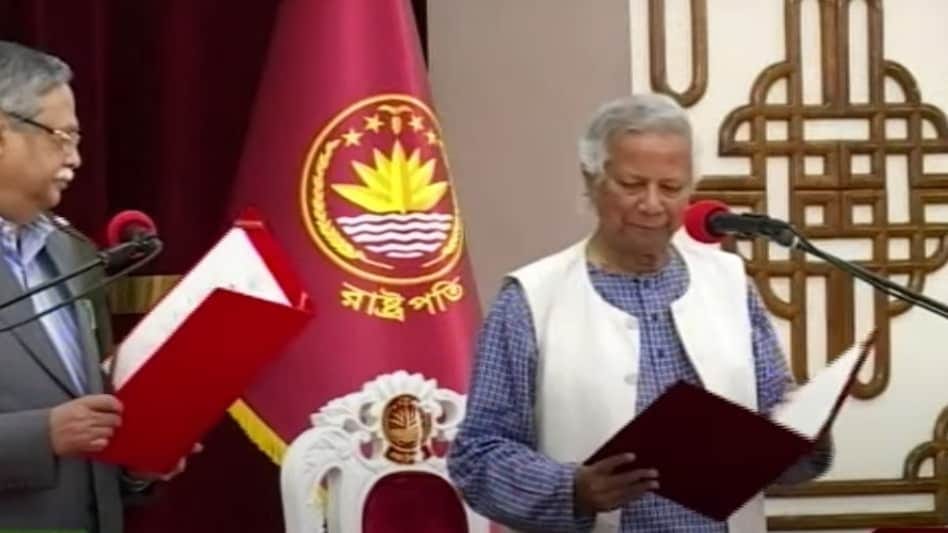

Ending nearly three days of uncertainty after Sheikh Hasina had fled after the Long July, Professor Yunus formed an interim government on August 8, 2024. A one-year assessment on the government’s performance would perhaps find it has performed adequately, and the country is firmly on the road towards democracy.

Of course, any such assessment is inherently subjective. The administration did not -- indeed, could not possibly have -- issue(d) any annual key performance indicator checklist against which we could mark them. However, Prof Yunus himself and several advisors have repeatedly stressed two sets of objectives: first, justice for the July massacre as well as the abuses of the fallen regime; and second, lasting reforms to prevent a return of despotism, accompanied by elections. In addition, there are two implicit objectives: day-to-day running of the state; and managing the political transition from despotism to democracy.

In what follows, I have attempted to assess how the government has been performing against each of these objectives.

Let’s start with the day-to-day functioning of the government.

No one in our history -- including the Mujibnagar cabinet that returned to a war-ravaged country in December 1971 -- had a worse starting point than the current interim government. I have said this many times, but it is worth repeating for it stresses the point: the central bank governor had fled the country after the previous regime fell, the Imam of the national mosque ran away, the police force and civilian law enforcement agency melted away -- such was the magnitude of the collapse.

The Awami League leaders used to say that hundreds of thousands would be killed by their enemies if Hasina were toppled. In similar circumstances in other parts of the world hundreds if not thousands are killed in retribution. Against that, Bangladesh did not in fact descend into anarchy. Not even in the fateful first few days after the collapse of the Hasina regime when the country didn’t even have a government, much less a police force.

One year on, arguably the single biggest failure of the interim government is in the realm of law and order. The biggest testament to this failure is the presence of defence forces on law enforcement duties with magistracy power for over 10 months now.

Could things have been better? Could the police forces have been thoroughly restructured? After a similar popular uprising in Georgia over two decades ago, the entire police force of the country had been fired overnight, and a new force was successfully raised.

In contrast, members of the dissolved Baathist security forces formed armed militia to fight American occupiers and Shia factions in Iraq after the ouster of Saddam Hussein regime.

That is, the international experience suggests reforming security forces and establishing law and order in a post-uprising situation is, to put it mildly, risky. The interim government may not have done a good job, but let’s also acknowledge that the job was difficult.

The interim government’s bigger failure, arguably, has been on the political front against the backdrop of the law and order vacuum -- let me return to this later.

Hasina also left behind an economic mess. An average person does not care about the intricacies of macroeconomic management. They see high prices and stagnating income -- and it’s not a solace to them that these are Hasina’s fault and it will take a long time for things to turn around.

Nonetheless, the government’s performance on the economy has been particularly strong. A full-blown banking collapse has been avoided -- a major success. Taka has been stable against the dollar, and inflation has moderated. If the task was to stabilize the economy, the interim government’s performance has been well more than adequate.

Finally, the government has been successful in resetting relationships with the world. There has been tremendous goodwill towards Bangladesh from all governments, except of course that of India. The Trump administration has not treated Bangladesh any worse than our main economic competitors, a genuine worry given Professor Yunus’s close personal connection with the US Democratic Party. Various Eurasian powers have approached Dhaka with positive entreaties. Even in New Delhi, the message has been sinking in that the Hasina regime days will never return, and a recalibration is necessary.

Yes, there are rooms to improve on each of these areas, and the ones not mentioned. But overall, the interim government has performed creditably as far as the day-to-day management of the state is concerned.

It is harder to judge the next objective, that of justice, which involves three elements: rehabilitation of victims and their families; trial of Hasina as well as her top cronies and minions; and reconciliation and healing.

While members of the government have claimed that rehabilitation of the victims and their families -- treatment of the injured, support for the martyrs’ families and so on -- is its top priority, has the performance been adequate?

There are visible signs of progress on the trial front. The United Nations has been involved in assessing the magnitude of the July massacre and aftermath. A trial process has been progressing. Commissions have been working to unearth abuses such as illegal abduction. Against that, there are phony charges brought by local opportunists, and the government has utterly failed to manage such shenanigans.

One hopes that the long arm of the law will get Hasina from her safehouse in New Delhi, not to mention her cronies and minions. One can also be cynical and note that most fallen despots never face justice. I tend to be in the latter category and have little expectation that we will get to hold Hasina and her thugs to account for their crimes. And without justice, how can there be reconciliation?

But this is for the future. For now, the government has performed on the trial front.

Overall then, on the justice objective, the government is performing, though can arguably do much better.

Moving on to the next objective -- that of reforms and restoration of democracy -- the picture is clearer, and the verdict is that the government has performed quite well, and we will soon see the results.

The government announced a reform roadmap last autumn, and has adhered to it. Commissions had been set up to explore the constitution, the election process, corruption, public administration, the police, the judiciary, health system, labour, gender, and the environment. The recommendations were taken to all democratic political parties. The result is being collated into the July Charter that all parties are expected to sign, pledging implementation of agreed upon reform measures within two years.

Will these reforms turn Bangladesh into a Scandinavian state? Hardly. Could a more radical reform package have been envisaged? Sure. However, the measures that have been agreed upon are the ones that are within the constraints imposed by our political reality. The package that has been agreed upon, if implemented, will improve governance and politics. That is progress that should be acknowledged and welcomed.

The Chief Advisor has announced that the election will be held before next Ramadan. That too is very welcome.

But the road to the elections has been made much rougher than it needed to be because of the government’s lack of competence at political management.

The caretaker governments of 1991, 1996 and 2001 were non-partisan and apolitical -- each had one specific task, hold a free and fair election within 90 days. All the political questions about who would form the government after the election and what they would do -- these were not the caretakers’ concerns. The ‘army-backed caretaker government’ installed after the January 2007 coup -- the so-called 1/11 regime -- was in a manner of speaking non-partisan but was openly involved in political games -- the so-called Minus-2 attempts.

The current government has styled itself as interim from the first day. However, Yunus and his advisors repeatedly said they have been put to power by the students and people who toppled the Hasina despotism. That is, this has always been a political government.

Since the government is inherently political, and it derives its legitimacy from those it governs, it has to respond to the citizens’ concerns. And currently the only mechanism for the government to even hear the concerns is protests -- online or on the streets. This is a volatile, combustible state of affairs at best. And the law and order vacuum makes it a very bad state of affairs.

The situation has been worsened by the government’s opaque relationship with its political ‘appointors’ -- the self-styled organizers of the July uprising that eventually formed itself into the National Citizens Party. Any reasonable observer would acknowledge that the members of the interim government, starting from the Chief Advisor himself, appear to have a soft corner for the NCP. What about other political parties, the civil-military bureaucracy that forms the bastions of power in our country, and various activists and civil society platforms with their own agendas and programs to push?

Each of these actors have tried to push what they perceive to be in their best interests. For example, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party wants an election at the soonest, whereas the Jamaat-e-Islami seems more interested in rewriting history. Various online and offline influencers and civil society actors have also tried to push their respective barrows. For many of these actors, a delayed election is better because they might lose their influence under an elected government.

The interim government had initially mismanaged the politics of transition, for example when it comes to mobs associated with religious extremists, pressure groups associated with the NCP and Jamaat, or patronage networks associated with the BNP as well as NCP. Indeed, one might have assessed the government as a failure in politics. The Chief Advisor's characterization of major reforms meant that there was no reason to extend the election date to June 2026. There was nothing in the entire reform package that couldn’t be done by December and another six months would not have made a difference. The needless alienation of the military top brass was another misstep of the government’s own doing.

Fortunately, the interim government has one redeeming quality that stops it from being a political failure. This is a government that listens and thus course-corrects. That’s why it is off to the hustings for the politicians.

First published in the Counterpoint.

Further reading

Bangladesh has a 'very tough job' ahead

Irene Khan, 6 Aug 2024

Revolution to reform: The long and arduous path to lasting democratic change

Sabhanaz Rashid Diya, Shahzeb Mahmood, Rubayat Khan, 8 Aug 2024

One month after the new beginning

Aasha Mehreen Amin, 5 Sep 2024

Two hours with the chief adviser

Mahfuz Anam, 6 Sep 2024

A turning point or a missed opportunity?

Eresh Omar Jamal, 16 Dec 2024

Government must make itself available to questions from the press

Zia Haider Rahman, 19 Dec 2025

Post-uprising Bangladesh poised for next leap: What Feb '26 polls could achieve

Arkamoy Datta Majumdar, 6 Aug 2025