There are very few books that can be described as a ‘life changing experience’, which how Dr Rumi Ahmed Khan, a medical professor, talks about Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal. “I warrant all my trainees read this”, he says. But it’s not only medical students and practitioners for whom reading this book might present an epiphany. And while written for an American audience, the book is not only relevant to the wider world, that relevance is only likely to increase for the global south over time.

“I learned about a lot of things in medical school, but mortality wasn’t one of them.” That is how Dr Gawande —a former surgeon and Harvard professor of public health —opens this 2014 book. He ends the first paragraph with “…the purpose of medical schooling was to teach how to save lives, not how to tend to their demise.” The rest of the book is about the implications and consequences of this prevailing attitude in a world where more and more people are living into their old age.

The first few of the book’s eight chapters explores different models of senior living. Gawande writes lyrically about multigenerational households, based on the lives of his Desi grandparents, of the days when it was taken for granted that families looked after their elders. But he is also unsentimental about the realities of the modern life that makes multigenerational families an unviable option in the west.

The economic realities of the 20th century west necessitated pensions, superannuation, welfare systems such as the American Social Security, but also retirement and nursing homes and aged care facilities. And Gawande shows that this is often a good thing for the elderly, who do not necessarily want to live with their children and follow their rules. Through anecdotes and stories of his family, friends and patients, backed up by his professional experience and expertise, and citations of research, he argues that like everyone else, the elderly too have a more fulfilled life when they feel they have a degree of autonomy.

The latter chapters try to show how the current medical and aged-care practises in the west fails the elderly when it comes to that vital sense of autonomy. “Our most cruel failure in how we treat the sick and the aged”, says Gawande, “is the failure to recognise that they have priorities beyond merely being safe and living longer.”

Two consequences have followed from this, Gawande demonstrates.

First, doctors focus too much on what a last-ditch operation might achieve, and too little on what economists call ‘the opportunity cost’ —that is, not just the out-of-pocket expense for the families, nor the health system resources that is spent on the surgery, but what alternative paths might have been pursued with that resources to ensure that the elderly “… have as good a life as possible all the way to the very end while coping with the fact that we are biological creatures, that we are flesh and blood and are going to have limitations as we go along."

For example, he cites research that shows that when patients with Stage 4 lung cancer are given the usual oncology care plus a palliative-care specialist who discusses the broader context and options —mortality, they tend to stop chemotherapy sooner, choose hospice earlier, less suffering at the end of life, and live 25 percent longer than patients with just the usual oncology care.

And the failure to properly value to the last phase of life, and particularly, the insistence on safety above all, has led to a dependence on care homes where, all too often, people are treated as a logistical problem, if not inconvenience. Gawande writes about the US, but the story is likely the same anywhere in the west. Even a high-end aged care facility would likely cater to the children of the elderly —your parents are safe here —not the elderly themselves. The residents are fed and kept safe and tidy, with the troublesome managed —that is how the typical aged-care facility sees its mission. A lack of respect for and empathy with the residents, unfortunately, follows far too often.

This is not a book about euthanasia. Gawande isn’t against the concept for terminally ill people in extreme pain. But he worries that reliance on assisted death is yet another distraction from what makes the end of life meaningful, not only for the dying, but also for those around them. He asks whether the Dutch have been slow to develop palliative care programs because “their system of assisted death may have reinforced beliefs that reducing suffering and improving lives through other means is not feasible when one becomes debilitated or seriously ill.”

This poignant book is a plea to the medical profession to shift away from simply fighting for longer life towards fighting for the things that make life meaningful. Dr Khan has been converted. But the book’s relevance does not stop with the professionals, because the issues of end-of-life is relevant to us all. And not just in the west. As Naeem Mohaiemen, an anthropologist and filmmaker, put it thus after his father’s passing:

We inhabit an unwieldy netherworld between faith and science. We routinely say “hayat jotodin” or “Allah took away his peyare banda,” and yet we race toward medical solutions that fight against the body’s natural cycle of decline. Anthropologist Rahnuma Ahmed recently reminded me that “in the old days,” people used to pass away at home, even in their sleep. Why doesn’t that peaceful departure happen any longer?

It is because at the first sign of troubled breathing, we rush loved ones to hospital. It is now inculcated in us that to do otherwise is neglect. Natural death is considered an aberration. We must all pass in a hospital, where protocols also demand an ICU, intubated experience in the final days.

As a human family, we have not developed any philosophy to face this new pharma-medical universe built out of an unwieldy collision of faith, science, hope, and refusal. We need collective thinking and writing, and the willingness to look outside of big pharma. For my fellow mourners, those who lost a loved one and struggle with thoughts of “if only” (earlier decision, different protocol, etc) -- perhaps we have to accept that the complex unravelling of the body at the end is also part of that hayat.

And occasional ‘dispatches’ (Facebook posts) from the rural and mofussil Bangladesh by Shafiqul Alam, the AFP’s bureau chief in the country, show that the issue is not limited to just the affluent anglophone class.

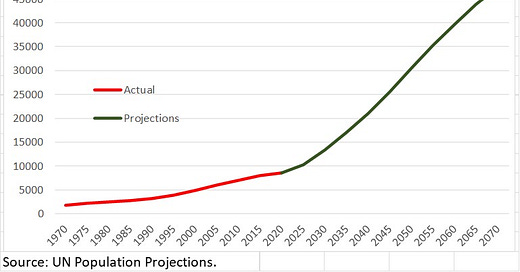

The story is simple, but not well appreciated. A few numbers (and the Chart below) might help. In 1970, there were less than 2 million East Pakistanis aged over 65. By 2020, the number would have more than quadrupled to be over 8 million. The UN projects more than another five-fold increase in the next half century —that is, the centennial anniversary of the Liberation War might be greeted with 47 million Bangladeshis aged 65 or more.

Meanwhile, we are also having far fewer babies. An East Pakistani woman in 1970 would have been expected to have nearly seven children over her life. A Bangladeshi woman today would be expected to have only two. The steady decline in the fertility rate has alleviated population pressure in our overcrowded delta. We have managed to not only avert famine and death, we have grown richer, and live better lives.

And we are living longer. Over the past half century, we have made tremendous improvements in life expectancy. An East Pakistani born in 1970 would have been expected to pass in 2017. A Bangladeshi born in 2019 would be expected to live till 2091.

But are our elderly living better?

The same economic forces that make multigenerational families unviable in the west are also at play in Bangladesh. Harkening to the tradition is not helpful for such tradition didn’t exist in a society where the average person is expected to live to their old age. A far better approach is to learn from the experiences of other societies that have experienced ageing.

Gawande writes in crisp, unsentimental prose. But it’s hard to not get teary reading about the places he visits offering a better way to manage life’s end: a Jewish retirement community on the same site as a school where the residents can act as tutors; a nursing home filled with pets for patients to care for; a sheltered-housing programme that commits itself to supporting all residents, no matter how complex their needs. Much of these is not fit for the global south. But in his current position as the Assistant Administrator of the USAID for Global Health, Dr Gawande might be expected to explore how some of the ideas can be adapted to the developing world.

In the 1980s, Bruce Springsteen had a hit song called ‘Glory Days’, about a group of middle‑aged folks revisiting their teenage years in the 1960s. As a society, not just in the west but also in the east, we need to reorient ourselves to believe that glory days are ahead of us. A freedom fighter of 1971 would be among the elderly today. A garments worker of today will retire tomorrow and be among the elderly. We must give them the confidence that they would have as good a life as possible all the way to the very end, no matter what comes. We must believe that each day lived is a glory day.

Beautiful