(Apologies for double posting - there was a slight error in the previous version).

Macroeconomic policy is like driving a bus. When you are on a bus, you want to get the destination as fast as possible. Similarly, we want the economy to grow as fast as possible. Without growth, there is no job, income, or development. But just the way a bus needs to slow down if on a winding road or a crowded street, macro policymakers need calibrate their policy settings to the economic conditions. Sometimes, this meas slowing the pace of economic growth so that the economy can stabilize.

This had been the case for Bangladesh even before Monsoon Revolution. Like many other countries, Bangladesh faced external shocks in 2022 in the form of Ukraine War and post-pandemic global inflation. However, macroeconomic policy did not recalibrate to stabilize the economy. In fact, policy settings worsened matters. Reserves bled. Taka depreciated. Inflation reached double digits.

Underlying pre-pandemic conditions — megaprojects with not-so-straightforward returns and questionable financing, energy sector and banks laden with problems — further added to the instability.

Then the revolution happened.

So the bus driver now needs to slow down, perhaps reverse gear even in the short term!

What does this mean in practice?

First, the banks.

There are 60 or so banks in Bangladesh. About 10 or so are okay. Another 10 are practically insolvent. The rest also have problems.

If there is one bad bank, a standard policy solution might be to allow it to fail. Most depositors are usually covered by some form of insurance, often publicly guaranteed implicitly or explicitly. So the depositors get their money back, and investors lose out.

But when there are 10 or so bank in that situation, there is a systemic issue. So, what to do?

The central bank and the interim administration has replaced the boards of these problem banks. The next step will be a thorough audit to understand the extent of the ‘hole’. Then will come ‘solutions’. In the meantime, it’s vital that confidence is maintained.

The problem is daunting. However, banking problems are a ‘known known’ — they have happened in many countries over the centuries, and the technocratic solutions are well known. Of course, they require political will. Fortunately, there is no reason to doubt the policymakers’ willingness at the moment.

This is a can that cannot be kicked down the road, and everyone knows it!

Second, inflation.

The good news here is that inflation appears to be easing, though still quite elevated. The Bangladesh Bank governor expects inflation to decline to 7% by winter. The challenge will be to reduce it further to 5%, which may require much tighter policies.

One key challenge here is that Bangladesh Bank and the Ministry of Finance are modernizing their policy framework at a time when both institutions (like every other public institutions) are dealing with severe personnel problems. Recall, the central bank governor and two deputies fled after the revolution!

(Imagine that — a central bank governor fleeing after a political change, that’s how bad cronyism was under the fallen despot!).

Thirdly, the external sector.

On the plus side here, remittances are booming post-revolution. For two years before the revolution, remittances had been sluggish even though people had been leaving the country in record numbers for work, and the recipient countries’ job markets have been red hot. This was because the remitters were expecting a depreciation of taka and relied on informal networks which were buoyed by money siphoned out by the fallen regime’s cronies.

Then came the remittance boycott during the revolution, which appears to have had a material impact!*

If the remittance remains strong, it can create a virtuous cycle of exchange rate stability. Plus, the steady stream of news of financing from multilateral agencies and development partners help.

On the other hand, there is considerable worry on the exports front — I will leave it to others to discuss.

Finally, the pre-revolution outlook was for a current account deficit in the medium term even with the full implementation of the old IMF program. This deficit reflected significant public expenditure which ultimately relied on foreign financing. We didn’t know the rate of return on some of the investment, nor did we know the cost of finance.

That itself was a significant worry. More importantly, external imbalances, bad banks, and authoritarian politics — that’s what made the noxious Monsoon cocktail of the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98!

Well, we didn’t need to experience the cyclone that is a full blown financial crisis to throw out our despot. So we are somewhat ahead of our neighbors of a generation ago. And work by Daren Acemoglu and colleagues suggests that democratic transition can in fact boost growth if the newly democratized governments pursue reformist policies.

On the other hand, work by Dani Rodrik and colleagues suggest that reform is not always automatic or straightforward.

Let’s go back to our bus.

Stabilization means slowing down the bus, or even reversing it somewhat, because we are in a bumpy road. But ultimately, we may need to fix the bus — change engine oil or wheel alignment — before we can speed up. That takes us to the realm of micro issues that my colleagues will talk about.

I think I covered most of the points, but it’s a good idea to write these things down, if nothing else than for archival purposes. There were a few questions.

Institutions, purges, reconciliation

In light of severe personnel problems in key institutions, we have to reconcile with many that served the previous regime. Our problem is aggravated by the fact that many who served the old order are not just of a different political or ideological persuasion, but also are severely ethically challenged and are frankly incompetent. This makes reconciliation, as worthwhile as that is, not very useful for economic governance.

Headwinds before Ukraine: covered above

Banks: covered above (I think I said something more forceful, but sadly didn’t write down what I said)

Corruption / data integrity / transparency

Problems are noted, and some of the issues were covered by other panellists.

New IMF program

The interim administration has requested resetting the IMF program with additional, front-loaded financing. I understand this will be negotiated in the coming months. It’s a good idea. Watch this space.

I am thankful to Prof Mushfiq Mobarak for organizing the event. I understand I missed out on many stimulating conversations.

*Source: EDGE Research & Consulting Limited using Bangladesh Bank data.

Further reading

Corruption and development: Not what you think?

Chris Blattman, 5 Nov 2012

Does corruption harm economic growth?

Tyler Cowen, 19 Nov 2012

Gary Winslett, 1 Mar 2022

বড়রা লুট করলেও কৃষকরা ফেরত দিচ্ছেন

হাছান আদনান, 19 Sep 2023

How Reform Can Aid Growth and Green Transition in Developing Economies

Christian Ebeke, Florence Jaumotte

September 25, 2023

Support for democracy and the future of democratic institutions

Daron Acemoglu, Nicolas Ajzenman, Cevat Girau Aksoy, Martin Fiszbein, Carlos Molina, 19 Dec 2023

Why is Bangladesh so weak at fighting corruption?

Shadique Mahbub Islam, 23 Jan 2024

Emerging Markets Navigate Global Interest Rate Volatility

Tobias Adrian, Fabio Natalucci, Jason Wu, January 31, 2024

১৩ বছরে ভারতের ঋণের মাত্র দেড় বিলিয়ন ডলার ব্যবহার!

ইসমাইল আলী, 4 Feb 2024

পাওয়ার হাউস ভাঙতে আগে অর্থনীতি ধরুন, রাজনীতি পরে হোক

ফারুক ওয়াসিফ, 22 Aug 2024

$450m reserve drop on 11 Aug: Cover-up for Islami Bank misconduct?

Majumder Babu, 3 Sep 2024

ACC goes after ministers, MPs while avoiding bureaucrats

Shahadat Hossain, 19 Sep 2024

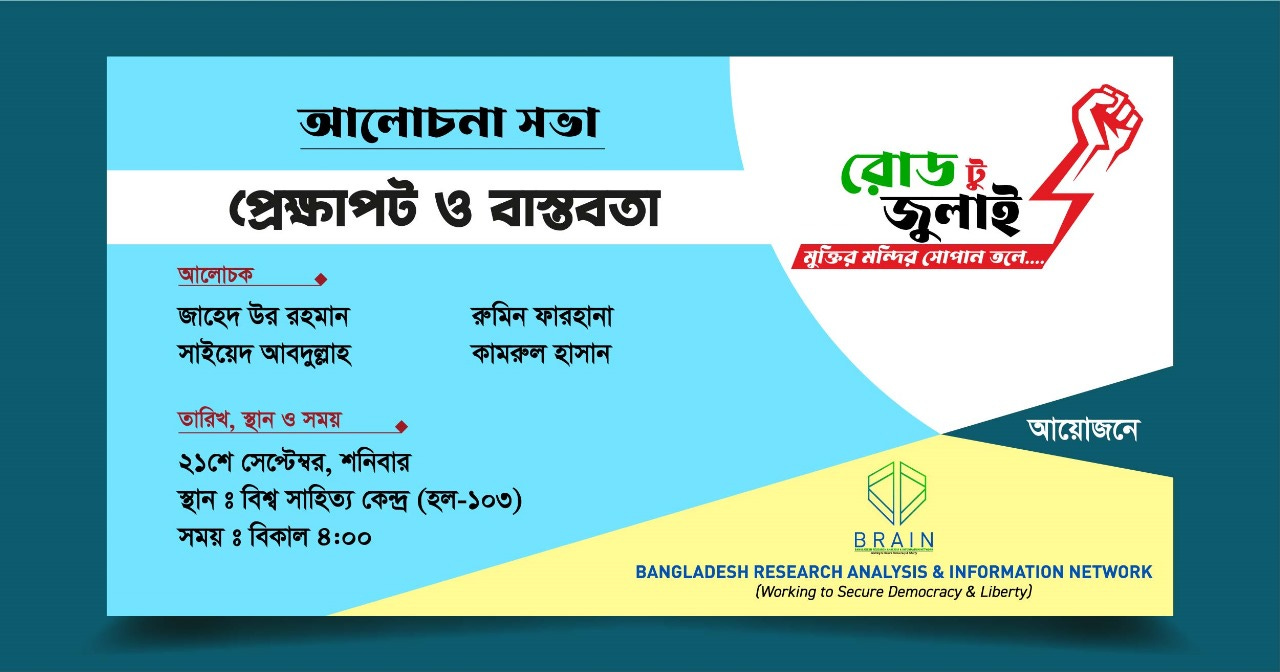

Those in Dhaka, highly recommend the following.

Also, recommend dialing into this.

I'm mostly optimistic about inflation in Bangladesh coming down. Oil prices are down but LNG prices remain elevated because of these damned Europeans. There are also rate cuts in major economies by the end of this year.

But the BB projection of 7-8% by winter seems ridiculous. Last I checked the BB interest rate is still lower than the official inflation rate. Meaning real interest rate is still negative. BB has not been aggressive about increasing interest rate.

On a positive note, the difference between the official exchange rate and the black market rate is less than 1%. This should bring in more remittances (which you mentioned) and export earnings.

Do you think Bangladesh will be able to join ASEAN in the coming years? I'm generally pro India and pro USA but I still think we should have an alliance of medium sized countries in Asia as the world transiions to a multi polar world.