Fiscal policy settings became expansionary well before the pandemic and other global shocks. Budget deficits are not projected to narrow despite projections of record revenue mobilization. Considering the historical trend of revenue underperformance, either a wider budget deficit will have to be financed or the government will have to pare back expenditures. That is, the budget sets the government up for an unenviable choice.

The new Finance Minister has missed an opportunity to implement a better fiscal policy built around a more realistic revenue target and commensurate cuts to expenditure. Instead, the lack of credibility around the current fiscal stance and uncertainty over the future course corrections can exacerbate the current economic woes.

Budget deficit widened in the late 2010s and is set to remain so

Fiscal policy settings in Bangladesh became expansionary in the second half of the 2010s (Chart 1), well before the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical shocks such as wars in Europe and the Middle East.

Budget deficits used to be around 2.5-3 percent of GDP until 2016-17. Over the following two years, it widened to 4.7 percent of GDP. The latest projections are for deficits to remain over 4.3 percent of GDP into 2026-27.

A similar pattern is observed for the primary deficit, which abstracts from interest payments and is thus a better gauge of whether the fiscal stance is expansionary or contractionary. A widening primary deficit means the government is adding to demand in the economy. This can stimulate economic activities, but during times of high inflation it can further stoke prices. Primary deficit widened before the pandemic, and is set to remain wider than the experience of the first half of the 2010s.

It's not the revenue

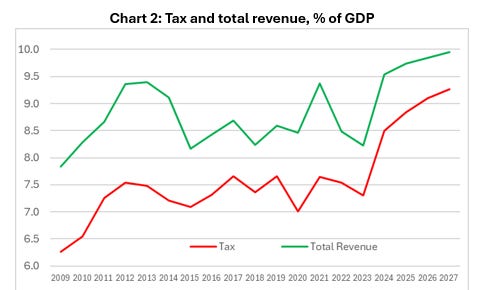

Budget deficit did not widen in the late 2010s because of declining revenue, as total revenue hovered around 8.5 percent of GDP and tax revenue around 7.5 percent of GDP (Chart 2). Further, total revenue and tax revenue are both projected to rise to record levels relative to GDP by 2026-27. That is, the persistently large budget deficit is not because of revenue.

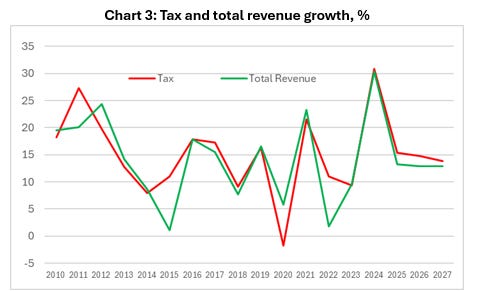

Achieving these record revenue targets will require strong growth in both total and tax revenue for three straight years, something Bangladesh hasn’t experienced in recent years (Chart 3). Achieving this will be difficult against the backdrop of an economy that is slowing because of rising interest rates and supply bottlenecks caused by import restrictions.

Bangladesh has a history of revenue underperformance —collections tend to be lower than the targets announced at Budget. If revenue collections fall short of the target, the government will have to either finance worse (than the already large) budget deficits or cut expenditures.

It was development expenditure then…

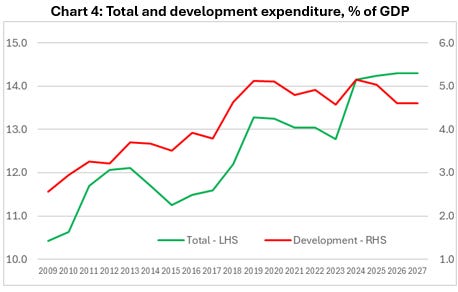

The widening budget deficit before the pandemic reflected a nearly 1.7 percent of GDP increase in total expenditure, of which 1.3 percentage points were in development expenditure (Chart 4).

However, development expenditure is not the main driver of the large budget deficits that are projected in the coming years. Development expenditure used to be around 3-4 percent of GDP in the first half of the 2010s, rising to around 5 percent of GDP in more recent years. The projections are for development expenditure to decline slightly relative to GDP in the years ahead.

… and subsidies, grants and transfers now

Subsidies, grants and transfers have risen recently and are expected to remain high relative to GDP (Chart 5). Expenditure on these items used to be 2.5-3 percent of GDP until 2020-21 but increased to 4 percent of GDP since then. In contrast, other expenditure items remain low relative to GDP by historical standards. Chart 6 presents the same information, but relative to total revenue collections.

That is, it is the expenditure on subsidies, grants, and transfer that is driving the persistently high budget deficits over the projection horizon.

If revenue collections fall short and the government were to cut expenditure, it would need to pare back either development expenditure or subsidies, grants and subsidies. This is a difficult choice. Cutting development expenditure can hurt future growth prospects. Subsidies, grants and transfer payments on the other hand reflect public policy rationale (for example supporting the vulnerable segments of the population) or political economy considerations (for example energy subsidies) that make it difficult to cut these expenditures.

Financing options are limited

Meanwhile, government’s financing options are limited. One option is to borrow from foreigners. Although interest rates on foreign debt are rising, they are still far lower than the interest rates on domestic debt (Chart 7).

External debt has become a relatively more important source of financing in recent years. However, external debt carries significant exchange rate risks as depreciation of the taka would mean a higher debt service burden.

The worsening budget deficits of the late 2010s were financed by National Savings Certificate sales to households. These instruments are relatively costly, and many of the earlier certificates are now maturing. The government has therefore increasingly opted for the third option of borrowing from domestic banks, which are now the main source of financing. Chart 8 shows the evolving financing mix over the years.

Against the backdrop of a weak banking system that is reeling from a large stock of non‑performing loans, government borrowing from the banking sector could crowd out private investment, hurting longer term growth potential of the economy. Genuine banking and capital market reform would allow for a deeper pool of financing source for the budget deficit as well options for households to channel their savings into productive investment. However, this does not appear to be on the cards.

As things stand, the fiscal policy stance is one of persistent deficit despite record high revenue projections. Further, the lack of credibility around these revenue projections mean there is huge uncertainty over whether, and how, the government will finance a worse budget deficit or which expenditures will be cut.

This uncertainty, in turn, will likely add to the current macroeconomic woes. In contrast, a more credible revenue forecast, coupled with a scaling back of expenditure, would have boosted confidence in the government’s ability to manage the macroeconomy.

Alas, that opportunity has been missed by Mr Abul Hassan Mahmood Ali.

Data sources

Fiscal indicators: Budget at a Glance from 2009-10 to 2024-25 and the Medium Term Macroeconomic Policy Statement from 2020-21 to 2024-25, all availed from the Ministry of Finance website.

Nominal GDP: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics National Accounts (earlier series spliced on to the latest release to create a longer time series).

Data available upon request.

A more formal version of this post appears here: Bangladesh Budget Review 2024.

Also: Mr Ali’s predecessors.

Further reading

David Coady, 1 Dec 2018

Value-Added Tax continues to expand

Ruud De Mooij, Artur Swistak, 1 March 2022

How Financing Can Boost Low-Income Countries’ Resilience to Shocks

Karmen Naidoo, Nelson Sobrinho, June 14, 2023

Debt clouds over the Middle East

Adnan Mazarei, 1 Sep 2023

Poor countries’ debt problems are keeping too many in destitution

Martin Wolf, 20 Dec 2023

Victoria Courmes, 14 Feb 2024

Tobias Adrian, Vitor Gaspar, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, March 28, 2024

Alissa Ashcroft, Karla Vasquez, Rhoda Weeks-Brown, April 2, 2024

Raising the tax-free ceiling in Bangladesh: A balancing act

Nasif Tanjim, 7 April 2024

Inheritance tax: A good idea, not so easy to implement

Ariful Hasan Shuvo, 12 May 2024

Govt to introduce first-ever prospective tax rates

Jasim Uddin, 5 June 2024

June 24, 2024

Currently tariffs make up 30-35% of our tax revenues. As part of LDC graduation, we would need to reduce tariffs across the board. I don't like taxes as much as the next guy but we're currently amongst the lowest taxed countries in the world. What taxes should we increase to finance the government after 2026-27? My preference would be property/land taxes and fiscal decentralisation.

> Genuine banking and capital market reform would allow for a deeper pool of financing source for the budget deficit as well options for households to channel their savings into productive investment. However, this does not appear to be on the cards.

Can you do into detail what some of the necessary banking and capital requirements involve? The first thing that comes to mind are the BSEC and ICB's interference in stock prices.