Of the known knowns and unknowns

Risks to Bangladesh economy: exchange and interest rates, banks, pre-election government expenditure, political uncertainty

Donald Rumsfeld, a former American Secretary of Defence, coined the term ‘unknown unknowns’ for the risks that may come about from factors that the decisionmakers might not even be aware of. These unknown unknowns make it difficult to forecast or predict the weather, the World Cup, or the economy.

But when it comes to Bangladesh economy, it is a series of ‘known knowns and unknowns’—factors that are very much known, even if their precise paths and fall outs might not be known, including depreciation of the taka, rise in interest rates, cleaning up of the banks’ balance sheets, pre-election government expenditure, and economic effects of political uncertainty —that will likely make the coming months the most challenging since 1974-75.

The known knowns

But before we get to these known unknowns, let’s consider the known knowns of the economy as 2022 draws to an end. Like many other countries, Bangladesh too has been hit by two related external shocks of rising inflation and a depreciating currency. We know a lot about how these have affected the economy.

The pandemic lockdowns were lifted around the world in an uneven manner, with relative normality resuming in most countries by 2022, but China persisting with a ‘zero covid’ policy. This resulted in a series of supply chain disruptions across many industries, raising prices. These price hikes were initially expected to be transitory. But as inflation continued to surprise on the upside, macroeconomic policy settings started tightening in the advanced economies in general, and the United States in particular. As the US interest rates started rising, the dollar started appreciating against almost all other currencies. The Ukraine War compounded things. Global energy and food prices rose, worsening inflation. The US Fed, and other central bankers, responded by raising interest rate more aggressively. The dollar continued to strengthen.

The taka-dollar rate too was roiled. But instead of allowing a steady depreciation, the government worsened the situation with a mishmash of haphazard measures such as parallel exchange rates, restrictions on foreign exchange transactions, and arrest of foreign exchange dealers on spurious charges. A lack of transparency around the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves put its ability to defend the currency under serious doubt, resulting in a general view that the taka will need to depreciate further against the dollar.

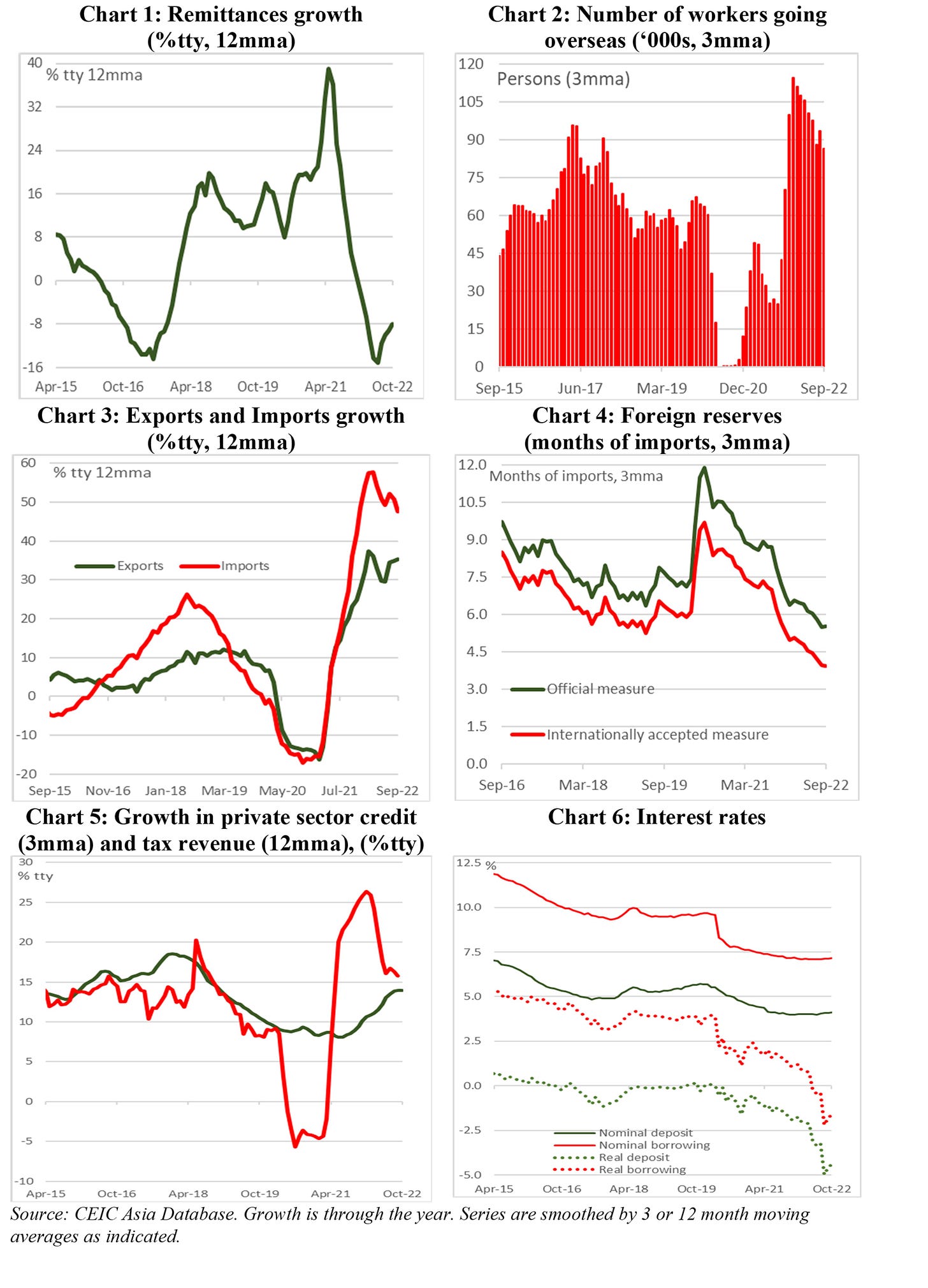

That general expectation is likely plaguing remittances (Chart 1). The number of workers going overseas staged a strong recovery in 2022, with record numbers leaving in the first half of the year (Chart 2). Labour market conditions in the west and the Gulf have been very strong. And yet, remittances remain moribund — remitters may well be expecting taka to depreciate further in the coming months, and therefore holding off their current remittance.

A strong recovery in exports has not been enough to offset the reduction in the supply of dollars because of the weakness in remittance, while an even stronger rebound in imports is raising the demand for dollars (Chart 3). With falling supply of and rising demand for dollars, the central bank has been burning through its reserves (Chart 4) to prevent the taka from sliding even further.

The surge in imports growth reflects, in part, higher global prices of imported energy and intermediate goods, much of the latter relating to the recovery in exports. But strong domestic demand —evidenced by the strength in the growth of tax revenue and credit to private sector (Chart 5)—are also playing a part. With inflation running higher than the capped interest rates on loans, the real cost of borrowing is now negative (Chart 6), which is fuelling domestic demand.

A tricky balancing act

Why have the policymakers not yielded to the expectations and allow the interest and exchange rates to adjust? They might have been, quite rightly, worried about the inflationary effects of a further depreciation of the currency. Further, at least until recently, the strength of the economy was not assured, and perhaps they felt it necessary to persist with low interest rates.

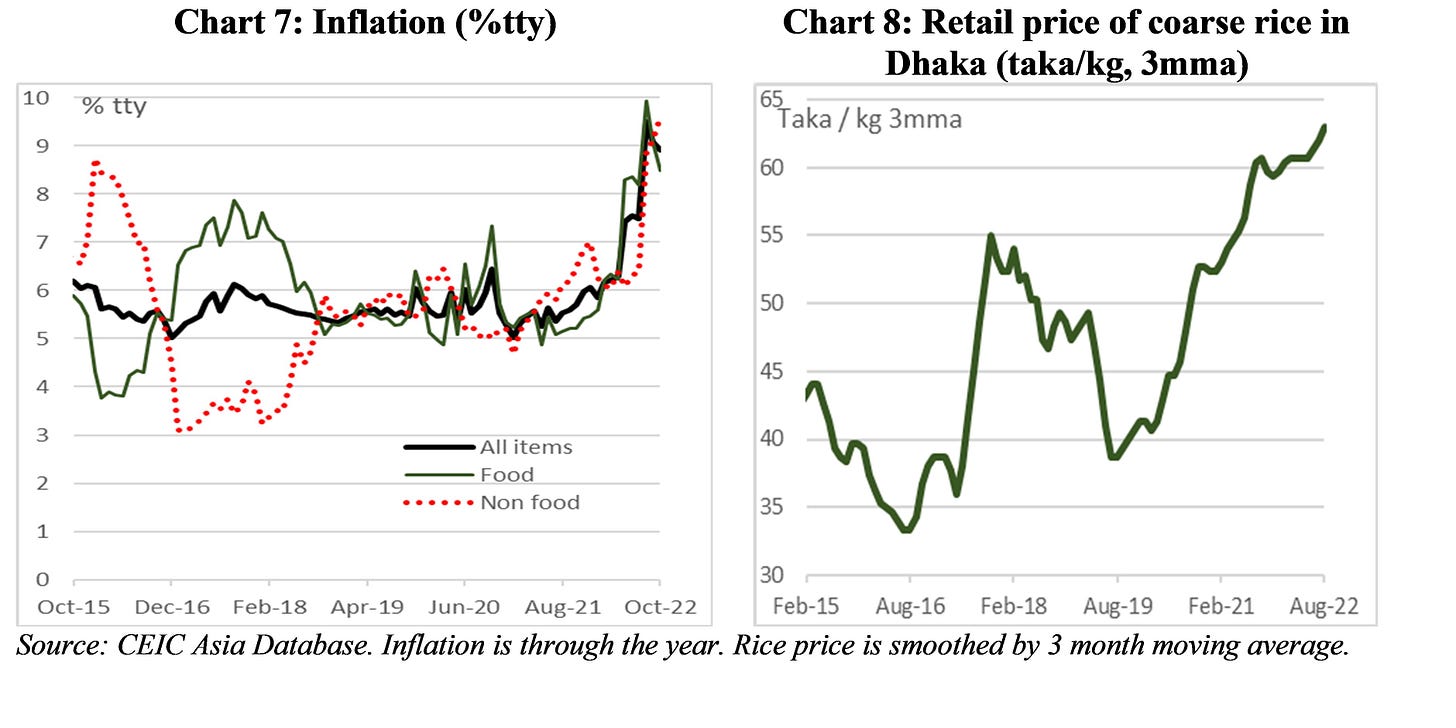

Of course, inflation is continuing unabated (Chart 7), and the price of coarse rice in Dhaka markets has been at record highs for months (Chart 8). That is, the current policy settings are clearly not working. What might happen if the rates were to adjust?

A known unknown is the extent of the depreciation of taka against dollar before the currency stabilizes. Each dollar used to fetch around 86 taka at the beginning of 2022. Will the bottom be at 110 taka per dollar, 120 taka, or 130? While we don’t know the answer to this question, we can make a reasonable stab at the potential consequences.

Firstly, another bout of depreciation will lead to another round of price hikes. Perhaps there might be some respite from inflation with global energy and food prices falling. But a more expensive dollar, and Indian rupee, would mean higher prices for Bangladeshi consumers — there is no getting around to this known known.

Faced with higher prices, however, consumer demand is likely to adjust. Imports growth might dampen as consumers switch to relatively cheaper domestic goods and services. Imports growth would further moderate if interest rates were allowed to rise. Higher interest rates would slow imports growth by acting as a brake on economic growth.

Somewhat offsetting the growth slowdown would be a revival of remittances that would likely accompany a large enough depreciation. Remittances would also help ease the squeeze on household budget, and provide a much-needed relief.

That is, higher interest rates and a cheaper taka would help rebalance the economy from imports to domestic production, but the adjustment path would likely involve higher inflation and slower economic growth. This is a tricky balancing act indeed for the government. But a failure to adjust the interest and exchange rates gradually would risk further depletion of reserves and a sudden adjustment of the rates, with far more severe inflation and slowdown in growth.

So, the known unknown here is the adjustment path the government will choose.

The non-performance anxiety

While inflationary consequences are the reason behind the reluctance to let the exchange rate adjust, this doesn’t explain why the government is keen to keep the interest rates capped in the face of rising inflation. In addition to the stated concerns about the strength of the recovery, the unstated reason might reflect a lack of confidence on the banking sector’s ability to withstand rising interest rates.

Reports galore about the woes in the country’s banks—the scandal involving the S Alam Group and the Islami Bank being the latest in a long series of sordid saga over the past 15 years of malpractices such as the lending of large sums in illicit manner to unscrupulous borrowers.

The banks’ sorry state of affairs has been well known for a long time. Even before the pandemic, the IMF noted in its 2019 Article IV report that “The published NPL ratio likely underestimates potential problems in the banking sector. There has been a growing trend of loan rescheduling and restructuring.”, and warned that the “failure to effectively address the problems in the banking system, including high non-performing loans” posed a “medium” likelihood risk to the economy, and its “expected impact” would be “medium-to-high”, adding “High and increasing non‑performing loans and low capital adequacy would hamper the banking sector’s ability to finance business investment, add fiscal burden, and hamper growth.”

It is a known known that things have only worsened in the intervening years.

The technocratic solutions to these problems are also known knowns. Tightening the criteria for rescheduling or restructuring of loans, strengthening the banks’ corporate governance, enforcing bankruptcy laws and such like, coupled with selected recapitalisation of banks, can de-risk the banking sector without causing a significant hit to the economy. This has been done around the world over the years, with technical assistance from the IMF and other international partners.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that these technocratic solutions require technocrats —regulators and judiciary —to work independently, transparently, and with credibility. Of course, it’s also a known known that technocrats can only work as well as the political realities allow them. Whether the political realities will allow the technocrats to stabilize the banking sector is a big known unknown in 2023.

Meanwhile, the much more frightening and immediate concern might be around the liquidity in one or more of the country’s banks. Hardly a day passes without some ugly news about some bank.

As with the exchange and interest rates, so it is with the banking sector —by delaying the necessary adjustments, the government has increased the probability of a sudden and disruptive one. How this will resolve is also a big known unknown.

It’s the politics, stupid

Of course, the known known political reality of 2023 is that an election is coming, with economic ramifications from what the government might do as well as the actions of the private sector.

Let’s start with the government. In the run up to both 2013-14 and 2018-19 election seasons, government expenditure increased relative to GDP (Chart 9). Expenditure on defence and the general public service —that is, the money spent on the bureaucrats and civil servants across the country —saw strong growth before and after the 2013-14 election, and a massive increase before the 2018‑19 election (Chart 10).

This kind of election year spending is consistent with IMF analysis of 68 developing countries during the period 1990-2010, which finds that in the year of the election, government spending on salaries, subsidies and procurement — the stuff that can help the government get a popularity boost or facilitate patronage— rises by about 0.8 percent of GDP. After the election, however, the time of reckoning arrives, with cuts to public investment and rise in tariffs and import duties. That is, according to the IMF study, not only is the initial expenditure typically wasteful, the way it's eventually paid for is usually harmful to the economy's long-term growth prospects.

Will this pattern play out again in 2023? There is no reason to doubt the government’s desire to go on another spending splurge. Its ability to do so, however, may be constrained by the fiscal squeeze coming from higher interest expenditure (reflecting adjustments to interest and exchange rates) and lower revenue (owing to an economic slowdown).

How might the civil-military officials that the government relies on to run the country respond to a curtailment in their perks and privileges? How might the urban classes react to worsening food inflation and further rise in electricity prices (if subsidies are withdrawn as part of fiscal retrenchment)? Will the streets echo with the sound of marching, charging feet?

These are the known unknowns of the political risks to the economy in 2023.

It is very difficult to say anything definitive about how these political risks might play out. But we can think about a couple of channels through which politics and the economy might interact. Firstly, street agitation, blockade and hartal are designed to disrupt economic activities. We might see a hit to production and trade, flowing on to jobs and income. Secondly, worsening political instability might result in a capital flight, with the affluent classes using illegal and extra-legal mechanisms to transfer their savings abroad.

As it happens, election-related political instability had no discernible effect on industrial production (Chart 11) or foreign reserves (Chart 12) in either 2006-07 or 2013-14. It would appear that on both occasions, the private sector anticipated a political crisis as well as its eventual resolution (whether through a military intervention or a one-sided election or a genuine one), and the economy simply carried on. Of course, in neither of those years was the economy buffeted with exchange rate depreciation, inflation, and banking sector scares.

A steady boat or the 7 Up moment?

There is a very plausible scenario where the economy performs as well as 2013-14 or 2006-07, if not better. Concessional loans from the IMF, multilateral development banks, and development partners should help the economy cope with difficulties wrought on by interest and exchange rate adjustments and the clean up of the banks’ balance sheets. Meanwhile, the global economy might achieve a soft landing, helping with inflation, remittances, and exports. In fact, exports might continue to grow steadily through a global recession because of the so-called Wal Mart effect —whereby western consumers shift towards cheaper clothes that are typically made-in-Bangladesh.

Against that benign outlook is a malignant scenario of a polycrisis perfect storm —a bank run, coupled with rapid depletion of reserves, followed by a collapse in the currency, and inflation nearing triple digits, all the while the finance minister is absent and the prime minister is left at the mercy of economic forces that all her political authority cannot control.

History abounds with examples of catastrophic collapses, when panic and fear grip the decisionmakers, paralysing their ability to act. In the spirit of the World Cup, let us remember the infamous game from eight years ago, when the host and five team winners conceded seven goals in the semi-final.

When it comes to the Bangladeshi economy, will it be a ‘steady boat’ or the ‘7 Up moment’ in 2023? That, dear reader, is the biggest known unknown facing us.

A slightly different version was published in The Business Standard.

Further reading, and watching

Global economy

Christopher Pissarides: ‘Debt and inflation could see us lose control’

The Nobel laureate argues that policymakers cannot tackle social problems by running the economy hot

Delphine Strauss, 14 Jun 2022

Uncoordinated monetary policies risk a historic global slowdown

Maurice Obstfeld, 12 Sep 2022

'We are seeing a perfect storm brewing globally… a slow down is inevitable': Dr Hamid Rashid

Sharier Khan, 18 Oct 2022

Slowing Global Economic Growth is Increasingly Evident, High-Frequency Data Show

While there are multiple headwinds weighing on growth, further policy tightening is expected amid the need to bring down elevated inflation

Tryggvi Gudmundsson, 13 Nov 2022

Why a global recession is inevitable in 2023

The world is reeling from shocks in geopolitics, energy and economics

Zanny Minton Beddoes, 18 Nov 2022

Developing economies

There is a global debt crisis coming – and it won’t stop at Sri Lanka

Foreign capital flees poorer countries at the first sign of instability. The pandemic and Ukraine war ensure there is plenty of that around

Jayati Ghosh, 26 Jul 2022

Against expectations, global food prices have tumbled

Why the war in Ukraine has caused less disruption than feared

Economist, 22 Aug 2022

Yet another inflation problem

Food prices are driving up world hunger.

Siobhan McDonough, 7 Sep 2022

Global Food Crisis Demands Support for People, Open Trade, Bigger Local Harvests

Unprecedented humanitarian challenge requires rapid action to ease suffering of those without enough to eat and provide financing to countries in need

Kristalina Georgieva, Sebastián Sosa, Björn Rother

September 30, 2022

What if emerging markets dodge the default wave?

Ziad Daoud, Ana Galvao, and Scott Johnson, 19 Nov 2022

Staying afloat: Has India weathered the fall of the rupee?

Is the depreciation of the Indian rupee a cause of concern?

Diya Dixit, 24 Nov 2022

Ali Khiziar, 5 Dec 2022

Macroeconomic policy

Stop berating central banks and let them tackle inflation

Despite their slow reaction, now is not the time for a radical redesign of their mandates

Raghuram Rajan, 26 Aug 2022

The United States is fighting inflation with history

Fed chief Jerome Powell wants the world to understand his present decisions are guided by past traumas

Adam Tooze, 28 Aug 2022

Policymakers are likely to jettison their 2% inflation targets

Some by choice, some by accident

Henry Curr, 8 Oct 2022

Fiscal policy can ease the task of monetary policy in reducing inflation while mitigating risks to financial stability

Tobias Adrian & Vitor Gaspar, 21 Nov 2022

The president of the Federal Reserve’s Cleveland Reserve bank on the central bank’s plans to tackle inflation

Colby Smith, 29 Nov 2022

Macroeconomic management in a post-Covid globally uncertain environment

Sadiq Ahmed, 3 Dec 2022

Balance of payments

Exporters in raw material crunch

Jasim Uddin, 14 Sep 2022

Jebun Nesa Alo, 7 Dec 2022

Advanced economies

The UK, not keeping calm and how you can't unburn toast.

Adam Tooze, 27 Sep 2022

The British pound’s recent gyrations point to some basic lessons of currency markets.

Jim O’Neill, 29 Sep 2022

Pandemic-era insouciance seems to be over

Economist, 13 Oct 2022

The economy just doesn’t make sense anymore

How’s the economy doing? Depends where you look. Seriously.

Emily Stewart, 2 Dec 2022

‘Wage inflation? What wage inflation?’ ask workers

Cost of living increases put employees in the red even as the labour market remains tight

Rana Faroohar, 5 Dec 2022

Another week of data with more signs that we are on a path to lower inflation next year

Inflation remains above pre-Covid levels; that is a hardship for families. And we have more reasons to be increasingly, cautiously optimistic about inflation slowing more.

Claudia Sahm, 10 Dec 2022

Finance Minister

আহসান এইচ মনসুর, 27 Oct 2022

অর্থমন্ত্রীর নিষ্ক্রিয়তা নিয়ে প্রশ্ন

অর্থমন্ত্রী আ হ ম মুস্তফা কামাল মন্ত্রণালয়ে নিয়মিত অফিস করেন না, অনেক সভায় থাকছেন না, এমনকি কারও পরামর্শ নিচ্ছেন না।

ফখরুল ইসলাম, 27 Oct 2022

IMF program

Abul Kashem, 9 Nov 2022

Anisur Rahman, 16 Nov 2022

Banks

আমানত-সঞ্চয়ে ঝুঁকির ভয়, নাকি ব্যাংকের ওপর আস্থার সংকট

ফয়েজ আহমদ তৈয়্যব, 21 Nov 2022

কল্লোল মোস্তফা, 2 Dec 2022

Islami Bank’s loan scams were not unknown to policymakers

Says PRI Executive Director Ahsan H Mansur

Golam Mortoza, 6 Dec 2022

ফয়েজ আহমদ তৈয়্যব, 8 Dec 2022

Videos

Everywhere I hear the sound of marching, charging feet

The better Brazil-Germany match