Six months ago today, a brave man stood with his arms wide open, to be shot dead by Hasina’s uniformed goons, changing Bangladesh forever. This week six months ago was marked escalating violence. Last couple of days, meanwhile, have seen Hasina’s niece Tulip Siddiq resign from her ministerial responsibilities in the United Kingdom under corruption charges, while back in Dhaka various reform commissions have submitted their reform proposals.

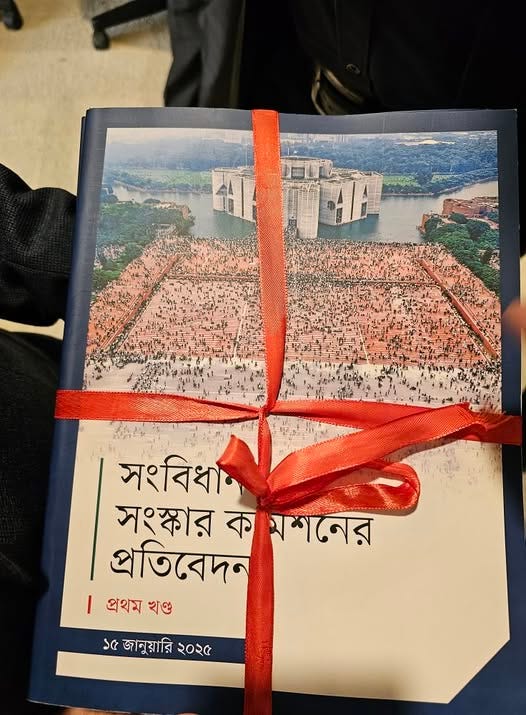

And on personal note, I am about to visit Free Bangladesh. I am also quite chuffed because the key features of Professor Ali Riaz’s Constitution Reform Commission are quite similar to my modest proposals — a proportionally represented upper house to enhance checks and balances between the executive and legislative branches of the government, plus a few other features.

No doubt the details of the proposals — plus those of Badiul Alam Majumdar’s Electoral Reform Commission and Tofail Ahmed’s Local Government Reform Commission, and indeed all the other ones — will be scrutinised carefully. And more importantly, the political parties — particularly the BNP and the yet-to-be formed youth party (I will simply use Jatiya Nagarik Committee, JNC, in what follows) — will need to come to an agreement on the reforms.

This post provides a roadmap through which the constitution can be rewritten and democracy can be restored on a sustained basis. It will require concessions from both BNP and JNC. Concessions that, I am moderately optimistic, will be made for national consensus.

Note that I have used the word rewrite — পুনর্লিখন in Bangla, to use Professor Riaz’s terms —the constitution. While this could mean annulling the existing constitution and frame a whole new document by a new constituent assembly, an amendment by the next elected parliament would suffice. At this point, a historical detour might help.

The process for framing the 1972 constitution is derived from the Mujibnagar Proclamation, which is the foundation of Bangladesh. The Proclamation says that people of the then East Pakistan voted in a free and fair election, but after the Pakistan army refused to hand over power to the people’s representatives and launched a war, people of Bangladesh proclaimed the new country. The proclamation also said that those elected in the 1970 election would form a constitution on the basis of equality, human dignity and social justice.

The 1972 constitution was of course highly problematic for the reasons discussed in the previous pieces on the constitution series. And the constitution was completely rewritten (again, Professor Riaz has used the word পুনর্লিখন publicly to describe this episode) in January 1975 with the 4th Amendment that introduced Bakshal. After 15 August, the Moshtaq regime suspended the Bakshal constitution, declared martial law, and annulled the Bakshal system.

It is interesting that neither the Mushtaq nor the Zia regime annul the constitution. They had precedence — Iskander Mirza annulled Pakistan’s constitution and declared martial law in 1958, and Ayub Khan annulled the 1962 constitution (framed by his own regime) in 1969 and declared martial law. There were also Indian media reports, inaccurate of course, that the Mushtaq regime had proclaimed Bangladesh an Islamic Republic. The reality is, for all the coups and counter coups of 1975, the country remained the same one founded on the basis of the Mujibnagar Proclamation.

Zia consciously did not want to annul the constitution because the constitution was framed with the Mujibnagar Proclamation as its basis. Also noteworthy that Zia did not change the flag or national anthem or the name of the country, despite a lot of pressures. For Zia, these things were all ‘settled’ in 1971 — he said this publicly during the 1978 presidential election campaign.

Instead, Zia introduced a new system — the multiparty presidential system — and new ‘high ideals’ through the 5th Amendment of 1979. This is yet another পুনর্লিখন. Then we had yet another পুনর্লিখন in 1991 when parliamentary system was brought back, reflecting the political consensus between all parties.

Hasina did her পুনর্লিখন in 2011 with the 15th amendment, which the Supreme Court has now annulled. So it is now the constitution as it stood when BNP left power in 2006. As a political party, it is perfectly sensible for BNP to stand by a constitutional set up under which it won two free and fair elections, and formed the largest opposition in the third.

Nevertheless, BNP is amenable to further পুনর্লিখন of the constitution, evinced by its 31 points and its participation in the reform process. But it is important to understand why both for political calculations as well as for historical reasons, BNP is strongly committed to constitutional continuity as much as possible, why it opposes annulling the constitution or even suspending it and replacing it with some Proclamation of Second Republic. Such things historically tend to create grounds for martial law or other undemocratic rule. Constitutional continuity was also why a one-party election in Feb 1996 was necessary — that was the only way to amend the constitution and introduce the caretaker system.

This is why, unless JNC manages to win a landslide electoral mandate, it will have to concede that a second republic is a non-starter. BNP is wary of any such venture, and it is not needed.

This, however, does not mean BNP gets everything it wants. It will likely have to concede that local governments, student council, and professional bodies should be elected before the parliament. More importantly, to the extent that it will be the new parliament that rewrites the constitution through an Amendment Act, BNP (and all other democratic parties) will have to make an explicit promise that they will in fact do this.

Specifically, we can conceive the following set of steps to occur in 2025 and beyond:

Under the guidance of Professors Yunus and Riaz, all democratic parties publicly commit to a National Consensus Compact or Accord — জুলাই 2024 এর অঙ্গীকার —which will not be a legal document but a political one committing to the reform package.

Student council, trade bodies, and local government elections to occur as soon as possible, followed by national election by next winter. That is, the next 12 months will be a carnival of democratic cacophony.

The parliament will be elected on the basis of the current constitution — that is, only 300 seats in the lower house. This parliament will amend the constitution to retrospectively legitimise the Monsoon Revolution and the enact the reforms.

This will be immediately followed by the presidential and upper house elections held under a national government consisting of all parties that have signed the জুলাই অঙ্গীকার.

For the long-term development of viable civilian institutions, the … political leaders of Bangladesh would … have to practise self-restraint, conduct themselves according to the rules framed for political participation and forsake their penchant for “winner takes all” games.

That’s the last sentence of Talukdar Maniruzzaman’s The Bangladesh Revolution and its Aftermath, published when Zia was still alive. These words are still true. Our politicians today, young and old, in JNC and BNP, will do well to heed this. Push for an unnecessary proclamation and there will be louder calls for immediate election. One might win an election, but without commitment to meaningful reforms, the next government will be weak, the country will remain divided, and before long, we will be back to June 2024. And here is a reminder of what that was.

Previous posts on constitution

Further reading

Radwan Mujib Siddiq Bobby and his advisory board

Badrul Alam, Sk Toufiqur Rahman, 27 Aug 2024

Mahfuj Alam on Bangladesh’s Future

5 Nov 2024

City minister Tulip Siddiq named in Bangladesh corruption claim

George Parker, Anna Gross, Chris Kay and Krishn Kaushik, 20 Dec 2024

UK minister’s links to ousted Bangladesh leader under scrutiny after corruption claims

Rafe Uddin, Anna Gross, Krishn Kaushik, 21 Dec 2024

Bangladesh asks India to return ousted leader Sheikh Hasina

Chris Kay and Krishn Kaushik, 24 Dec 2024

The Return of Politics in Bangladesh

Nusrat Sabina Chowdhury, 1 Jan 2025

সাইমুম পারভেজ, 1 Jan 2025

Maayer Daak Included In School Textbook

Mohiuddin Alamgir, 3 Jan 2025

A Year Later: How coercion and horse trading shaped Bangladesh’s controversial January 7 election

Mahtab Uddin Chowdhury, 7 Jan 2025

Dhaka police ‘raided lawyer’s home’ after journalists asked Tulip Siddiq about his plight

David Bergman, Susannah Savage, Rafe Uddin, 8 Jan 2025

Ties between Labour MP Tulip Siddiq and deposed Bangladeshi regime under spotlight

Kiran Stacey, Rowena Mason, Redwan Ahmed, 9 Jan 2025

রিয়াদুল করিম, 14 Jan 2025