Bangladesh’s Demographic ‘Youth Bulge’

A decade old piece where I speculated about the 'big thing'

(This article was first published in March 2014).

Like a match box full of sticks —that’s how the Farmgate over bridge was once described to me. It was the early 1990s, when six or so million people lived in Dhaka, while Bangladesh’s population was around 110 million. I can’t think of any match box that, once full, can pack in a significant rise in the number of sticks, and yet, Bangladesh has somehow found room for extra people. In the two decades since my visiting friend saw the teeming multitudes of Farmgate, the country’s population has risen to 150 million, and depending on how one counts, Dhaka is home to 15 or more million people.

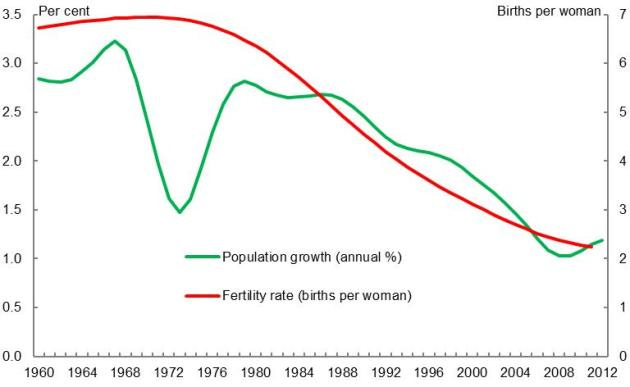

The headcount, however, does not quite capture the fact that Bangladesh is going through a demographic transition. A transition that is perhaps as remarkable as, and probably related to the Bangladesh paradox. As Chart 1 shows, over the past three decades, population growth has slowed significantly and the fertility rate (the number of children each woman bears on average) has declined markably. Given the fertility rate is already close to the replacement rate of around 2%, it is quite possible that population growth may well slow even further from current 1% a year.

Chart 1: Population Growth and Fertility Rate in Bangladesh.Source: World Bank World Development Indicator

Why has the population growth slowed and the fertility rate declined? Traditional theories of economic development explain demographic change this way: in poor countries, parents have lots of babies, not knowing how many (or if any) of the children will survive; as countries escape poverty, the odds of kids reaching adulthood rises, and parents gradually start having less babies, and focusing more on improving the health and education of the children; this substitution of children’s quantity for quality in turn accelerates economic development and sets off a virtuous cycle.

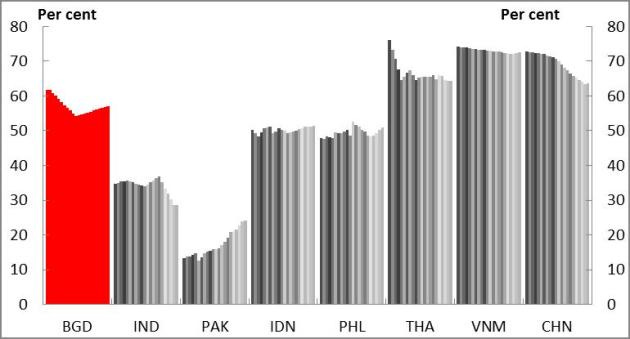

The traditional theories of economic development posit a negative relationship between economic development (usually measured by per capita GDP) and fertility rate. Chart 2 shows this relationship for a number of Asian countries, including Bangladesh, where the fertility rate has fallen recently. This is interesting because the fertility rate in Bangladesh has fallen at a lower stage of economic development, compared to neighbouring Asian countries. For example, India and Indonesia both have higher fertility rates than Bangladesh, even though those countries also have much higher per capita GDP than Bangladesh.

Chart 2: Fertility Rate and real GDP per capita in selected Asian countries (1980-2011).Source: World Bank World Development Indicator.

Bangladesh, however, has a fertility-GDP per capita profile that is quite similar to China and Vietnam. In those countries, strong government actions brought the fertility rate down. While successive Bangladeshi governments have encouraged family planning, nothing like China’s ‘one child policy’ was ever attempted in Bangladesh (and no one seriously expects Bangladeshi state machinery to enforce something like that even if the government contemplated it). Of course, Bangladesh has also had the NGO sector working hard on social issues such as family planning. Notwithstanding the NGO and government efforts, there is also another channel through which traditional economic theories of development and demographic change may explain what has been happening in Bangladesh. Compared with it’s South Asian neighbours, a lot more Bangladeshi women are active in the labour market. As Chart 3 shows, the female labour force participation rate in Bangladesh is higher than not just India and Pakistan, but also Indonesia and The Philippines —incidentally, China, Vietnam and Thailand have higher female labour force participation rates, as well as fertility rates compared to Bangladesh.

Chart 3: Female labour force participation in selected Asian countries (1990-2011).Source: World Bank World Development Indicator.

Where do all the Bangladeshi women work? Ready garments would, of course, be a major employer. But there are over 25 million economically active women (of over 15 years of age) in Bangladesh, and as big as it is, the RMG (Ready Made Garment) sector is not that big of an employer. Understanding female workforce participation is not just an interesting academic exercise, there are also important public policy implications, and the public policy issues are not just economic (narrowly defined) in nature, but venture into social policy sphere. Childcare, family relations, and the politically charged issue of female inheritance rights, all come into play when we start thinking about the ramifications of the demographic transition that Bangladesh has been undergoing.

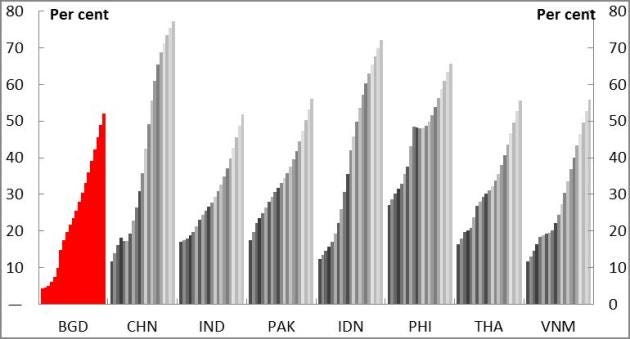

Public policy, and politics, becomes even more complicated once we realize that Bangladesh is also urbanizing rapidly (Chart 4). At the time of Partition, only 5% of Bangladeshis lived in towns and cities —again a lower proportion than our neighbours. By the middle of this century, we are likely to be as much an urban nation as most other Asian countries. This rapid urbanisation means long established social norms are likely to fray.

Chart 4: Urban population as %age of total (1950-2050).Source: World Bank World Development Indicator.

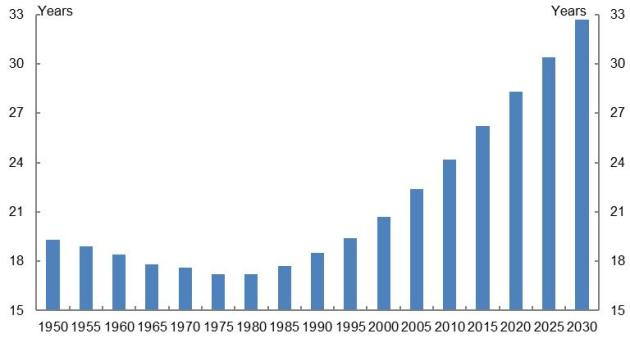

As a result of the demographic change, the median age of Bangladeshis is rising (Chart 5), and the country is in the midst of a ‘youth bulge’. In 2010, nearly a tenth of the population were (potentially) angry young men — male in their 20s. This proportion is going to only rise in the coming years. Imagine 15 million sexually repressed young men with little prospect in life. That could be tomorrow’s urban Bangladesh.

Chart 5: Median Age of Bangladeshis.Source: UN World Population Prospects.

The demographic structure of Bangladesh is similar to that of many Arab countries. Many European countries experienced a similar transition in the late 19th century or the first half of the 20th century, and many East Asian countries went through this in the past 50 years. There is a strong correlation between the youth bulge and major social upheavals — wars and revolutions, but also rapid economic progress.

Why should Bangladesh be an exception?

The striking feature about Bangladesh seems to me is not that it is potentially volatile, but that it’s actually so very stable. Yes, you read that right. Stable. When all is said and done about the sound and fury of 2013, is Bangladesh of 2014 all that different from that of 2012?

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t want millions of young people burn down the country in the name of some revolution, but it’s striking that they are not out there.

Or maybe they are just about to get there. Maybe we are on the cusp of something big. And if we can navigate that ‘big thing’ successfully, we should be able to reap the demographic dividend by 2030, when the population structure will be very conducive for a productive and prosperous society.

I am indebted to Mubashar Hasan for pushing me to write this back then, and digging it up after the Long July.

Success despite the odds: South Sudan and Bangladesh

Shantayan Devrajan, 14 Jan 2022

What’s driving the rich world’s falling fertility?

Stephen Bush, 22 Oct 2022

Tove K, 19 Jan 2023

The world’s peak population may be smaller than expected

The Economist, 5 April 2023

Why has fertility plummeted across East Asia?

Alice Evans, 19 Jan 2024

Arab countries anticipate another youth bulge

The Economist, 20 Nov 2024

Triumph and tragedy: trends in maternal mortality worldwide.

Adam Tooze, 24 Nov 2024

West Bengal is poorer than us and they have a lower force participation rate. They also have a much lower fertility rate (~1.3/1.4). Although this could be explained by the fact that West Bengalis are lazy and entitled. Women there don't work nor have kids.

Foreigners often label our development as a paradox, but what they see as contradictions are simply the nuanced ways we've navigated our national journey. Our social and economic landscape defies conventional Western frameworks, and that's precisely our strength.

Consider our economic model: we maintain a remarkably low tax-to-GDP ratio, with education and health services predominantly provided by private and non-profit sectors. Yet, our social indicators remain surprisingly robust. This isn't a weakness—it's our adaptive resilience.

We're a Muslim-majority nation with impressive female labor force participation, challenging simplistic narratives about religious conservatism. Our industrial policy, often critiqued as an elite-level private negotiation, has achieved moderate success that speaks to our pragmatic approach.

What outsiders call a paradox is fundamentally our way of life. People here take care of themselves and their communities. There's an intricate dance between state and business elites—a system of mutual understanding that has served us well.

Some media commentators demand increased tax-to-GDP ratios and more direct taxation. I argue we should resist such pressures. These advocates want to penalize work and success while subsidizing failure. Consumption-based taxation remains our most effective strategy, with gradual tariff reductions.

Critics might claim this stance supports inequality inherent in Anglo-American capitalism. But this is ahistorical. When the British first arrived in Bengal, they were stunned by our society's deep-rooted inequalities. Our class structures predate Western intervention—the notion of an imported egalitarian impulse is itself a Western construct.

This is why I'm a staunch supporter of federalism. We should double down on our cultural strengths rather than pretending Bangladesh can—or should—transform into a European-style social democracy. A federalized system would create more inter-state competition and provide enhanced opportunities for private sector negotiation.

Among South Asian nations, we've uniquely maintained our distinctive way of life. India, our ancestral cultural root, has repeatedly lost its way. They've been a second-rate version of successive global models: first the Soviet Union, then a European social democracy, and now attempting to imitate China—ironically using second-hand information filtered through American perspectives.

Our path isn't about emulation but adaptation. We're not a failed version of someone else's model—we're an evolved version of ourselves.