Over the past few weeks, we have been watching a royal funeral and a coronation, and a bubbling cauldron of dynastic intrigue and subterfuge in the race to inherit the throne. Dynasties are for the weird people in a faraway island, or the imaginary world conjured up by George RR Martin -- one might say.

One would be wrong. Dynastic scions and heirs are a common feature in many electoral democracies around the world. Even abstracting from the illustrious members of the family currently ruling Bangladesh and the others that had produced presidents and prime ministers, political families with generations of elected officials and representatives are common across the country.

Why are political dynasties so prevalent?

In a 2016 study of political dynasties of Barisal and Faridpur, Arild Engelson Ruud (University of Oslo) and Mohammad Mozahidul Islam (Jahangirnagar University) hypothesize that political dynasties allow a party to use the heir’s ability to effectively manage networks of political activists, enforcers, businessmen, bureaucrats, and other political players at the local level.

The authors’ basic story can be taken much further.

Let’s start at the micro level.

As the authors argue, politics at the local level depends crucially on successfully managing networks of activists, enforcers, businessmen, bureaucrats, and other stakeholders.

In addition, there are low information voters for whom a candidate’s name recognition is an important factor. These make it a very useful strategy for the political parties to nominate the spouse / offspring / sibling of a famous and popular politician.

What other types of candidates are there?

Parties can nominate celebrities: Movie stars, sportspeople, and so on. They may have the name recognition, though it is hard to see why they would be particularly good at managing local networks.

Who else? The rich come to mind. Successful businessmen can come to the party and buy nominations. And they can then flood the electorate with money, demonstrating their ability to get things done.

There is, however, another type of candidate -- the seasoned, grass-root politician. These are the people who join the party in their youth, at the community or neighbourhood level. They participate in various campaigns and activities, and earn the community’s recognition and trust.

In mature democracies, we can see people like this frequently. They are also more common in countries with well-developed party structures, or where community or “civil society” organizations are robust. In developing countries, cadre-based parties (of left and right) can produce candidates like this. And in both mature as well as emerging democracies, identity politics is conducive to this kind of candidate.

So, to summarize then, parties care about nominating a candidate who can win the election. Their nomination choices are: The scion, the celebrity, the businessman, and the activist.

We can investigate empirically how the major parties nominated their candidates in the four national elections between 1991 and 2008 -- that is, at least 2,400 data points (300 times four times two, focussing on the two major parties and ignoring the minor ones).

In addition to the positive (that is, what actually happened in the four competitive elections), we can also think about the circumstances under which the scion might be normatively better than other candidates.

For example, it is intuitively straightforward to argue that under most circumstances, the activist is qualitatively better for the polity and the society. But is there a circumstance when the activist is the “wrong” choice?

Activists of ideologically rigid parties could lead to a Manichean struggle. Once genuine elections are possible in Bangladesh, instead of the Sheikh League vs Zia Dal, will we be really better served by a Naxalite vs Taliban politics?

Admittedly, that is a rather extreme scenario, and perhaps not very likely in Bangladesh.

Let’s agree that in the Bangladeshi context, activists should be preferred. The question then is, with grassroots politics in abeyance for the past generation, whence the activists will come from? With the possible exception of Nurul Haq’s rights movement, there has been no sustained student politics, labour movement, or environmental or community movement. Local government mayors and chairmans have no authority.

When there isn’t any activist, who is better for the polity and society -- the scion, the celebrity, or the businessman?

Where electoral politics has deeper roots -- say, India -- perhaps the voters prefer dynasty scions because through trial and error, they have learnt that businessmen will only serve their interest, and the celebrities are often clueless, whereas the scions will do something for the community if only to maintain their family name.

Dear reader, you might be hearing about heirs and scions of this family or that in the coming year. Remember that the heirs and scions could be better than the alternatives.

First published in the Dhaka Tribune.

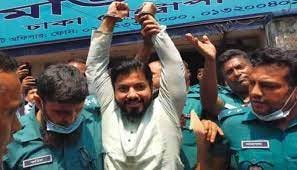

The photos are of people, from political families, who are working to restore politics in Bangladesh.

Further reading

14 rules for destroying a liberal democracy

Claire Berlinski, 6 October 2019

If the 20th century was the story of slow, uneven progress toward the victory of liberal democracy over other ideologies—communism, fascism, virulent nationalism—the 21st century is, so far, a story of the reverse.

Anne Applebaum, December 2021

How Vladimir Putin provokes—and complicates—the struggle against autocracy

As in the old cold war, ugly trade-offs are inevitable

Economist, 26 March 2022

The value of virtue: 7 reasons why Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s crisis leadership has been so effective

Self-explanatory

Suze Wilson and Toby Newstead, 29 April 2022

The strange case of the cricket match that helped fund Imran Khan’s political rise

Despite laws banning foreign funding of politics in Pakistan, documents show a money trail from Oxfordshire via the UAE to the coffers of Khan’s party

Simon Clark, 29 July 2022

Showdown at the Mansion Gates: How Sri Lankans Rose Up to Dethrone a Dynasty

An army of nuns, farmers and middle-class professionals felt a duty to save their virtually bankrupt nation. But their fight is far from over.

Mujib Mashal and Emily Schmall, 12 August 2022

Stories and Systems: Explanations of Regime Power in Bangladesh

Too much to summarise, and probably the must read of the links.

Shafiqur Rahman, 1 September 2022

This is a fascinating overview of a phenomenon too often glossed over as being evidence of corruption and nepotism.